Development of The Silver Case began in earnest after the founding of Grasshopper Manufacture in March 1998. Suda entered a contract with ASCII, the company he tried to join before founding GhM, for publishing two games, the first of which was The Silver; because of this arrangement ASCII helped the then-six person team set up shop. Due to his frustration of being unable to create his own original IP while working at Human Entertainment, Suda decided to pour all of his ideas into this first title, which led to The Silver’s structure as a collage of different pieces of media: Animation, illustrations, live action footage, photographs, 3d modelling; these elements, often placed next to each other, went on to present the world of the 24th ward.

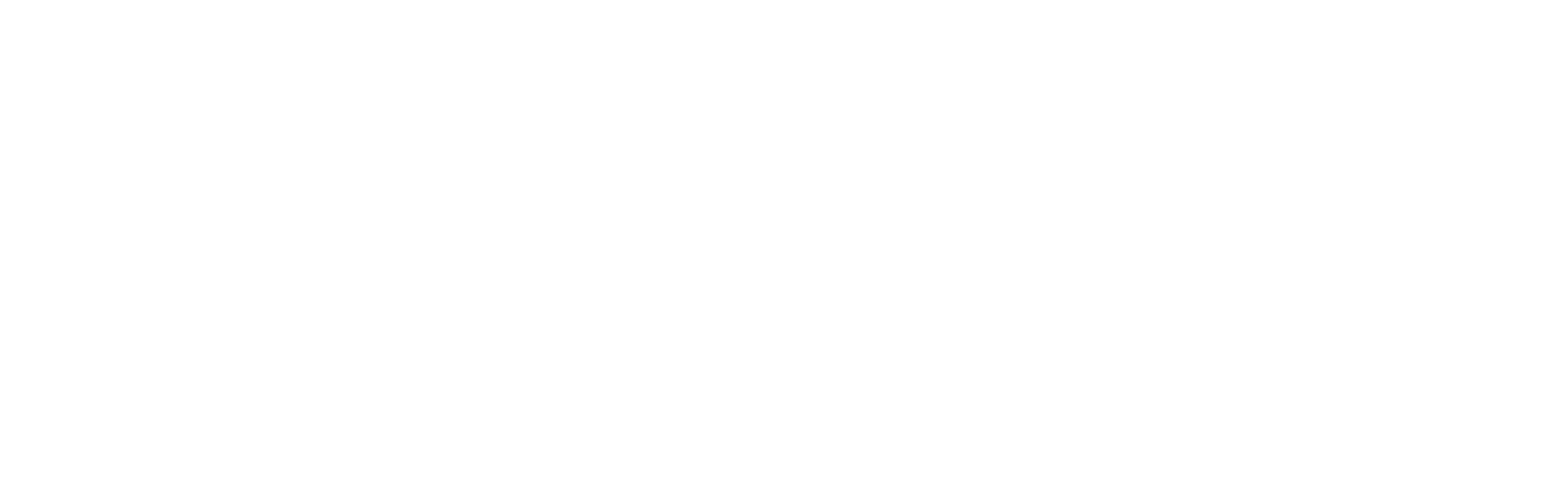

The mixed-media nature of the project and Suda’s own decision to create a new style of Adventure Game led to the creation of the Film Window, the game’s proprietary engine which allowed for text, images, videos and 3d models to be presented at the same time, adjacent to one another. It should be noted that since the beginning of his career, Suda was involved with development as early as data insertion, so the fact that his creative process began as early as codifying the game’s engine to facilitate its presentation should not be surprising. The inspiration for it came from the cinema of Godard, specifically the movie Nouvelle Vague, in itself a collection of vignettes, where imagery and text are presented at the same time to allow different perspectives to coalesce into a whole.

The system spearheaded by Suda would allow for several different pieces of media to be presented independently, with a “3D window” showing a polygonal rendering of the area where the scene takes place, a “movie window” showing animations, live action videos and 3D renderings, a “graphic window” showing static images, a “text window” which often displayed character dialogue but could change its resolution to display e-mails or written text, a “face window” displaying the portraits of whoever is talking at the moment, with text flashing around it to indicate their name, and lastly a “menu window”, displaying the actions the player could take to interact with the setting around him, along with the control system. The backgrounds themselves are also animated and change for each chapter.

As Suda stated in this episode of Creator’s File, the first obstacle he encountered as director and CEO was conveying his vision to his employees: as the game is essentially a collage of different types of media whose meaning is not immediately (or ever) clear without looking at it as a whole, lacking any context for his demands, his underlings would often misunderstand or criticize the composition of elements and scenes; moreover, he also had difficulties directing the shooting of the live action footage, as it would be outright incomprehensible when removed from the game’s context and, as videogames were not respected as a medium, camera operators would snap back at him, calling his demands “nonsensical”. In his words, this is when he developed the “ego” of a director, which I think refers to the ability of forcing his team to realize his vision despite their protests.

