Part 1 – No More Heroes 2: Desperate Struggle

The original No More Heroes marked the end of the Classic Era of Grasshopper Manufacture, the main focus of this website, and the beginning of what we arbitrarily refer to as the Blondes Era.

On one hand, most of the original key figures (Ishizaka, Takada, Miyamoto, Sasaki) that helped shape the company were still part of the development team, with Suda serving as both director and writer; on the other hand, No More Heroes introduced Grasshopper’s first three blondes with Sylvia Christel, Bad Girl and Jeane, some light sci-fi elements with the Beam Katanas and, most importantly, a company mascot in the form of Travis Touchdown, three elements that would soon become staples of Grasshopper Manufacture.

However, before we delve into the Blondes Era proper, there was another title GhM developed in tandem with No More Heroes as part of the Zero series, known as Fatal Frame in the United States and Project Zero in Europe.

Zero is a Japanese horror series produced by Tecmo in which the player, usually thrust into the role of a young girl, is assaulted by ghosts which must be exorcised by using the Camera Obscura, a photographic camera built by Dr. Kunihiko Asou to pacify wandering spirits.

The first title in the series was released on Playstation 2 in 2001, and was followed by two sequels on the same console, “Crimson Butterfly” in 2003 and “Call of the Tatoo” (known as “The Tormented” in the west) in 2005. The first two titles also received expanded ports on Xbox.

Zero’s creator, Makoto Shibata, became acquainted with Suda during the 2005 E3 conference through the intercession of a Famitsu editor, and the two bonded over the mutual appreciation of each other’s games. As you already know from going to church every Sunday, Suda is notoriously afraid of ghosts, an interesting character quirk for a man who worked as a funeral director. It was actually his wife, a devout horror fan, who forced him to get over his phobia and get into the series. Meanwhile, Shibata was very impressed by the depiction of ghosts in killer7, how they’d show up in the middle of the levels, unaware of their own deaths, only to make mundane complaints.

A few years later, an idea surfaced for a fourth Zero game, this time produced by Nintendo for their Wii console; Series co-creator and producer, Keisuke Kikuchi, knew that Grasshopper Manufacture had experience with the Nintendo Gamecube hardware, in itself not dissimilar from its successor. Due to this and Shibata’s acquaintance with Suda, GhM was ultimately contracted to co-develop the game.

Suda initially rejected this proposal, but was talked into it at the condition that Shibata would also serve as co-director and co-writer, 51’s way of ensuring that the game would stay true to its roots.

A third director also came into the picture, Toru Osawa, a Nintendo employee as the company was partially funding the title as a Wii exclusive. The three directors would clash at times, delaying development, but the game ultimately came together thanks to Keisuke Kikuchi restoring order as producer.

The game was originally conceptualized as a collection of short stories with no connection to the main series; It was soon decided to instead focus on a singular plotline, although the finished product is still independent from the rest of the series.

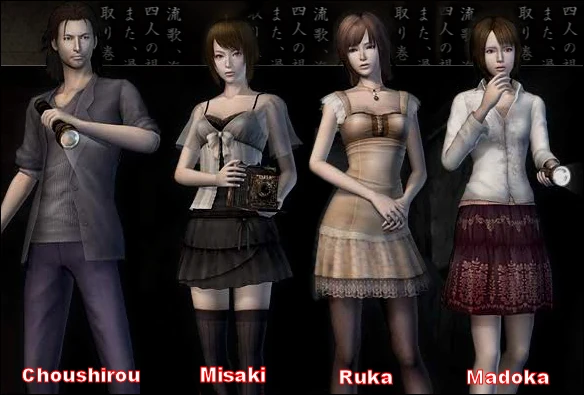

Zero: Tsukihami no Kamen begins in 1970, when five girls are abducted from a sanatorium on Rougetsu Island (south of Honshu) by alleged serial killer Yo Haibara. The girls are found unscathed in a lonely cave by detective Choshiro Kirishima, who was investigating Haibara. However, they have no memory of the events that transpired.

The five girls then leave the island; Two years later, the entire population of Rougetsu is wiped out by a mysterious catastrophe. In 1978, two of the girls, lured back by their forgotten past, die under unknown circumstances, and two more, Misaki Aso and Madoka Tsukimori, leave for the island to find out what happened to them. Madoka is quickly killed by ghosts, while Misaki’s fate is left hanging.

That’s when the two main playable characters, the previously mentioned detective Choshiro Kirishima and the fifth surviving girl Ruka Minazuki, also return to the island. Ruka fights her way through the wandering spirits using the Camera Obscura, while Choshiro has to fend them off with a moonlight-powered flashlight. Through the course of their investigation, they eventually uncover the connection between the girls’ memory loss, the death of all the island’s inhabitants, and a disease dubbed Moonlight Syndrome.

(It should be noted that, while the name of the disease, 月幽病, can indeed be translated as Moonlight Syndrome, it bears no connection with the 1997 game of the same name, which was instead spelled in English using katakana as ムーンライトシンドローム.)

Some of Suda’s hallmarks are apparent even in this short synopsis, namely the focus on lost memories and the full moon imagery. However, his contribution to the scenario was actually quite minimal:

The original arrangement saw Shibata as the main writer for the girls’ side of the game, while Suda would provide the script for Choshiro Kirishima’s sections. After receiving Suda’s script, however, Shibata was shocked by the amount of gore and violence and immediately tore it to shreds, going as far as to delete Suda’s email and purge it from his hard drive. After realizing how idiotic it was to contract an outrageous writer specifically because of his outrageous writing only to get outraged at his writing, he then tried to reconstruct his script by memory, though excising the most violent aspects. Shibata was ashamed of the profound retardation of his actions, but Suda reassured him that he did, in fact, manage to convey Choshiro’s scenario as he originally intended.

From this exchange it is clear to me that Suda was trying to channel his experience with Moonlight Syndrome, which was intended to be far more violent than how it ended up being, featuring heads exploding and on-screen decapitations. Another interesting tie-in with Moonlight is what Shibata described as the “Zero Region”. Quoting from the Suda51 Official Complete Book:

The meetings with Mr. Suda about the game were always surprising, but those things are too numerous to mention, so let me tell you about just one. One of the themes of this game for me was visualizing the scenery that lies beyond our memories. At the end of the game I wanted to show the scenery of the moment right before your consciousness is born, at the place where nostalgia for death and the consciousness of life are born, something which everyone remembers somewhere. The visions I saw and remembered of that landscape, known as the “zero region” in the game, were a chaotic, milky-white melding of light and dark, abstract and difficult to express. I knew it was probably impossible, but even if it was only as a mysterious vision at the end, I wanted to share what I saw with the players. Mr. Suda said of the place: “If a place like that existed, I’d like it to be something like ‘paradise’,” and his words influenced me strongly in realizing that final scene. It may be a very personal and trivial thing, but I wanted to talk about it somewhere.

This is, of course, starkly reminiscent of the depiction of the “edge of the world” in Moonlight Syndrome, a memory that becomes a place, which is, indeed, often associated with the concept of “Paradise” in Suda’s work.

Zero: Tsukihami no Kamen ended up being released in July of 2008, its release month being chosen specifically to tie into the Japanese tradition of sharing ghost stories and rumors around July. Much like No More Heroes, the game was entirely built around use of the Wiimote, in order to facilitate player immersion, though with markedly different aims.

While the notoriously imprecise motion controls were used sparingly in the former game, with most of it adopting a simple gameplay style and control scheme to account for them, Tsukihami no Kamen utilized them for the entirety of its core combat, which ends up feeling unfair or unbalanced because of it, even when using the Wiimotion plus periphery supposedly meant to improve precision. Moreover, the game was quite buggy, with several crashes happening at key points and certain optional objectives being impossible to achieve due to errors in programming.

