The original No More Heroes marked the end of the Classic Era of Grasshopper Manufacture, the main focus of this website, and the beginning of what we arbitrarily refer to as the Blondes Era, in which Suda’s newfound obsession with blondes also coincided with a period of rapid expansion and artistic compromise for the company.

On one hand, most of the original key figures (Ishizaka, Takada, Miyamoto, Sasaki) that helped shape the company were still part of No More Heroes’ development team, with Suda serving as both director and writer; on the other hand, the game introduced Grasshopper’s first three blondes with Sylvia Christel, Bad Girl and Jeane, some light sci-fi elements with the Beam Katanas and, most importantly, a company mascot in the form of Travis Touchdown, three elements that would soon become staples of Grasshopper Manufacture.

However, before we delve into the Blondes Era proper, there was another title GhM developed in tandem with No More Heroes as part of the Zero series, known as Fatal Frame in the United States and Project Zero in Europe.

Zero is a Japanese horror series produced by Tecmo in which the player, usually thrust into the role of a young girl, is assaulted by ghosts which must be exorcised by using the Camera Obscura, a photographic camera built by Dr. Kunihiko Asou to pacify wandering spirits.

The first title in the series was released on PlayStation 2 in 2001, and was followed by two sequels on the same console, “Crimson Butterfly” in 2003 and “Call of the Tatoo” (known as “The Tormented” in the west) in 2005. The first two titles also received expanded ports on Xbox.

Zero’s creator, Makoto Shibata, became acquainted with Suda during the 2005 E3 conference through the intercession of a Famitsu editor, and the two bonded over the mutual appreciation of each other’s games. As you already know from going to church every Sunday, Suda is notoriously afraid of ghosts, an interesting character quirk for a man who worked as a funeral director. It was actually his wife, a devout horror fan, who forced him to get over his phobia and get into the series. Meanwhile, Shibata was very impressed by the depiction of ghosts in killer7, how they’d show up in the middle of the levels, unaware of their own deaths, only to make mundane complaints.

A few years later, an idea surfaced for a fourth Zero game, this time produced by Nintendo for their Wii console; series co-creator and producer, Keisuke Kikuchi, knew that Grasshopper Manufacture had experience with the Nintendo Gamecube hardware, in itself not dissimilar from its successor. Due to this and Shibata’s acquaintance with Suda, GhM was ultimately contracted to co-develop the game.

Suda initially rejected this proposal, but was talked into it at the condition that Shibata would also serve as co-director and co-writer, 51’s way of ensuring that the game would stay true to its roots.

A third director also came into the picture, Toru Osawa, a Nintendo employee as the company was partially funding the title as a Wii exclusive. The three directors would clash at times, delaying development, but the game ultimately came together thanks to Keisuke Kikuchi restoring order as producer.

The game was originally conceptualized as a collection of short stories with no connection to the main series; It was soon decided to instead focus on a singular plotline, although the finished product is still independent from the rest of the Zero franchise.

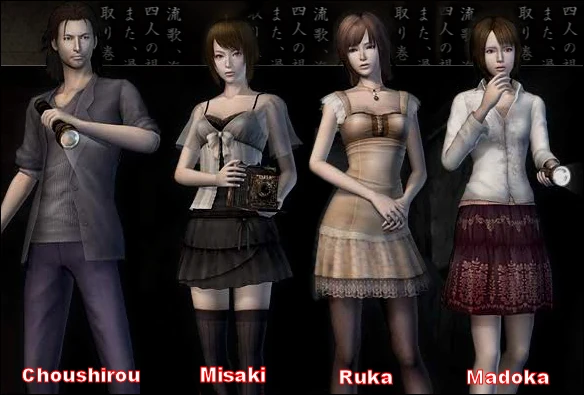

Zero: Tsukihami no Kamen begins in 1970, when five girls are abducted from a sanatorium on Rougetsu Island (south of Honshu) by alleged serial killer Yo Haibara. The girls are found unscathed in a lonely cave by detective Choshiro Kirishima, who was investigating Haibara. However, they have no memory of the events that transpired.

The five girls then leave the island. Two years later, the entire population of Rougetsu is wiped out by a mysterious catastrophe. In 1978, two of the girls, lured back by their forgotten past, die under unknown circumstances, and two more, Misaki Aso and Madoka Tsukimori, leave for the island to find out what happened to them. Madoka is quickly killed by ghosts, while Misaki’s fate is left hanging.

That’s when the two main playable characters, the previously mentioned detective Choshiro Kirishima and the fifth surviving girl Ruka Minazuki, also return to the island. Ruka fights her way through the wandering spirits using the Camera Obscura, while Choshiro has to fend them off with a moonlight-powered flashlight. Through the course of their investigation, they eventually uncover the connection between the girls’ memory loss, the death of all the island’s inhabitants, and a disease dubbed Moonlight Syndrome.

(It should be noted that, while the name of the disease, 月幽病, can indeed be translated as Moonlight Syndrome, it bears no connection with the 1997 game of the same name, which was instead spelled in English using katakana as ムーンライトシンドローム.)