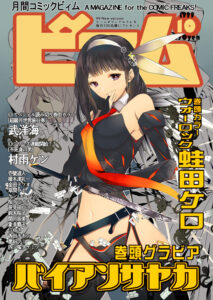

Several members of the Syndrome staff returned for The Silver Case: Akihiko Ishizaka, who followed Suda in his solo venture along with programmers Kawakami and Watanabe, returned as art director, while Takashi Miyamoto was once again hired as the character artist, for which he would discuss his designs with Suda directly. His work was complemented by several external artists: Masateru Ikeda (X) served as the artist for the “Placebo” story arc, Hirotake illustrated a fictional issue of Comic Beam Magazine issue advertising the idol Sayaka Baian, while a team of animators, including Shinichiro Ishikawa, Yuji Mukoyama and Konomi Noguchi, worked on the anime-style movies and original artwork for the Parade chapter and Masafumi Takada again provided the soundtrack.

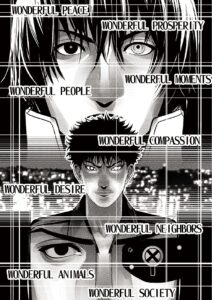

Narratively, the game is a hardboiled crime story: The Heinous Crimes Division, a division of the Central Police Department, has to investigate the resurgence of the legendary assassin Kamui Uehara in the 24th special ward, located in the ex-Tokyo area within the Kanto nation. As he explained in this Gameinformer interview, Suda’s decision to write this game as an analysis of crime and criminals was reached during development of Moonlight Syndrome, where his scenario had to undergo changes due to state-mandated censorship relating to the Kobe child murders, in which Shinichiro Azuma, under the alias of Seito Sakakibara, taunted the police force with the decapitated heads of his victims. This caused Suda to ponder on what exactly contributes to creating such an entity, the invisible intercourse between society and the individual which births a criminal. Suda’s father in law happened to be a policeman, which also provided an outlet for his research.

When I decided to make a new game, I thought about Moonlight Syndrome and The Silver Case was kind of a reaction to that. “What is crime? Who is a criminal? What causes crime? Who are bad people?” I decided to make a game using these themes. In this way, Moonlight Syndrome ended up being a much larger influence than my past work as an undertaker.

The “Transmitter” scenario, following the exploits of the Heinous Crimes Division, was complemented by the “Placebo” scenario, where journalist Tokio Morishima delves into the events of the story from a different perspective. Placebo was penned by Masahi Ooka, the freelance writer hired by Human to write Moonlight Syndrome: Truth Files. Suda ended up enjoying his book and called him to reprise the role of his journalistic counterpart for The Silver Case.

Initially, the Placebo scenario was even closer to the Truth Files, being envisioned as a collection of diary entries by Morishima; However, as development went on, more and more active narrative elements were introduced. Each of Placebo’s scenarios was penned as a response to the corresponding Transmitter one: In that sense, Ooka’s reporting style managed to shine, as Morishima and Ooka would both be trying to make sense of external events they engaged with as third parties, investigating the mystery of Suda’s writing.

The story itself picks up directly from the cliffhanger ending of Moonlight Syndrome, where one of its characters, driven mad, attacks the HCU detective Tetsugoro Kusabi as he’s driving home. The full moon shines on the characters through the entirety of the first chapter, aptly called “Lunatics” after a line in Moonlight’s エピローグ EPILOGUE. This reframes the events of Moonlight as an isolated incident within the larger context of The Silver Case: the urbanization of Hinashiro, a small town in Musashino, is now presented as part of the larger 24th ward project, which in turn exists within an exaggerated version of then modern day Japan where Tokyo, Ibaraki, Tochigi, Gunma, Saitama, Chiba, and Kanagawa have been absorbed into a larger, independent Kanto nation, which is however still governed from the Diet building.

In that same scenario, Suda also took the time to establish several plot points he was not allowed to include in Moonlight due to the previously mentioned state censorship, closing the first chapter in the Kill the Past saga definitively as it continues onto The Silver Case.

Before Lunatics even ends, the main character, a blank slate named by the player, is confronted with his first remnant psyche (残留思念 “lingering consciousness” in the official translation) and the purpose of the Heinous Criminal Unit is revealed, to eradicate the essence of crime itself, to exorcise the birth of crime. This is an evolution of a theme present in Moonlight Syndrome, where the “dark thought” (黒い念, though the 残留思念 spelling was used in promotional materials) that had seeped into the town of Hinashiro could not be exorcised by simply renovating the town; in エピローグ EPILOGUE, it is described as “tears washing away the blood”, an endless cycle. The HCU exists as a response to this, where its stated goal is to erase the “thought” of crime, its conceptualization.