Due to these and other reasons, initial plans to localize the game were scrapped. A fan translation was produced by a three-person team and released in January of 2010. The game would not see an official localization until the release of its re-mastered version in March of 2023, which featured bugs fixes, some revamped textures and a new control scheme based around modern controllers. The re-master, localized as Fatal Frame: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse in the US (while retaining its Project Zero title in Europe), was released on Nintendo Switch, Playstation 4 and 5, Xbox One and Series X, and Windows PCs.

As development on Tsukihami no Kamen wrapped up, Suda finally presented a finished draft for his personal project, Kurayami, at Grasshopper’s tenth anniversary party. Since Kurayami’s development devolved into a 3-years long bureaucratic nightmare, as detailed on its page, he would not be as involved with Grasshopper’s next release, No More Heroes 2: Desperate Struggle.

The idea to produce a No More Heroes sequel was originally verbalized by Suda himself in March of 2008, right after the European release of the original, in an interview with Computer and Videogames. The stated condition for the existence of No More Heroes 2 was that sales might satisfy the publishers, Marvelous for Japan, Ubisoft for the United States and Rising Star for Europe.

Sales were indeed satisfactory, at least for Marvelous and Rising Star. Therefore, No More Heroes 2 became the first original outing in Grasshopper’s catalog to be pushed forward due to financial expectations, rather than out of arbitrary artistic inspiration. No More Heroes was meant to be a one-off game, its subversive ending intended to stand for itself, rather than lead into a sequel.

The game was originally announced in October of 2008, during Tokyo Game Show. Marvelous and Rising Star returned as publishers for the Japanese and European market respectively, while Ubisoft was initially replaced with XSEED for North America, though they would inexplicably announce their return during the 2009 E3 conference.

As I already established, Suda was busy bickering with EA over the direction of Kurayami during development of No More Heroes 2; therefore, unlike the original, he would not direct the game. Directorial duties fell instead on Nobutaka Ichiki, who had joined the company as Planner during development of GhM’s Samurai Champloo game and had also served as co-director for the original No More Heroes and Event Designer for Tsukihami no Kamen.

Suda would provide a script for the game, but as opposed to his original outings, the script was written after characters designs by returning artist Yusuke Kozaki were already finalized, and mostly served the purpose of finding excuses for the main character to be involved in boss fights; in other words, a pretty standard videogame affair.

51 was not the only notable absentee; Original composer Masafumi Takada left the company in November of 2008, shortly after the announcement of No More Heroes 2, in order to found his own studio, Sound Prestige. Similarly, art director Akihiko Ishizaka had, by then, left GhM to join Spike, another company that was originally founded by ex-Human employees that was, at the time, about to go through a merger with Chunsoft.

The services of long-time collaborators Takashi Miyamoto, Eisin Sasaki and Masahi Ooka were likewise not requested for this title. The end result is a game that ends up feeling starkly different from GhM’s previous outputs; Up until that point, setting aside contract jobs, the company’s catalog had been a collection of wildly different and unique titles that aimed to build new game systems; No More Heroes 2 is, for all intents and purposes, a videogame like many others.

Desperate Struggle tells the story of Travis’ quest for revenge against Jasper Bat, CEO of the Pizza Bat (formerly Butt) conglomerate, who used his mafia contacts to kill Bishop, Travis’ best friend and owner of the video store, as revenge for Travis killing his family members in a few side missions in the original No More Heroes. Jasper Ass just so happens to be the number one assassin in the UAA, so Travis is once again approached by Sylvia to join the ranks and fight his way to number one to enact his revenge.

We’ve already established how well the character of Travis Touchdown captured the platonic ideal of a 2007 Burbank /b/tard thanks to Suda’s ability to channel the current zeitgeist. However, unlike characters depicted in previous Grasshopper games, it just so happened that members of that specific subculture were also avid gamers.

So it came to be that the existing fanbase for the No More Heroes games resembled Travis enough to promote him to the role of company mascot for the foreseeable future.

The specific zeitgeist the game happened to tap into, perhaps unintentionally, was the late 2000s, early 2010s trend of nerdsploitation. By then, being a “nerd” or a “geek” had become a commercialized fashion identity, in itself openly self-referential and derivative of existing pop media, be it comicbooks, sci-fi and videogames.

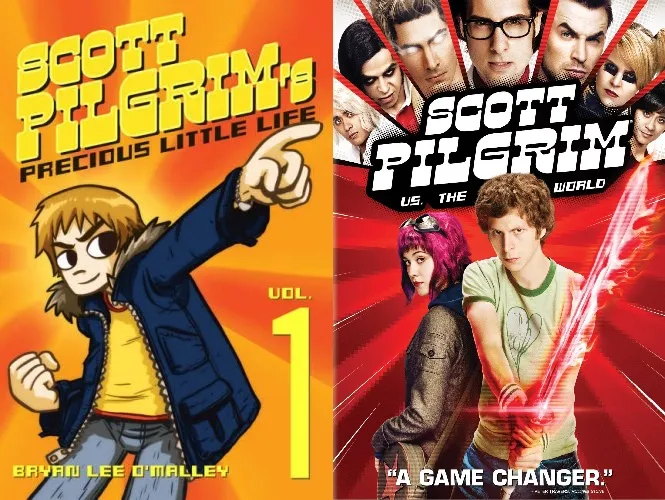

This subculture was encapsulated by the TV show The Big Bang Theory and, most relevantly to our one-sided conversation where you sit silently and I complain to you about shit from 20 years ago, the comicbook Scott Pilgrim, which was also adapted into a movie by Edgar Wright in July of 2010.

This connection is not unknown to Suda; Brian Lee O’Malley, the author of Scott Pilgrim, was a fan of No More Heroes and even went as far as to sneak Travis Touchdown in a panel of the sixth volume of the series, released shortly after Desperate Struggle, and Suda himself mentioned being a fan of the series and its author after the release of the movie.

Despite focusing in on the same subculture, however, it should be noted that the original No More Heroes did so from an outside perspective; Travis’ Chunibyo escapism was looked at through the eyes of an outsider and his character traits were depicted in the game accordingly. Chuni-like behavior was an integral part of the “geek” lifestyle. When trying to market a game to that audience, it’s clear that the lens had to be turned inwards, leading to the wild tonal shift of Desperate Struggle.

In a lot less words, while No More Heroes was a game about an antisocial otaku, Desperate Struggle became a game for antisocial otakus. As such, elements that were included in the original game due to Travis’ interest in them, ended up engulfing the entire setting, turning it wildly more farcical and exaggerated.

For example, a specific scenario sees Travis fighting a team of 25 cheerleaders piloting a mech with his own giant robot, something that he could only dream of by engulfing himself in media in the original. Through the course of the game he will fight against monsters, ghosts, and other supernatural manifestations; for all intents and purposes, the entirety of Santa Destroy has been swallowed and absorbed by Travis’ escapist delusions.

This is likely why that the fourth-wall breaking ending of No More Heroes was completely ignored in the sequel; at the end of the original game, the UAA is revealed as a non-existing organization, a scam set up by Sylvia to have lowlifes and killers part with their money as she bribed her way into high society.

Despite this revelation, Travis still elects to go through the final ranked fight: There, he is met by a man claiming to be his father, who is instantly killed by Travis’ half-sister ex-girlfriend, who reveals that she has killed Travis’ real family in the past (an episode which he has erased from his memory and can only vaguely remember in a drunken stupor) out of revenge for being raped and abused by Travis’ (and her own) father. This backstory is quite literally fast-forwarded during the scene.