Some of Suda’s hallmarks are apparent even in this short synopsis, namely the focus on lost memories and the full moon imagery. However, his contribution to the scenario was actually quite minimal.

The original arrangement saw Shibata as the main writer for the girls’ side of the game, while Suda would provide the script for Choshiro Kirishima’s sections. After receiving Suda’s script, however, Shibata was shocked by the amount of gore and violence and immediately tore it to shreds, going as far as to delete Suda’s email and purge it from his hard drive. After realizing how idiotic it was to contract an outrageous writer specifically because of his outrageous writing only to get outraged at his writing, he then tried to reconstruct his script by memory, though excising the most violent aspects. Shibata was ashamed of the profound retardation of his actions, but Suda reassured him that he did, in fact, manage to convey Choshiro’s scenario as he originally intended.

From this exchange it is clear to me that Suda was trying to channel his experience with Moonlight Syndrome, which was intended to be far more violent than how it ended up being, featuring heads exploding and on-screen decapitations. Another interesting tie-in with Moonlight is what Shibata described as the “Zero Region”. Quoting from the Suda51 Official Complete Book:

The meetings with Mr. Suda about the game were always surprising, but those things are too numerous to mention, so let me tell you about just one. One of the themes of this game for me was visualizing the scenery that lies beyond our memories. At the end of the game I wanted to show the scenery of the moment right before your consciousness is born, at the place where nostalgia for death and the consciousness of life are born, something which everyone remembers somewhere. The visions I saw and remembered of that landscape, known as the “zero region” in the game, were a chaotic, milky-white melding of light and dark, abstract and difficult to express. I knew it was probably impossible, but even if it was only as a mysterious vision at the end, I wanted to share what I saw with the players. Mr. Suda said of the place: “If a place like that existed, I’d like it to be something like ‘paradise’,” and his words influenced me strongly in realizing that final scene. It may be a very personal and trivial thing, but I wanted to talk about it somewhere.

This is, of course, starkly reminiscent of the depiction of the “edge of the world” in Moonlight Syndrome, a memory that becomes a place, which is, indeed, often associated with the concept of “Paradise” in Suda’s work.

Zero: Tsukihami no Kamen ended up being released in July of 2008, its release month being chosen specifically to tie into the Japanese tradition of sharing ghost stories and rumors around July. Much like No More Heroes, the game was entirely built around use of the Wiimote, in order to facilitate player immersion, though with markedly different aims.

While the notoriously imprecise motion controls were used sparingly in No More Heroes, with most of it adopting a simple gameplay style and control scheme to account for them, Tsukihami no Kamen utilized them for the entirety of its core combat, which ends up feeling unfair or unbalanced because of it, even when using the Wiimotion plus periphery supposedly meant to improve precision. Moreover, the game was quite buggy, with several crashes happening at key points and certain optional objectives being impossible to achieve due to errors in programming.

Due to these and other reasons, initial plans to localize the game were scrapped. A fan translation was produced by a three-person team and released in January of 2010. The game would not see an official localization until the release of its remastered version in March of 2023, which featured bugs fixes, some revamped textures and a new control scheme based around modern controllers. The remaster, localized as Fatal Frame: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse in the US (while retaining its Project Zero title in Europe), was released on Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4 and 5, Xbox One and Series X, and Personal Computers. Its limited edition also came bundled with a book called “Rogetsu Isle Reminiscences”, which included a new short story and other extensions of the world of Zero 4.

As development on Tsukihami no Kamen wrapped up, Suda finally presented a finished draft for his personal project, Kurayami, at Grasshopper’s tenth anniversary party. Since Kurayami’s development devolved into a 3-years long bureaucratic nightmare, as detailed on its page, he would not be as involved with Grasshopper’s next release, No More Heroes 2: Desperate Struggle.

The idea to produce a No More Heroes sequel was originally verbalized by Suda himself in March of 2008, right after the European release of the original, in an interview with Computer and Videogames. The stated condition for the existence of No More Heroes 2 was that sales might satisfy the publishers, Marvelous for Japan, Ubisoft for the United States and Rising Star for Europe.

Sales were indeed satisfactory, at least for Marvelous and Rising Star. Therefore, No More Heroes 2 became the first original outing in Grasshopper’s catalog to be pushed forward due to financial expectations, rather than out of arbitrary artistic inspiration. No More Heroes was meant to be a one-off game, its subversive ending intended to stand for itself, rather than lead into a sequel.

The game was originally announced in October of 2008, during Tokyo Game Show. Marvelous and Rising Star returned as publishers for the Japanese and European market respectively, while Ubisoft was initially replaced with XSEED for North America, though they would inexplicably announce their return during the 2009 E3 conference.

As I already established, Suda was busy bickering with EA over the direction of Kurayami during development of No More Heroes 2; therefore, unlike the original, he would not direct the game. Directorial duties fell instead on Nobutaka Ichiki, who had joined the company as Planner during development of GhM’s Samurai Champloo game and had also served as co-director for the original No More Heroes and Event Designer for Tsukihami no Kamen. Satoshi Kawakami still served as programmer, but this would be his final game under that role: afterwards, he was promoted to a managerial position and mostly handled contract negotiations.