As Lunatics closes on the imagery of the full moon, it’s clear that these two games are inextricably tied to each other, in both themes and story. Even though Moonlight Syndrome was rejected by the public and by the rest of the Twilight series, its spirit and world lived on in The Silver Case.

The game’s tagline, “Kill the Past”, which within the story serves as Kamui Uehara’s own motto, verbalizes a theme that was already present in Moonlight as well: moreover, it would go on to be repeated or played with in some way or another in all the games connected with The Silver Case, to the point where fans began using it to refer to the overall franchise.

The game was ultimately released by ASCII, in accordance to their contract, for PlayStation consoles in October of 1999. The game was also re-released the following year, sporting a new cover under the “ASCII Casual” label.

Unlike Moonlight Syndrome, The Silver only received a couple of extensions of its story: the first came in the form of a novel written by Naoko Korekata, released just a month after the game itself. Taking place between chapters 4 and 5 of Transmitter, the novel follows Sakura Natsume, daughter of Daigo. The second one, surprisingly, came in the form of a soundtrack CD for the game, released by the then-newly established web store ghmrecords in April of 2001. On the back of the disc, the track names have been arranged into a short story, further cementing the connections between the world of Moonlight and that of The Silver.

Also unlike Moonlight, the release history of The Silver did not end on the PlayStation: in 2007, a Nintendo DS version of the game was announced as a bundle with The 25th Ward, then a cellphone exclusive, following the re-release of Flower, Sun, and Rain on that same console. The game was actually developed, but due to a variety of reasons, including their inability to make use of the Nintendo DS dual screen set up and the sheer quantity of text that would need to be localized, the project was ultimately shelved in 2012.

In 2014, Suda was approached by Active Game Media through the intercession of Playism with a proposal to release The Silver Case on PC. AGM assuaged Suda’s fears in regards to localizing the Japanese text into English by implementing several layers of accuracy checks, with the translator in charge being James Mountain, who would ultimately join the company as community manager and localization expert.

As AGM handled development of the remaster, GhM would provide the original art assets for the game and supervise development, while the Film Window engine would be replicated in Unity 5 to facilitate future ports. This version of the game was released in October of 2016, seventeen years after the original.

While not described as a full blown remake, this version still made several changes to the original release: some of the artwork was re-drawn, Takada’s original soundtrack was remastered by Akira Yamaoka (who had joined Grasshopper Manufacture by then) and Erika Ito, the menus and user interface were re-done and the live action sequences involving Sayaka Baian were re-shot, replacing Hikaru Oki, who had played her in the original, with gravure idol Arisa Matsunaga. Moreover, the walking and text speed have been adjusted, according to Suda’s wishes.

Thankfully, most of these changes can be reverted or mixed and matched at the player’s leisure. There are some exceptions however: for one, the game sports new three-dimensional models, which are at times very similar, and other times radically different from the ones in the original release; secondly, the game now forces a 16:9 presentation, unlike the original 4:3, and lastly, the original artwork for Parade (which would have been drawn by either Yuji Mukoyama or Konomi Noguchi) was replaced with artwork by Takashi Miyamoto.

Upscaled versions of some pieces of the original artwork do exist within the game files, meaning that implementing it was originally considered, so the reason for its exclusion remains unknown. The origin of Miyamoto’s Parade artwork is also uncertain: it had already made an appearance in the 2007 soundtrack CD The Silver #02 + Parade, meaning it is possible that it was produced for the original release and then left on the cutting room floor.

This re-release also came bundled with a short comic further connecting the world of The Silver Case with that of Moonlight Syndrome, which was written by Suda himself and drawn by Syuji Takeya, who would also serve as the artist for Kurayami Dance and Red, Blue and Green, two more Suda-authored mangas.

The later PlayStation 4 release of The Silver Case, which came out in April of the following year, included two brand-new chapters authored specifically for it, which were later implemented in the PC version through a patch. Whiteout Prologue, written by Suda with Miyamoto providing the art, followed the Transmitter arc by introducing the world and characters of The 25th Ward, while YAMI, written by Ooka with Ikeda also returning as the artist, follows the Placebo arc and strengthens the connection between this game and Flower, Sun, and Rain.

All this to say that even in 2017, twenty years after the release of Moonlight Syndrome, Suda was still interested in deepening the connection between his works and preserving those titles as best as he could. The Silver Case was later bundled with The 25th Ward, its sequel, for subsequent PlayStation 4 and Nintendo Switch re-releases under the label “The Silver 2425”.