Sylvia had set up the encounter specifically to allow him to get revenge, to overcome his trauma and KILL THE PAST; after that is accomplished, he is challenged by his double-secret twin brother, who also happens to be Sylvia’s husband. By this point, the reality of the game breaks down completely, with the two characters openly discussing how convoluted the plot has become, and ultimately electing to fight to the death in order to escape the game’s reality through the exit called Paradise.

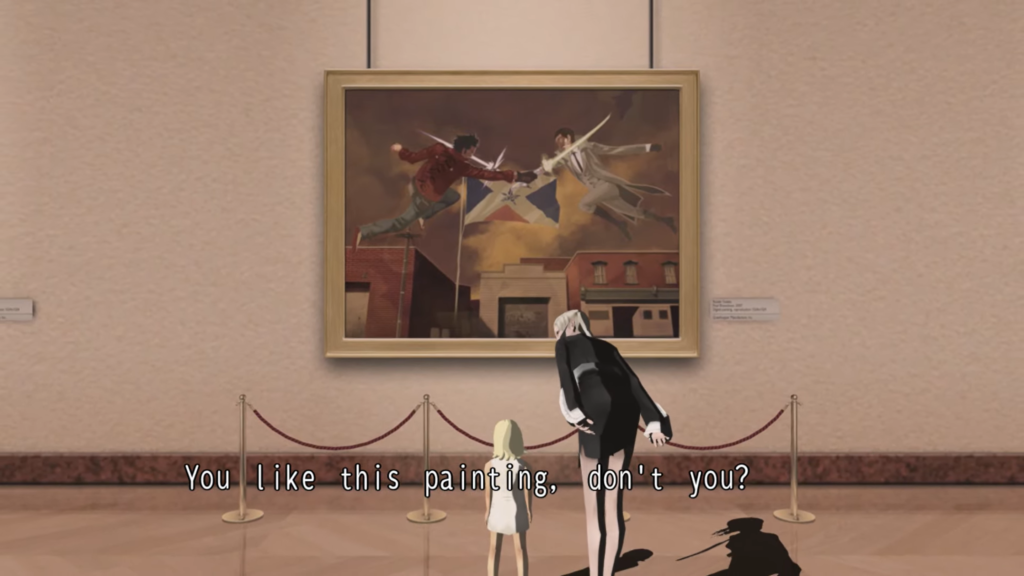

In a post-credits scene, Sylvia is shown walking her daughter (which she presumably had with Travis, as the first game implied they had sexual relations, though this point is also disputed in the sequel) through a museum, revealing that she named her Jeane, after Travis’ half-sister and ex-girlfriend who, in case you forgot, was also her sister-in-law through her being Henry’s (Travis’ twin brother) half-sister.

I don’t think it’s a stretch to assume that such an absurd series of events was intended to poke fun at the general tropes of videogame storytelling, and on a deeper level to signify Travis’ willingness to break out of his trauma-induced delusions and join the real world. This is likely why most of these revelations, outside of Henry’s role as Travis’ twin brother, are completely ignored or contradicted in the sequel, where the UAA is treated as a legitimate organization and the absurdity of its plot is never acknowledged.

The morality of Travis’ actions is also framed in a much more pandering way; as an audience surrogate, having him be the initiator of violence, occasionally killing civilians for money as he did in the original, would be unacceptable.

Therefore, a frankly bizarre balance is achieved by first having Travis casually accepting the task of killing 50 people under the promise of a blowjob, only to then provide a righteous motivation for him to engage in manslaughter.

At the same time, while the original took time to establish that Travis was not in any way morally superior to his rivals, every one of Travis’ enemies in Desperate Struggle is either a monster in need of extermination, an evil villain whose death is inherently righteous, or a devout follower which longs for nothing more than to die at Travis’ hands. This is compounded upon by the fact that the hitman assignments of the original have been completely excised, replaced instead by “revenge” missions in which Travis takes down the mafia goons that killed Bishop.

Framing the player character as a morally righteous God in order to facilitate juvenile power fantasies within the context of a game was nothing new even back then; it is, in fact, standard procedure in videogame writing. It is only a novelty in the context of Grasshopper’s previous work which was, with the exception of Contact, mainly aimed at adults.

Travis had, for all intents and purposes, metamorphosed into “One More Hero”, one that enacts righteous justice and makes every woman fall at his feet. In doing so, Desperate Struggle retroactively destroys the context of the original game, by justifying and celebrating Travis Touchdown’s escapist delusion to pander to an audience which, just as he did, decided to drown out reality under an endless barrage of juvenile fantasies.

The fact that the actions of a protagonist must only be morally righteous in the context of a Manichean good vs. evil struggle has since then been popularized in all forms of pop media in the anglosphere, likely helped by the extreme rise in popularity of superhero media during the 2010s, to the point of having drowned out the existence of unidealistic protagonists as a concept. The idea being that any sort of story can only be a morality tale, in which characters who commit foul actions must be punished accordingly by the narration in order to imbibe a lesson into the viewer.

To see an example of this one needs to look no further than how the game is perceived in the year of our lord 2023, thirteen years after its initial release: Twitter users were completely scandalized to discover a scene in which Travis is complicit in the killing of two black women, as the protagonist’s morals do not, in this case, align with those of the user, which is now understood as a mistake in the writing. (Specifically, the implication is that Travis, and by extension the game, is racist. As the killing of twenty-five cheerleaders and several civilians in the previous game’s hitman missions did not elicit any reaction, meaning that manslaughter is not the issue.)

Of course, this mostly applies to the anglophone world, as most real countries are still allowed to produce media aimed at adults that is unafraid to delve into darker and more controversial aspects of the human experience; As the game was produced in Japan, this may seem unimportant, but I will remind you that sales of the original No More Heroes were disappointing at best in its motherland, meaning the sequel would necessarily have to cater to a foreign audience. More importantly, Japan’s entertainment industry has become more and more reliant on foreign costumers as years have gone by, as ballooning budgets necessarily require a larger audience to turn a profit.

How much of this tonal shift was because of Suda’s script? We are actually in a very fortunate position in critiquing this game in the context of Suda’s career, as the production script somehow leaked during development. The differences from the finished product are mostly minor, but at the same time pretty significant:

Ironically, the scene that caused so much uproar among submentals actually saw the rival assassin, Nathan Copeland, killing the two black women in cold blood. Their death is actually more gruesome, but if they went with this scene they could have saved themselves some headaches in the coming decades.

Nathan throws the two girls.

Unable to avoid the girls, Travis’s field of vision is obstructed.

Nathan seizes the moment and jumps.

A drill comes out of a radio-cassette player as he impales Travis along with the girls.

The girls shriek and after a desperate effort, die.

The optional revenge missions were originally meant to include terrorist attacks on various institutions; one very understated aspect of the game is that the Pizza Bat conglomerate has effectively gentrified Santa Destroy by taking control of all of its infrastructure, which is only ever hinted at in the prequel short film, and Travis would take back control by bombing office buildings and even hospitals.

Killing mission

Objective is to take over all Pizza Bat controlled areas.

Along the way are missions where player takes revenge on the five men who killed Bishop.

Criminal activity such as raiding hospitals and bombing offices too.

Missions vary depending on actions taken during battles.

Total of 20 missions. One story thread will link all the missions.

While it may seem minor, this would have framed the game much differently than just a straightforward tale of righteous revenge: the ties between urbanization and the encroaching of international capital on sovereign soil, which in turn lead to the homogenization of culture, has been a recurring theme in Suda’s work ever since his second writing job, Moonlight Syndrome.