Suda would provide a script for the game, but as opposed to his earlier outings, the script was written after characters designs by returning artist Yusuke Kozaki were already finalized, and mostly served the purpose of finding excuses for the main character to be involved in boss fights; in other words, a pretty standard videogame affair.

51 was not the only notable absentee; Original composer Masafumi Takada left the company in November of 2008, shortly after the announcement of No More Heroes 2, in order to found his own studio, Sound Prestige. Similarly, art director Akihiko Ishizaka had, by then, left GhM to join Spike, another company that was originally founded by ex-Human employees that was, at the time, about to go through a merger with Chunsoft.

The services of long-time collaborators Takashi Miyamoto and Masahi Ooka were likewise not requested for this title, and this would be the last time Eisin Sasaki took part in active development, with his graphic design being relegated to promotional trailers and merchandise for Shadows of the Damned, Lollipop Chainsaw and Killer is Dead.

The end result is a game that ends up feeling markedly different from GhM’s previous output; up until that point, setting aside contract jobs, the company’s catalog had been a collection of wildly different and unique titles that aimed to build new game systems; No More Heroes 2 is, for all intents and purposes, a videogame like many others, built to be a product first and foremost.

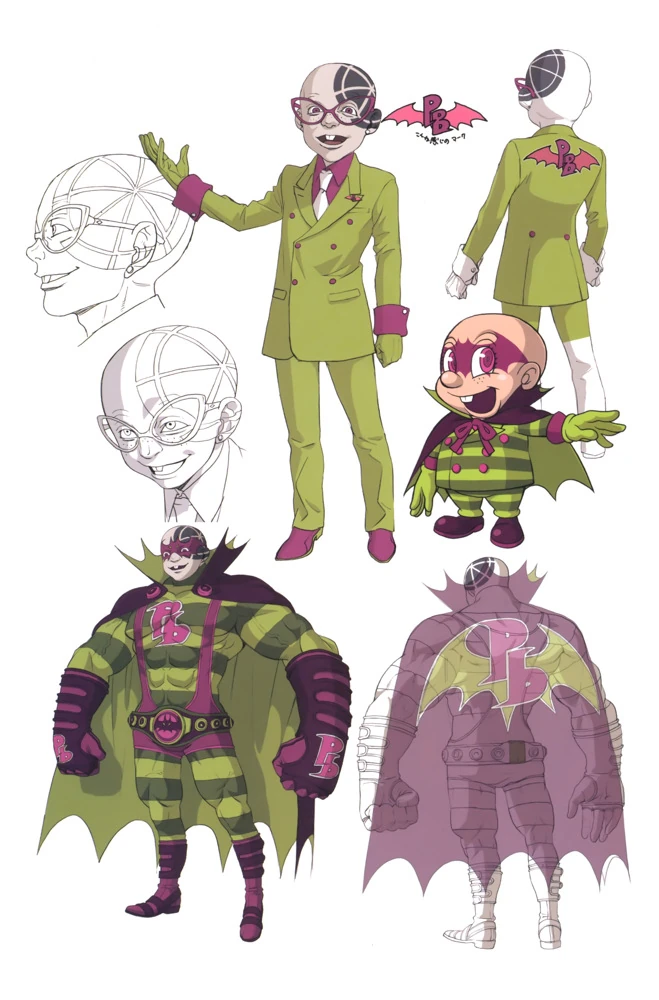

Desperate Struggle tells the story of Travis’ quest for revenge against Jasper Bat, CEO of the Pizza Bat (formerly Butt) conglomerate, who used his mafia contacts to kill Bishop, Travis’ best friend and owner of the video store, as revenge for Travis killing his family members in a few side missions in the original No More Heroes. Jasper Ass just so happens to be the number one assassin in the UAA, so Travis is once again approached by Sylvia to join the ranks and fight his way to number one to enact his revenge.

We’ve already established how well the character of Travis Touchdown captured the platonic ideal of a 2007 Burbank /b/tard thanks to Suda’s unmatched ability to channel the current zeitgeist. However, unlike characters depicted in previous Grasshopper games, it just so happened that members of that specific subculture were also avid gamers.

So it came to be that the existing fanbase for the No More Heroes games resembled Travis enough to promote him to the role of company mascot for the foreseeable future.

The specific zeitgeist the game happened to tap into, perhaps unintentionally, was the late 2000s, early 2010s trend of nerdsploitation. By then, being a “nerd” or a “geek” had become a commercialized fashion identity, in itself openly self-referential and derivative of existing pop media, be it comicbooks, sci-fi and videogames.

This subculture was encapsulated by the TV show The Big Bang Theory and, most relevantly to our one-sided conversation where you sit down in silence and I complain to you about shit from 20 years ago, the comicbook Scott Pilgrim, which was also adapted into a movie by Edgar Wright in July of 2010.