It is also interesting to note that similar conglomerates played a major part in the cultural shift from “urban” (street-level) to “nerdy” (pie in the sky). It is possible that this was an intended theme that ended up being scrapped during development, as rivalries within the game are often framed along the lines of arbitrary fashion groups (“emo”, “goth”, “grunge” and so on) based around musical trends.

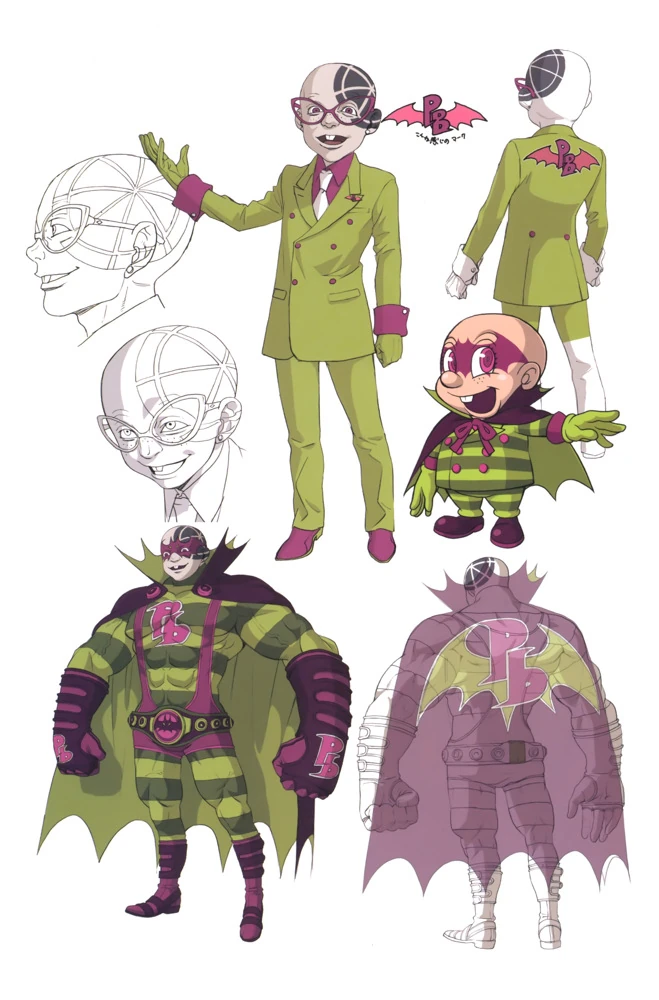

The final boss, Jasper Bat, as noted by literary critic Jonathan Holmes, is designed as a mesh between the american superhero icon Batman and his rival, the Joker. Despite Suda’s lesser involvement in the game, he has been namedropping american superheroes since at least Moonlight Syndrome, with Batman being specifically referenced in killer is dead, so it is unlikely that he was unaware of this connection. Moreover, Jasper Bat also happens to turn into a giant corporate balloon at the end, a metaphor that, while obvious, lacks some much needed context with the removal of the gentrification motif.

A third change which I personally found interesting revolves around a fan-favorite scene that utterly bewildered me: In it, Travis Touchdown, after killing the assassin Alice Twilight, goes on a seemingly random tirade about the rights of imaginary characters.

Now, I am going to be completely honest and admit that I had no fucking clue what the game was trying to say here, as in my experience living in the real world, anime characters are not, in fact, alive.

There are fringe opinions held by internet personalities such as Linkara or Chris Chan (who was, at one point, arrested for raping his demented mother) who honest-to-God believe that fictional characters exist in an alternate universe that occasionally intersects with ours, but those are absurd ideas, not something that an educated man would entertain.

Stunningly, the leaked script actually provided an answer for me: The scene immediately preceding it was altered, removing some much needed context. In the finished game, Alice Twilight praises Travis for managing to get out of the game, for walking away from a life of killing. In the original script, she instead praises Travis for being a superstar assassin, one who is able to live in the spotlight rather than hiding in shadows, setting an example which makes other people eager to fight.

ALICE:

I’ve been thinking this awhile…

As these ranking fights become an official spectator sport…

Tell me… why do all these assassins join if they’re going to end up killing each other anyway?

TRAVIS:

Does it really matter why?

ALICE:

At least to me, it’s rather important.

Living out their lives in the shadows,

if given a chance to live in the day light,

no assassin would pass it by.

TRAVIS:

You think so…

Well I got no clue what you’re talkin’ about.

ALICE:

I’m saying, everybody wants to fight you.

Don’t you get it?

TRAVIS:

Get what?

ALICE:

The one that found the daylight…

Is you, Travis Touchdown.

The idea that Travis is a superstar is somewhat hinted at in the finished game, but it is mostly brought up in the prequel movie, with the idea being that, by taking part in the ranking fights in the original game, he (inadvertently) ended up cleaning up Santa Destroy and becoming a sort of folk hero. With that context, his line about protecting the rights of imaginary characters gains a completely different meaning: what he’s actually trying to say is that these assassin fights may seem no different from any other entertainment to the spectators (movies, mangas and so on) but they’re out there bleeding and dying in the real world.

His line about tearing down the UAA, which is a plot point never brought up again in the game after that one sentence, is also slightly different in the script. The implication being that Travis will choose to lay down his weapon and stop fighting after he takes his revenge on Jasper, putting an end to the endless slaughter of the UAA (as he would stop serving as an example of a superstar assassin), with Sylvia rebutting that someone else will simply take his place, meaning the killing will never end.

TRAVIS:

The next match will be the end of the UAA.

SYLVIA:

Are you done bitching?

You could never shut down the UAA.

Ranked fights will continue regardless…

Even if you become number 1, another hero will be born.

These lines are actually unaltered in the Japanese version, meaning that the confusion must have been originated by the localization team, rather than this being an intended change from the Director; unlike the original No More Heroes, for which the translation was handled by Japanese natives at Marvelous with help from Katalyst Lab, this time Ubisoft provided a Californian localization manager, Catalina Quijano, which translated the game in conjunction with the Enzyme Testing Lab team. Katalyst Lab’s own Tad Horie, who served as supervisor for the original No More Heroes, this time directed the voice acting process instead of Kris Zimmerman.

Two other alterations exist in the script: For one, the game was meant to include an open world much like the original title. This was unfortunately scrapped during development and replaced with a menu in which the player can select the various activities. Secondly, a secret boss fight with Shinobu Jacobs was originally meant to be implemented, though no story content relating to it can be found in the script, meaning that it was probably scrapped before it could be contextualized within the story.

While Suda’s script is still, due to the circumstances, likely the weakest one he had produced up until that point, a lot of the differences between No More Heroes 2 and the company’s previous outings can be attributed to staging and presentation. For example, the lecherous element which the game is known for is pretty much absent from the script.

The original No More Heroes happened to have some attractive female characters, but the only one being overtly sexual was Sylvia herself, specifically as she’d use her charms to puppeteer the men around her much like Fujiko Mine in the Lupin the IIIrd franchise; Marvelous had latched on to this element to advertise the game in Japan, going as far as to hire several idols to take sexy photographs cosplaying as Sylvia herself for an advertisement blog.

This element, much like the focus on sci-fi, crass humor and pop culture references, was similarly made much more prominent in Desperate Struggle. Just as the lens of pop culture addiction was turned inwards, making the entire setting an extension of Travis’ obsessions, the same is true for his sexual desires, with the game featuring several gratuitous shots of Sylvia’s thong and Shinobu in the nude, with one of the female bosses even showing off butt-cheek jiggling mechanics as she is being mercilessly cut to pieces.

The staff working on cinematics was pretty much unchanged from the original No More Heroes, so I can only surmise that the change in presentation was dictated by the overall directorial change, though I can imagine they were also nudged in that direction by the producers at Marvelous.

Hilariously, there was even a line of lingerie produced specifically to advertise the game.

Some subtler and more interesting elements have managed to emerge in the finished game: For example, the entire story is framed as a tale told by Sylvia as she is forced to work in a peep-show after inexplicably going bankrupt. This is obviously inspired by Paris, Texas, one of Suda’s favorite movies, that happens to star a main character named Travis, played by Harry Dean Stanton.

The story also very subtly implies that the assassins Alice Twilight and Margaret Moonlight (obviously a play on Twilight and Moonlight Syndrome) were sisters, a detail that can only be caught by extracting the textures of the photographs that Alice is shown burning in a cutscene.

On the gameplay side of things, as I already mentioned, the open world from the original was completely scrapped, and so were the participation fees. The game still allows the player to partake in side-jobs, but they are this time presented as 8bit minigames, once again reflecting the change of framing from “a game about an otaku gamer” to “a game for otaku gamers.” The training sessions also make a return, though unlike with the original, they do not tie into the main story, with Travis’ trainer being a goofy gay man similarly absent from the script.

The player can still spend money on purchasing new dussles, however Mask de Uh, though returning as a store owner (his store is, this time, called Airport51, after Suda and Mask’s written review column), would not provide their designs. As such, the game’s fashion leans less towards the 70s punk revival aesthetic and more towards self-referential geekdom.

In terms of combat, the extremely simple yet somewhat strategic approach of the original has been replaced with constant button mashing, with enemies and bosses being mostly vulnerable at all times, which is made up by sometimes absurdly inflated health pools and unending enemy waves.

Some variety is however added by giving more options to the player in terms of weaponry, allowing Travis to switch between four different Beam Katanas during combat rather than carrying only one, and by making Shinobu and Henry playable for short segments. Unfortunately, combat is also made substantially clunkier by cutting the framerate in half compared to its predecessor (60fps vs. 30fps), cluttering the screen with effects to mask the low framerate, making everything even more chaotic and unintelligible.

The main composer for No More Heroes 2 was the newly-hired Akira Yamaoka, most known as the composer of Silent Hill, who had left Konami to join GhM in February of 2010 to work on Shadows of the Damned and Desperate Struggle. At the time, it seemed weird that such a high-profile composer would leave a huge company to join an expanding, yet small studio like Grasshopper Manufacture.

Since then, more information has surfaced about the draconic work conditions at Konami, especially in regards to the treatment of their ex-employees; while this scandal mostly revolved around Hideous Kojima (developer of Metal Gear Solid) and Koji Igarashi (producer of the Castlevania series in the latter half of its history), it is possible that Yamaoka himself had no choice but to join a company with a lower profile.

It seems that, much like his parallel work with Shadows of the Damned, Yamaoka was mostly left free to compose the soundtrack however he saw fit: he enlisted the help of several other composers, too many to list here, but one noteworthy contributor was Kazutoshi Iida, developer of Aquanut’s Holyday, Tail of the Sun and Doshin the Giant, who had joined GhM around the same time as Yamaoka and composed the track “The Riot – Teens of Anger” while providing vocals for two more tracks, “No More Riot” and “No More No”. This is notable for being his only material contribution to the company.

Unfortunately, this is where the specter of “personal opinion” rears its ugly head: while Yamaoka is indeed a very gifted composer, I feel that his work does not gel with the sound design of Jun Fukuda as well as Takada’s did; most of the soundtrack, while good in isolation, fails to stand out, drowned out by the cacophony of battle, and it is also pretty much disconnected from any events taking place in the game, with a few notable exceptions such as “Philistine”, a song detailing the backstory of assassin Margaret Moonlight through its lyrics, written by Nobuhiko Sagara, during the fight itself.

No More Heroes 2: Desperate Struggle released in the United States in January of 2010 to little fanfare. The following year (June 2011) saw the release of Shadows of the Damned, which, as I already established, was a far cry from the original passion project which started off as Kurayami. With the release of these two games back-to-back, the new direction of the company was set in stone: what audiences and advertisers alike latched on to was the focus on self-referential humor, gamer culture, over-the-top violence and sexuality. As the company continued to grow and get involved with international producers, their output had to cater to the needs of producers and consumers, rather than to the whims of a handful of artists.

It should also be noted, however, that neither game was a financial success: Desperate Struggle sold below expectations, about a third of the original, and it was actually outsold by No More Heroes: Heroes’ Paradise, a remake of the original game for Playstation 3 and Xbox 360 developed by feelplus, with no involvement from Grasshopper Manufacture. Meanwhile, Shadows of the Damned received little to no promotion and was considered a financial failure.

Desperate Struggle was then released in Europe in May, this time completely uncensored, and finally in its motherland of Japan in October.

It’s possible that the game was originally intended to be fully voiced in Japanese, as this trailer seems to imply, but the release ended up only including an English track. It was also accompanied by a couple of ancillary products: The pre-order bonus Erotica Comic featured some pin-up illustrations of the game’s female cast, art of Travis’ favorite magical girls and some 4koma, but also included a short manga, No More Losers, drawn by Yusuke Kozaki, detailing the backstory of Travis’ first opponent in Desperate Struggle, Skelter Helter. As I previously mentioned, the DVD included in the Japanese-only Hopper’s edition also included a short prequel movie, No More Heroes 1.5, which somewhat explains the events between the two games. In it, Travis also happens to kill an imitator, which could be a reference to Yasuhiro Nightow’s Trigun.

(The shape of the glasses of the fake Travis and the fake Vash are very similar. Though I admit this is probably a coincidence.)

The bonus DVD also happened to include a recap of the original No More Heroes with all of its cutscenes dubbed in Japanese; that was the first time this dub would be released, as the original game was only ever voiced in English, though it was likely produced specifically for its remake, Heroes’ Paradise.

While Heroes’ Paradise is mostly irrelevant to GhM’s development history, as it was pushed forward by Marvelous without any involvement from Grasshopper, it is still interesting to look at the way it was promoted; a new, super-easy mode was added to the game, in which all of the girls would wear much more revealing outfits. Two sets of pin-up illustrations were produced, one for the Playstation 3 version and one for the Xbox360 version, which similarly showed the girls in various sexual poses, and there was even a set of sexy telephone cards.

Suda has been quite open about the fact that these sexual overtones were forced on the company by various producers in The Art of Grasshopper Manufacture. They would, however, keep affecting the company for the next few years.

For better or for worse, No More Heroes 2 at least provided a conclusion to Travis Touchdown’s adventures, with him reuniting with Sylvia at the end, saving her from a life of prostitution and implying that the two of them will come back to Santa Destroy to fix the mess they helped create. By finding each other, the two have found Paradise. A standard, if even cliched ending, but one that fit the tone established through the game, where Travis learns to care for his family and those around him and ultimately become the hero that all gamers want him to be. Suda himself stated, at the time, that while he was interested in returning to the world of No More Heroes, he considered Travis’ story to be completely wrapped up.

No More Heroes 2 was ported to Nintendo Switch in October of 2020 by Engine Software, which also handled the ports of killer7 and the original No More Heroes. The port was upscaled to HD and upgraded to 60fps, though this unfortunately caused some minor logic issues in the minigames. They later ported the game to Windows PCs in June of 2021, but said port is littered with bugs and crashes and still hasn’t received a patch nearly two years later.