What follows is a completely unbiased, canonically accurate and formally approved summary of its story.

Scott Pilgrim is a Canadian bass player and proto-incel who exists in a world where the border between reality and pop culture is thin, if not immaterial.

The story sees the 22yo, currently involved in a sinful relationship with a 17yo girl, fall head over heels for the mysterious suicide girl Ramona Flowers.

Unfortunately for Scott, Ramona was right in the middle of her tumblr-mandated cock-carousel tour, an essential stepping stone in the life of every woman sporting purple hair before ultimately growing fat and ugly and marrying a wealthy yet castrated man sporting a Norwood balding pattern. Infidelity, divorce and murder sometimes follow.

The two-timing manwhore Scott, irate that his new girlfriend had been sucking dick before meeting him, proceeds to go on a murder spree, snuffing out the lives of her seven evil exs for the sin of challenging his nu-manhood. The grim violence of his sociopathic bloodbath is, however, toned down by the fact that Scott’s sexual rivals explode into bags of coins, excising any depiction of violence.

Scott Pilgrim’s real power is, of course, that of being a geek, the kind who would proudly purchase a pre-faded Zelda t-shirt from Target despite showing no actual interest in the property itself. As such, his thirst for blood is not only justified, but also made righteous through the invocation of a memetic Egregore in the shape of a stereotypical high school jock who is also a republican.

Scott’s murders are always presented under the guise of videogame logic, with mechanics such as level ups, extra lives and loot drops being used liberally through the story, while omitting more realistic details such as the grieving families that would naturally be left in tears by the deaths of so many young men and women (spoiler: Ramona is bisexual) for the sin of being sexually adventurous with the wrong girl.

How does the story continue? We’ll never know, as I have never read Scott Pilgrim in my life. I have heard rumors that Scott eventually achieves fame by starting a social movement to improve ethics in gaming journalism, but these claims have been disputed.

QUOTE OF ENLIGHTENMENT:

YES. I’m inspired. I found out the real meaning behind green watermelons, which is a matter that deserves much more attention than that given till now. People just don’t understand how smart and developped organisms watermelons really are. The Watermelon is an overlooked gem.

Yes, they are green. But not any kind of green you find in cucumbers or any other vegetable of that ilk.

– Kitano Smith

What’s important for us is that the detachment from the grotesque reality of his actions achieved by Scott by embracing his escapist delusions is remarkably similar to that achieved by Travis Touchdown.

This connection is not unknown to Suda; Brian Lee O’Malley, the author of Scott Pilgrim, was a fan of No More Heroes and even went as far as to sneak Travis Touchdown in a panel of the sixth volume of the series, released shortly after Desperate Struggle, and Suda himself mentioned being a fan of the series and its author after the release of the movie.

Despite focusing in on the same subculture, however, it should be noted that the original No More Heroes did so from an outside perspective; Travis’ Chunibyo escapism was looked at through the eyes of an outsider and his character traits were depicted in the game accordingly. Chuni-like behavior was an integral part of the “geek” lifestyle. When trying to market a game to that audience, it’s clear that the lens had to be turned inwards, leading to the wild tonal shift of Desperate Struggle.

In a lot less words, while No More Heroes was a game about an antisocial otaku, Desperate Struggle became a power fantasy for antisocial otakus. As such, elements that were included in the original game due to Travis’ interest in them, ended up engulfing the entire setting, turning it wildly more farcical and exaggerated.

For example, a specific scenario sees Travis fighting a team of 25 cheerleaders piloting a mech with his own giant robot, something that he could only dream of by engulfing himself in media in the original. Through the course of the game he will fight against monsters, ghosts, and other supernatural manifestations; for all intents and purposes, the entirety of Santa Destroy has been swallowed and absorbed by Travis’ escapist delusions.

This is likely why that the fourth-wall breaking ending of No More Heroes was completely ignored in the sequel; at the end of the original game, the UAA is revealed as a non-existing organization, a scam set up by Sylvia to have lowlifes and killers part with their money as she bribed her way into high society.

Despite this revelation, Travis still elects to go through the final ranked fight: there, he is met by a man claiming to be his father, who is instantly killed by Travis’ half-sister ex-girlfriend, who reveals that she has killed Travis’ real family in the past (an episode which he has erased from his memory and can only vaguely remember in a drunken stupor) out of revenge for being raped and abused by Travis’ (and her own) father. This backstory is quite literally fast-forwarded during the scene.

Sylvia had set up the encounter specifically to allow him to get revenge, to overcome his trauma and KILL THE PAST; after that is accomplished, he is challenged by his double-secret twin brother, who also happens to be Sylvia’s husband. By this point, the reality of the game breaks down completely, with the two characters openly discussing how convoluted the plot has become, and ultimately electing to fight to the death in order to escape the game’s reality through the exit called Paradise.