Part 2 – Minor Projects (2011-2012)

As development on Shadows of the Damned wrapped up and work began on their next high-budget production, Lollipop Chainsaw, GhM worked on a series of minor projects:

The first one was Frog Minutes, their first mobile game, initially released on iOs in March of 2011 and later ported to Android’s Google Play environment in August of 2013 by Planet G, a subsidiary of GhM which had, by that point, gone independent. The game was intended to help with the relief fund for the earthquakes that hit Japan in early 2011, with all profits being devolved to it.

Frog Minutes was a simple game, one with no storyline, where a player could collect a bunch of bugs by touching them, and then feed them to different kinds of frogs in order to catch them as his ears are gently caressed by the narration of Maaya Sakamoto. It was conceptualized and produced by Suda, while Tadayuki Nomaru, who had joined the company during development of killer7 and had, up to that point, only worked as a 2D artist, took on directorial duties.

The iOs version was fully localized, with Bianca Allen as the English narrator, while the Android version remained only available in Japanese. Unfortunately, backwards support for mobile platforms is notoriously fragile: The game soon became incompatible with current platforms, and was eventually removed from all storefronts. The iOs version was preserved, but the Android one is currently lost.

September of 2011 saw the release of Rebuild of Evangelion: 3nd Impact on Playstation Portable, Grasshopper’s first rhythm game and their third licensed title with Namco-Bandai. Several proposals were drafted, including one for an Action-RPG game, before settling on a rhythm one.

The game is specifically based on Rebuild of Evangelion, a series of cinematic reimaginings of the original Neon Genesis Evangelion TV anime show created by Hideaki Anno. As such, Akira Yamaoka remixed 30 tracks from the first two Rebuild movies, the only ones out at the time, and the game was built around his music as an unconventional rhythm game in the vein of Rez or Space Channel Five. Suda was only credited as Creative Producer.

During this time, Suda himself would pen another script, albeit in an unexpected form:

Through the course of his career, Suda had been cultivating a friendship with notorious communist and game developer Hideo Kojima, who was at that point mostly known for his work on the Metal Gear series. Kojima made an appearance on the GhM’s hosted event Hopper’s in 2005, while Suda would occasionally join Kojima’s radio show, HIDECHAN! Radio, between 2006 and 2007. In April of 2007, it was revealed that the two would team up to produce a series of products that would expand upon the universe of one of Kojima’s earliest titles, the Cyberpunk detective game “Snatcher.”

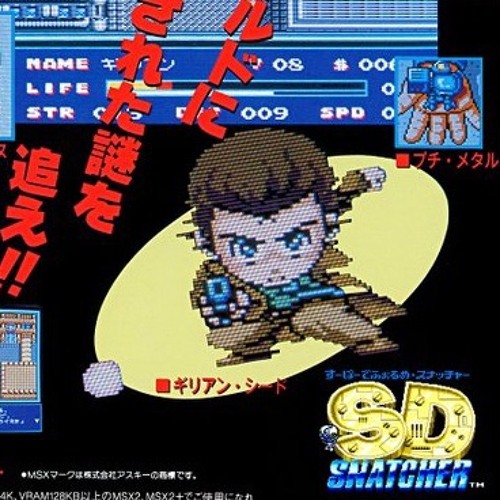

Snatcher is set in a dystopic 2047, after a bioweapon, Lucifer-Alpha, wiped out most of the world’s population. It sees Gillian Seed, a member of JUNKER, hunting down the titular Snatchers, cyborgs who snatch up people off the street only to then assume their lives thanks to a layer of artificial skin. The game’s setting of Neo Kobe, its aesthetics and its story were heavily influenced by the American sci-fi films Bladerunner and Terminator.

Snatcher was originally released in 1987 on the NEC PC-8801 and the MSX2, including only two of of the planned five chapters, ending on a cliffhanger. The story of Snatcher would be completed in the 1990 RPG SD Snatcher (With “SD” standing for “Super Deformed”, based on the game’s artstyle). Konami wanted to produce an unconventional RPG in a futuristic setting, and a decision was made to adapt the story of Snatcher into this new format. The game adapts the first two chapters and then continues on from the original cliffhanger, providing a conclusion to the story, though I am not sure if it was actually penned by Kojima: his team was busy developing Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake at the time, but they were brought in to help complete development of SD Snatcher at one point.

The original game was eventually ported to PC Engine, under the title of Snatcher: CD-ROMantic, with a brand-new third act, based on the conclusion already added in SD Snatcher, and full voice acting. That was the last version of the game to have direct involvement from Kojima; The game was then ported to the Sega/Mega CD, though this version severely toned down Hideous’ typical lecherous elements, such as Gillian being able to perv on a fourteen-years-old girl taking a shower, sniffing panties or touching breasts, and some of the violence. It also, however, featured an extended prologue (based on what was originally only shown in the manual) and epilogue. This is also the only version of Snatcher to be translated, with a fully English voiced western release. The game was then ported to Playstation and Sega Saturn with revamped graphics.

The public would hear nothing of the Suda/Kojima collaboration until August of 2011, when the “Sdatcher” website went up. Sdatcher, a portmanteau of “Suda” and “Snatcher”, would be an audio drama, penned by Suda, acting as a prequel to the original game. It follows the character of Jean-Jack Gibson, a JUNKER who meets his demise early-on in the original game, and is set in 2043, dealing with the discovery of the Snatcher menace and the foundation of JUNKER.

The radio drama was released episodically from September to December of 2011, and was eventually collected in a CD-ROM box set. Unfortunately, nothing else came out of the collaboration between Suda and Kojima. In 2016, Kojima left Konami under less than amicable terms, losing all access to the Snatcher intellectual property, meaning that Sdatcher did not only mark the end of his collaboration with Suda, but also the end of the Snatcher saga as a whole.

GhM’s next project would be another collaboration, this time with Digital Reality: the isometric shoot ’em up Sine Mora.

Digital Reality was a Hungarian studio, and their national identity actually came through in the finished game, which is an esoteric, time-warping war story starring humanoid animals. Grasshopper’s role in development was relatively minor, handling the graphics and sound design.

Newly hired concept artist Tony Holmsten created the game’s look, while Akira Yamaoka returned as composer and Jun Fukuda handled the sound design, accosted by Yusuke Komori, who joined the company during development of No More Heroes 2, and three new faces, Tristan Lewis Panniers, Ryo Koike and Yasuhito Yamada.

The game was initially released digitally in March of 2012 on the Xbox Live Arcade platform for Xbox360, and later ported on Playstation Network for Playstation 3 and Playstation Vita in July of 2013 and on iOs, Android, Windows PCs and even the OUYA in August of the same year.

Digital Reality went out of business in 2013; their back catalog was acquired by THQ Nordic, which released a remastered version of Sine Mora called Sine Mora EX on Playstation 4, Xbox One, Nintendo Switch and Windows PCs between August and October of 2017. Unlike the original, Sine Mora EX actually received physical releases on consoles.

April of 2012 then saw the release of Diabolical Pitch, a game which was originally announced as Codename D back in September of 2010. Diabolical Pitch was developed exclusively for the Xbox360’s Kinect, an accessory meant to track the player’s movement within a room, allowing them to interact with the game without the use of a controller, and also to spy on you on behalf of the NSA.

Of course, as should be expected from American manufacturers, the technology was not good enough to do either. The Kinect was notoriously imprecise. However, possibly due to their experience working with the Wii, Diabolical Pitch ended up being surprisingly functional for Kinect standards, as the movements required to progress in the game were simple and exaggerated, though obviously, when I say “functional for Kinect standards” I mean it like it is, like it sounds: the game was still wonky and imprecise at times, especially in multiplayer mode.

The game stars baseball superstar McAllister, a pitcher who dislodged his shoulder during a game, putting a stop to his promising career. After reading about the theme park “Queen Christine’s Dreamland” online, a place where all your dreams can be fulfilled, he gets into a car accident. Waking up in the aforementioned theme park, he is granted a prosthetic arm which restores its mobility. He is then tasked with completing five courses, making his way through the theme park towards Queen Christine’s Castle, as he recounts events from his past to his companion, a cow-headed talking puppet.

The courses take the form of shooting galleries, in which the player is tasked with taking down a barrage of humanoid animal puppets running towards him; this is achieved by mimicking a throwing motion after locking onto an enemy, while projectiles must be avoided by ducking or jumping. Some more complex motions are required in order to unleash special attacks.

At the end of the game, McAllister successfully defeats Queen Christine and his wish, of having his pitching arm restored, is granted, as he awakens in the real world during his final game, his injury completely healed.

Albeit a minor title, Diabolical Pitch at least shows Grasshopper’s willingness to experiment with new game systems, something they did not get a chance to do since the Nintendo Wii. It also featured some minor connections to the larger GhM catalog, with McAllister’s (who obviously shares a surname with Edo) team being the Santa Destroy Red Tigers (the apparently much more successful cousin of the Destroy Warriors), while the second player’s avatar, Eugene Guerrero (likely a reference to wrestler Eddie Guerrero) played for the Lospass Blue Legion. Guerrero’s existence is never acknowledged or explained.

While Goichi Suda received an Executive Producer credit and Nobuhiko Sagara wrote the story, two of the other creative leads, Director Hiroyuki Katano and Art Director Nozomi Kudou, are only credited in this game under Grasshopper.

Unfortunately, Diabolical Pitch was not made compatible with the Kinect 2.0 and the Xbox One console, and was, as such, delisted from stores in 2023. Luckily, the game itself has been preserved, but without the correct peripherals it will be impossible to play it in the future.

Lastly, Grasshopper Manufacture also took part in the Guild01 project, pushed forward by developer Level-5. Its stated purpose was to bring together a few small developers to create an anthology of shorter games. The three developers were Yoot Saito, creator of the 1999 masterpiece Seaman with his company Vivarium, Yasumi Matsuno, of Ogre Battle and Final Fantasy Tactics fame, who had, by then, joined Level-5, and of course, Suda’s own Grasshopper Manufacture. The fourth game of the collection was instead developed by a Japanese manzai comedian, Yoshiyuki Hirai, part of the America Zarigani duo.

Grasshopper’s contribution, Liberation Maiden, is an isometric shooter starring Shoko Ozora, the teenage-girl president of Japan most known for her huge ass, as she pilots her mech, the Liberator “Kamui”, to defeat the invading forces of Dominion who have assassinated her father and invaded Japan to steal its energy.

Suda is credited for providing the original concept, and also as Creative Director, whatever that may mean. He also wrote the lyrics for the main themes. The scenario was written by Masahiro Yuki, whose biggest contribution to the company, at this point, was writing the Matchmaker arc in The 25th Ward, while directorial duties fell on Makoto Chida.

Yusuke Kozaki, the artist from the two No More Heroes games, returned to provide his work for the heavily anime-inspired Liberation Maiden, accosted by Shigeto Koyama, Mahiro Maeda and saitom as designers for the mechs, the battleships and the enemies. The animated cutscenes for the game were produced by Studio BONES,.

The sheer number of titles produced between 2008 and 2012 should serve as an obvious indication of the growth of the company; What had started as a five-person team in 1999 had grown to about 70 by 2009, and then doubled again by the time Shadows of the Damned was out. At this point, Suda had mostly taken on a managerial role in the company, often limiting himself to drafting proposals, instead of serving as Director or Scenario Writer.

Suda was likely building up his company in order to try and bring auteur gaming into the next generation, just as Kojima, who had managed to retain a surprising amount of artistic control over his projects despite some occasional issues, once did at Konami. Unfortunately, this expansion was sometimes misdirected or chaotic: Suda’s idea, as stated by a third party, was to create a collection of individual artists who’d work on their own personal projects with shared staff, something he had already tried to accomplish in the early days of the company with Akira Ueda. However, this would not come to fruition, as the creators hired by Suda would often leave the company after a short period, sometimes without ever directing any games.

I already mentioned the short tenure of Kazutoshi Iida, but he was not the only one: Yasuhiro Wada, creator of Harvest Moon, and Yoshiro Kimura, creator of Little King’s Story, both producers for the two No More Heroes games under Marvelous, joined GhM during its expansion phase right after the release of Desperate Struggle: both of them, however, left the company in less than a year, with Suda citing differences between their work philosophy and that of the rest of the team. It would not be uncommon, through this phase, for developers to join Grasshopper only to leave quickly. Massimo Guarini, Director of Shadows of the Damned, also left the company to start his own Ovosonico shortly after the release of said game, with similar things happening to the Directors of Diabolical Pitch and Liberation Maiden.

Part 3 – Lollipop Chainsaw

Grasshopper’s next big project was first hinted at in October of 2010, when GhM’s partnership with Kadokawa Games was announced by its president, Yoshimi Yasuda.

Kadokawa was, at the time, trying to get their footing in the gaming market, and producing Suda’s comedic, “stylish action” game was going to play a part in their expansion.

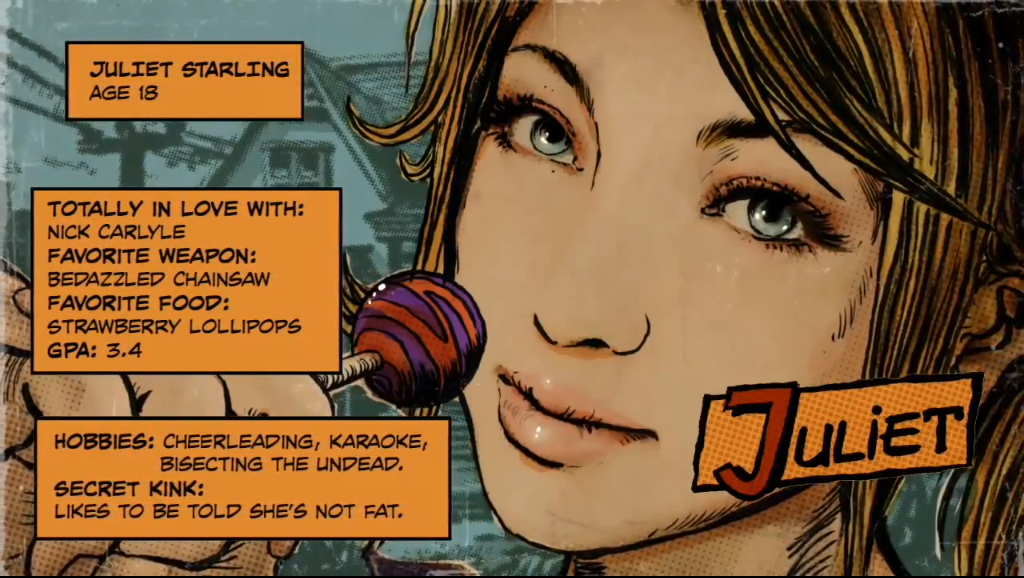

The game was ultimately revealed in July of 2011 as Lollipop Chainsaw, a comedy-horror pastiche in which 18-years-old ditsy cheerleader Juliet Starling hacks and slashes her way through a zombie apocalypse with her trusty chainsaw.