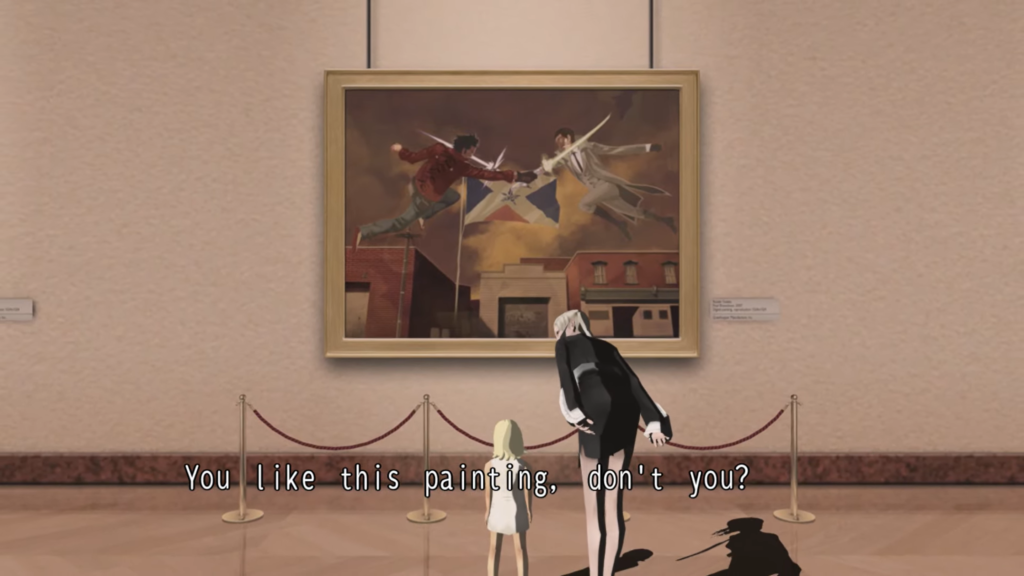

In a post-credits scene, Sylvia is shown walking her daughter (which she presumably had with Travis, as the first game implied they had sexual relations, though this point is also disputed in the sequel) through a museum, revealing that she named her Jeane, after Travis’ half-sister and ex-girlfriend who, in case you forgot, was also her sister-in-law through her being Henry’s (Travis’ twin brother) half-sister.

I don’t think it’s a stretch to assume that such an absurd series of events was intended to poke fun at the general tropes of videogame storytelling, and on a deeper level to signify Travis’ willingness to break out of his trauma-induced delusions and join the real world. This is likely why most of these revelations, outside of Henry’s role as Travis’ twin brother, are completely ignored or contradicted in the sequel, where the UAA is treated as a legitimate organization and the absurdity of its plot is never acknowledged.

The morality of Travis’ actions is also framed in a much more pandering way; as an audience surrogate, having him be the initiator of violence, occasionally killing civilians for money as he did in the original, would be unacceptable.

Therefore, a frankly bizarre balance is achieved by first having Travis casually accepting the task of killing 50 people under the promise of a blowjob, only to then provide a righteous motivation for him to engage in manslaughter.

At the same time, while the original took time to establish that Travis was not in any way morally superior to his rivals, every one of Travis’ enemies in Desperate Struggle is either a monster in need of extermination, an evil villain whose death is inherently righteous, or a devout follower which longs for nothing more than to die at Travis’ hands. This is compounded upon by the fact that the hitman assignments of the original have been completely excised, replaced instead by “revenge” missions in which Travis takes down the mafia goons that killed Bishop.

Framing the player character as a morally righteous God in order to facilitate juvenile power fantasies within the context of a game was nothing new even back then; it is, in fact, standard procedure in videogame writing. It is only a novelty in the context of Grasshopper’s previous work which was, with the exception of Contact, mainly aimed at adults.

Travis had, for all intents and purposes, metamorphosed into “One More Hero”, one that enacts righteous justice and makes every woman fall at his feet. In doing so, Desperate Struggle retroactively destroys the context of the original game, by justifying and celebrating Travis Touchdown’s escapist delusion to pander to an audience which, just as he did, decided to drown out reality under an endless barrage of juvenile fantasies.

The fact that the actions of a protagonist must only be morally righteous in the context of a Manichean good vs. evil struggle has since then been popularized in all forms of pop media in the anglosphere, likely helped by the extreme rise in popularity of superhero media during the 2010s, to the point of having drowned out the existence of unidealistic protagonists as a concept. The idea being that any sort of story can only be a morality tale, in which characters who commit foul actions must be punished accordingly by the narration in order to imbibe a lesson into the viewer.

To see an example of this one needs to look no further than how the game is perceived in the year of our lord 2023, thirteen years after its initial release: Twitter users were completely scandalized to discover a scene in which Travis is complicit in the killing of two black women, as the protagonist’s morals do not, in this case, align with those of the user, which is now understood as a mistake in the writing. (Specifically, the implication is that Travis, and by extension the game, is racist. As the killing of twenty-five cheerleaders and several civilians in the previous game’s hitman missions did not elicit any reaction, meaning that manslaughter is not the issue.)

Of course, this mostly applies to the anglophone world, as most real countries are still allowed to produce media aimed at adults that is unafraid to delve into darker and more controversial aspects of the human experience. As the game was produced in Japan, this may seem unimportant, but I will remind you that sales of the original No More Heroes were disappointing at best in its motherland, meaning the sequel would necessarily have to cater to a foreign audience. More importantly, Japan’s entertainment industry has become more and more reliant on foreign costumers as years have gone by, as ballooning budgets necessarily require a larger audience to turn a profit.

How much of this tonal shift was because of Suda’s script? We are actually in a very fortunate position in critiquing this game in the context of Suda’s career, as the production script somehow leaked during development. The differences from the finished product are mostly minor, but at the same time pretty significant:

Ironically, the scene that caused so much uproar among submentals actually saw the rival assassin, Nathan Copeland, killing the two black women in cold blood. Their death is more gruesome, but if they went with this scene they could have saved themselves some headaches in the coming decades.

Nathan throws the two girls.

Unable to avoid the girls, Travis’s field of vision is obstructed.

Nathan seizes the moment and jumps.

A drill comes out of a radio-cassette player as he impales Travis along with the girls.

The girls shriek and after a desperate effort, die.

The optional revenge missions were originally meant to include terrorist attacks on various institutions; one very understated aspect of the game is that the Pizza Bat conglomerate has effectively gentrified Santa Destroy by taking control of all of its infrastructure, which is only ever hinted at in the prequel short film, and Travis would take back control by bombing office buildings and even hospitals.

Killing mission

Objective is to take over all Pizza Bat controlled areas.

Along the way are missions where player takes revenge on the five men who killed Bishop.

Criminal activity such as raiding hospitals and bombing offices too.

Missions vary depending on actions taken during battles.

Total of 20 missions. One story thread will link all the missions.

While it may seem minor, this would have framed the game much differently than just a straightforward tale of righteous revenge: the ties between urbanization and the encroaching of international capital on sovereign soil, which in turn lead to the homogenization of culture, has been a recurring theme in Suda’s work ever since his second writing job, Moonlight Syndrome.

It is also interesting to note that similar conglomerates played a major part in the cultural shift from “urban” (street-level) to “nerdy” (pie in the sky). It is possible that this was an intended theme that ended up being scrapped during development, as rivalries within the game are often framed along the lines of arbitrary fashion groups (“emo”, “goth”, “grunge” and so on) based around musical trends.

The final boss, Jasper Bat, as noted by literary critic Jonathan Holmes, is designed as a mesh between the american superhero icon Batman and his rival, the Joker. Despite Suda’s lesser involvement in the game, he has been namedropping american superheroes since at least Moonlight Syndrome, with Batman being specifically referenced in Killer is Dead (the short story, not the game), so it is unlikely that he was unaware of this connection. Moreover, Jasper Bat also happens to turn into a giant corporate balloon at the end, a metaphor that, while obvious, lacks some much needed context with the removal of the gentrification motif.

A third change which I personally found interesting revolves around a fan-favorite scene that utterly bewildered me: in it, Travis Touchdown, after killing the assassin Alice Twilight, goes on a seemingly random tirade about the rights of imaginary characters.

Now, I am going to be completely honest and admit that I had no fucking clue what the game was trying to say here, as in my experience living in the real world, anime characters are not, in fact, alive.

There are fringe opinions held by internet personalities such as Linkara or Chris Chan (who was, at one point, arrested for raping his demented mother) who honest-to-God believe that fictional characters exist in an alternate universe that occasionally intersects with ours, but those are absurd ideas, not something that an educated man would entertain.

Stunningly, the leaked script actually provided an answer for me: the scene immediately preceding it was altered, removing some much needed context. In the finished game, Alice Twilight praises Travis for managing to get out of the game, for walking away from a life of killing. In the original script, she instead praises Travis for being a superstar assassin, one who is able to live in the spotlight rather than hiding in shadows, setting an example which makes other people eager to fight.

ALICE:

I’ve been thinking this awhile…

As these ranking fights become an official spectator sport…

Tell me… why do all these assassins join if they’re going to end up killing each other anyway?

TRAVIS:

Does it really matter why?

ALICE:

At least to me, it’s rather important.

Living out their lives in the shadows,

if given a chance to live in the day light,

no assassin would pass it by.

TRAVIS:

You think so…

Well I got no clue what you’re talkin’ about.

ALICE:

I’m saying, everybody wants to fight you.

Don’t you get it?

TRAVIS:

Get what?

ALICE:

The one that found the daylight…

Is you, Travis Touchdown.

The idea that Travis is a superstar is somewhat hinted at in the finished game, but it is mostly brought up in the prequel movie, with the idea being that, by taking part in the ranking fights in the original game, he (inadvertently) ended up cleaning up Santa Destroy and becoming a sort of folk hero. With that context, his line about protecting the rights of imaginary characters gains a completely different meaning: what he’s actually trying to say is that these assassin fights may seem no different from any other entertainment to the spectators (movies, mangas and so on) but they’re out there bleeding and dying in the real world.

His line about tearing down the UAA, which is a plot point never brought up again in the game after that one sentence, is also slightly different in the script. The implication being that Travis will choose to lay down his weapon and stop fighting after he takes his revenge on Jasper, putting an end to the endless slaughter of the UAA (as he would stop serving as an example of a superstar assassin), with Sylvia rebutting that someone else will simply take his place, meaning the killing will never end.

TRAVIS:

The next match will be the end of the UAA.

SYLVIA:

Are you done bitching?

You could never shut down the UAA.

Ranked fights will continue regardless…

Even if you become number 1, another hero will be born.

These lines are actually unaltered in the Japanese version, meaning that the confusion must have been originated by the localization team, rather than this being an intended change from the director; unlike the original No More Heroes, for which the translation was handled by Japanese natives at Marvelous with help from Katalyst Lab, this time Ubisoft provided a Californian localization manager, Catalina Quijano, which translated the game in conjunction with the Enzyme Testing Lab team. Katalyst Lab’s own Tad Horie, who served as supervisor for the original No More Heroes, this time directed the voice acting process instead of Kris Zimmerman.

Two other alterations exist in the script: for one, the game was meant to include an open world much like the original title. This was scrapped during development and replaced with a menu in which the player can select the various activities. Secondly, a secret boss fight with Shinobu Jacobs was originally meant to be implemented, though no story content relating to it can be found in the script, meaning that it was probably scrapped before it could be contextualized within the story.

While Suda’s script is still, due to the circumstances, likely the weakest one he had produced up until that point, a lot of the differences between No More Heroes 2 and the company’s previous outings can be attributed to staging and presentation. For example, the lecherous element which the game is known for is pretty much absent from the script.

The original No More Heroes happened to have some attractive female characters, but the only one being overtly sexual was Sylvia herself, specifically as she’d use her charms to puppeteer the men around her much like Fujiko Mine in the Lupin the IIIrd franchise; Marvelous had latched on to this element to advertise the game in Japan, going as far as to hire several gravure models to take sexy photographs cosplaying as Sylvia herself for an advertisement blog.

This element, much like the focus on sci-fi, crass humor and pop culture references, was similarly made much more prominent in Desperate Struggle. Just as the lens of pop culture addiction was turned inwards, making the entire setting an extension of Travis’ obsessions, the same is true for his sexual desires, with the game featuring several gratuitous shots of Sylvia’s thong and Shinobu in the nude, with one of the female bosses even showing off butt-cheek jiggling mechanics as she is being mercilessly cut to pieces.

The staff working on cinematics was pretty much unchanged from the original No More Heroes, so I can only surmise that the change in presentation was dictated by the overall directorial change, though I can imagine they were also nudged in that direction by the producers at Marvelous.

Hilariously, there was even a line of lingerie produced specifically to advertise the game.

Some subtler and more interesting elements still manage to emerge in the finished game: for example, the entire story is framed as a tale told by Sylvia as she is forced to work in a peep-show after inexplicably going bankrupt. This is obviously inspired by Paris, Texas, one of Suda’s favorite movies, that happens to star a main character named Travis, played by Harry Dean Stanton.

The story also very subtly implies that the assassins Alice Twilight and Margaret Moonlight (obviously a play on Twilight and Moonlight Syndrome) were sisters, a detail that can only be caught by extracting the textures of the photographs that Alice is shown burning in a cutscene.

On the gameplay side of things, as I already mentioned, the open world from the original was completely scrapped, and so were the participation fees. The game still allows the player to partake in side-jobs, but they are this time presented as 8bit minigames, once again reflecting the change of framing from “a game about an otaku gamer” to “a game for otaku gamers.” The training sessions also make a return, though unlike with the original, they do not tie into the main story, with Travis’ trainer being a goofy gay man similarly absent from the script.

The player can still spend money on purchasing new dussles, however Mask de Uh, though returning as a store owner (his store is, this time, called Airport51, after Suda and Mask’s written review column), would not provide their designs. As such, the game’s fashion leans less towards the 70s punk revival aesthetic and more towards self-referential geekdom.

In terms of combat, the extremely simple yet somewhat strategic approach of the original has been replaced with constant button mashing, with enemies and bosses being mostly vulnerable at all times, which is made up by sometimes absurdly inflated health pools and unending enemy waves.

Some variety is added by giving more options to the player in terms of weaponry, allowing Travis to switch between four different Beam Katanas during combat rather than carrying only one, and by making Shinobu and Henry playable for short segments. Unfortunately, combat is also made substantially clunkier by cutting the framerate in half compared to its predecessor (60fps vs. 30fps), cluttering the screen with effects to mask the low framerate, making everything even more chaotic and unintelligible.

The main composer for No More Heroes 2 was the newly-hired Akira Yamaoka, most known as the composer of Silent Hill, who had left Konami to join GhM in February of 2010 to work on Shadows of the Damned and Desperate Struggle. At the time, it seemed weird that such a high-profile composer would leave a huge company to join an expanding, yet small studio like Grasshopper Manufacture.

Since then, more information has surfaced about the draconic work conditions at Konami, especially in regards to the treatment of their ex-employees; while this scandal mostly revolved around Hideous Kojima (developer of Metal Gear Solid) and Koji Igarashi (producer of the Castlevania series in the latter half of its history), it is possible that Yamaoka himself had no choice but to join a company with a lower profile.

It seems that, much like his parallel work with Shadows of the Damned, Yamaoka was mostly left free to compose the soundtrack however he saw fit: he enlisted the help of several other composers, too many to list here, but one noteworthy contributor was Kazutoshi Iida, developer of Aquanut’s Holiday, Tail of the Sun and Doshin the Giant, who had joined GhM around the same time as Yamaoka and composed the track “The Riot – Teens of Anger” while providing vocals for two more tracks, “No More Riot” and “No More No”. This is notable for being his only material contribution to the company.

Unfortunately, this is where the specter of “personal opinion” rears its ugly head: while Yamaoka is indeed a very gifted composer, I feel that his work does not gel with the sound design of Jun Fukuda as well as Takada’s did; most of the soundtrack, while good in isolation, fails to stand out, drowned out by the cacophony of battle, and it is also pretty much disconnected from any events taking place in the game, with a few notable exceptions such as “Philistine”, a song detailing the backstory of assassin Margaret Moonlight through its lyrics, written by Nobuhiko Sagara, during the fight itself.

No More Heroes 2: Desperate Struggle released in the United States in January of 2010 to little fanfare. The following year (June 2011) saw the release of Shadows of the Damned, which, as I already established, was a far cry from the original passion project which started off as Kurayami. With the release of these two games back-to-back, the new direction of the company was set in stone: what audiences and advertisers alike latched on to was the focus on self-referential humor, gamer culture, over-the-top violence and sexuality. As the company continued to grow and get involved with international producers, their output had to cater to the needs of producers and consumers, rather than to the whims of a handful of artists.

It should also be noted, however, that neither game was a financial success: Desperate Struggle sold below expectations, about a third of the original, and it was actually outsold by No More Heroes: Heroes’ Paradise, a remake of the original game for PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 developed by feelplus, with no involvement from Grasshopper Manufacture. Meanwhile, Shadows of the Damned received little to no promotion and was considered a financial failure.

Desperate Struggle was then released in Europe in May, this time completely uncensored, and finally in its motherland of Japan in October.

It’s possible that the game was originally intended to be fully voiced in Japanese, as this trailer seems to imply, but the release ended up only including an English track. It was also accompanied by a couple of ancillary products: The pre-order bonus Erotica Comic featured some pin-up illustrations of the game’s female cast, art of Travis’ favorite magical girls and some 4koma, but also included a short manga, No More Losers, drawn by Yusuke Kozaki, detailing the backstory of Travis’ first opponent in Desperate Struggle, Skelter Helter. As I previously mentioned, the DVD included in the Japanese-only Hopper’s edition also included a short prequel movie, No More Heroes 1.5, which somewhat explains the events between the two games. In it, Travis also happens to kill an imitator, which could be a reference to Yasuhiro Nightow’s Trigun.

(The shape of the glasses of the fake Travis and the fake Vash are very similar. Though I admit this is probably a coincidence.)

The bonus DVD also happened to include a recap of the original No More Heroes with all of its cutscenes dubbed in Japanese; this dub was actually produced for the feelplus remake, Heroes’ Paradise, and retroactively applied to the original’s cutscenes.

While Heroes’ Paradise is mostly irrelevant to GhM’s development history, as it was pushed forward by Marvelous without any involvement from Grasshopper, it is still interesting to look at the way it was promoted; a new, super-easy mode was added to the game, in which all of the girls would wear much more revealing outfits. Two sets of pin-up illustrations were produced, one for the PlayStation 3 version and one for the Xbox360 version, which similarly showed the girls in various sexual poses, and there was even a set of sexy telephone cards.

Suda has been quite open about the fact that these sexual overtones were forced on the company by various producers in The Art of Grasshopper Manufacture. They would, however, keep affecting the company for the next few years.

For better or for worse, No More Heroes 2 at least provided a conclusion to Travis Touchdown’s adventures, with him reuniting with Sylvia at the end, saving her from a life of prostitution and implying that the two of them will come back to Santa Destroy to fix the mess they helped create. By finding each other, the two have found Paradise. A standard, even cliched ending, but one that fit the tone established through the game, where Travis learns to care for his family and those around him and ultimately become the hero that all gamers want him to be. Suda himself stated, at the time, that while he was interested in returning to the world of No More Heroes, he considered Travis’ story to be completely wrapped up.

No More Heroes 2 was ported to Nintendo Switch in October of 2020 by Engine Software, which also handled the ports of killer7 and the original No More Heroes. The port was upscaled to HD and upgraded to 60fps, though this unfortunately caused some logic issues in minigames and boss fights. They later ported the game to Personal Computers in June of 2021, but said port is littered with bugs and crashes and has yet to receive a patch.