Juliet hails from a family of monster hunters, a secret she had managed to keep until, one morning, she found her high school infested with zombies. In order to save her boyfriend Nick, who had been bitten and infected, she severs his head with a magic ritual. As she carries his head around by strapping it to her belt, the two will banter during gameplay in a manner not at all dissimilar from what Grasshopper did with Garcia and Johnson in Shadows of the Damned.

Through the course of the game, it is revealed that the zombie apocalypse was initiated by Swan, a meek goth incel who, jealous of the fact that Juliet was getting plowed by her chad boyfriend on the daily, decided to open a portal to the netherworld to bring forth the Dark Purveyors, putrefying stereotypes of several music trends.

In the end, thanks to the help of her panty-sniffing teacher Morikawa and her quirky family, Juliet manages to put a stop to the zombie invasion by defeating a giant zombie Elvis Presley called Killabilly. Nick’s humanity is restored but at the cost of living the rest of his life as a manlet.

As was routine at this point, Suda drafted the proposal and was credited as Creative Director, while Tomo Ikeda, who served as Boss Designer for Shadows of the Damned, took on directorial duties. As was also par for the course, Ikeda left the company immediately after.

The scenario was penned by Masahiro Yuki, who also served as co-producer. That would be his final contribution to GhM, before leaving the company the following year to join Koei-Tecmo. He was, surprisingly, accosted for this job by American filmmaker James Gunn, who served as creative consultant.

Lollipop Chainsaw was, at the time, Grasshopper’s biggest production, with international backing from American entertainment titan Warner Bros. As such, they could work with a much higher budget than usual and enlist the help of several international celebrities, the first of which was Gunn.

Nowadays he is mostly known for directing the Guardians of the Galaxy films and threatening to produce an unending barrage of other garbage superhero movies under Warner Bros., but at the time, Gunn was still known as a fringe filmmaker who had made his bones under Troma, a production company notorious for its focus on vile and gory horror-comedies, who had only dipped his toes into the mainstream by writing two Scooby-doo live action films in the early 2000s.

His latest movie at this point was Super, a dark comedy in which a retarded man, after being left by his wife for a drug dealer, is overcome by delusions and decides to become a superhero who kills people by bashing their heads in with a wrench for minor infractions. He later enlists the help of a teenage superhero fetishist who rapes him.

His work on Lollipop Chainsaw is, by comparison, a lot tamer, but he still managed to adapt and expand the game’s brand of humor in a way that would be appealing to western audiences, helped by the more universal appeal of horror pastiche and pop music, as opposed to the more insular gamer humor of previous Blondes Era titles. He is still enamored with his work on the game to this day, referencing it as late as 2021 in his dogshit movie “The Suicide Squad”.

On the Japanese side of things, cutscenes were directed by Yudai “You Die” Yamaguchi, also known for his bizarre brand of horror, who would later gain some notoriety in the west through his participation to the anthology movie “The ABCs of Death”.

Characters were designed by illustrator NekoshowguN, and several manga artists provided additional costumes for Juliet: Rei Miyamoto and Saeko Busujima, known for “Highschool of the Dead”, Shiro, known for “Deadman Wonderland”, Manyu Chifusa, known for “Manyu Hiken-cho” and Haruna, known for “Kore wa Zombie desu ka?” all designed costumes that would reference their own works, all revolving zombie or horror lore.

The same was true for the soundtrack: While Akira Yamaoka served as Music Director, the largest part of the soundtrack was comprised of extremely popular licensed tracks, with the original compositions being handled by Digimusic Ltd. and HAL.

Most notably, electropunk singer and alleged piss fetishist pedophile Jimmy Urine, who also voiced the Dark Purveyor Zed (unrelated to Xed51), provided original songs for each of the main boss encounters and took part in promoting the game, describing it as “totally fucking crazy”.

There isn’t much to say about gameplay: Lollipop Chainsaw is a linear hack-and-slash, where the player goes through levels by hacking zombies and other supernatural creatures. Some depth is given to the combat by implementing hand-to-hand combos, which serve the purpose of stunning enemies, with the scoring system and the in-game shop being tied to executing as many enemies as possible in one swing.

Along the way, the player is tasked with rescuing civilians, with failure to do so resulting in a bad ending. While the in-game shop allows purchase of extra combos, costumes, music tracks and so on, the game contains no other side objectives or optional gameplay scenarios. It does, however, mitigate repetition by including several semi-interactive set pieces and by capping off each level with a boss fight, sometimes implementing Quick Time Events during cutscenes, a first for GhM.

After releasing in June of 2012, Lollipop Chainsaw quickly became Grasshopper’s best selling title, with over a million copies sold over eighteen months.

Its success was, of course, dictated by its broader appeal, with its focus on pop music and zombie pastiche, but it was also helped by the massive marketing campaign that Warner Bros. and Kadokawa afforded the game, something that EA did not provide for Shadows of the Damned.

Efforts were made to turn Juliet Starling into a household name: high-profile voice actors were chosen for her, with Tara Strong, which you may know as Kaede Smith and Twilight Sparkle in that fucking pony cartoon, voiced her in the US, while the Japanese version had Eri Kitamura (Saya Otonashi from Blood+, among others) playing Juliet in the Xbox360 version, and Yoko Hikasa (Saki Nagatsuka from Ro-Kyu-Bu!) played her in the Playstation 3 version.

At the same time, professional cosplayers were hired to impersonate the character. Jessica Nigri, known for being Jessica Nigri, became the face of Sexy Juliet in the west, while American-born Japanese model Mayu Kawamoto, known for being the face of Cutie Juliet in Japan, became the face of Cutie Juliet in Japan.

Obviously, as it was the standard at this point of the company’s history, the sex appeal of Juliet was extremely played up in advertising: The game featured many skimpy outfits, which were then used in promotional materials. Her entire obsession with lollipops, which colors the entire presentation of the game, is obviously meant as an allusion to oral sex. Jessica Nigri was even kicked out of PAX East for wearing an official costume that was provided to her by her employers who hired her specifically to advertise the game.

For this reason, the game was slammed by the wrecking ball of sexism: Was Juliet’s portrayal as a panty-flashing cocksucker sexist? Is the game itself sexist? Are the game developers sexist for making it? Stupider questions have been asked in the history of mankind, though rarely. We are indeed blessed, as James Gunn actually felt it was important to give a response to these accusations, carrying on the legacy of cannibal serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer as he stated, during his trial, that he was not a racist. Unsurprisingly, his comments quickly veered towards his attraction to male ass:

(…)

“Nick is objectified by Juliet — he’s literally turned into an accessory, a commodity, and his humanity is denied. Nick is not only emasculated, he is SUPER emasculated. He starts off as this cool high school jock, and he thinks his girlfriend is this demure cheerleader, and then discovers she is a thousand times tougher — that is, more traditionally ‘masculine’ — than he’ll ever be. And, on top of that, he loses his body and penis (which is just sort of the straw that broke the camel’s back).”

(…)

“But I think it’s important people don’t confuse sexuality with sexism. There is nothing in the game, ever, that makes females somehow less than males. To be honest, I think a lot of the criticisms of LC‘s ‘sexism’ are really coming from a place where the secret message is sex is bad, sexual attraction is bad, lust is bad. I was raised Catholic: I get it. Yes, Juliet Starling is hot as hell. And, yes, that probably helps to sell copies of the game. But my question is, so what? How in the world does that convey that women are less than men?”

“If you’re saying that Juliet Starling is, like Barbie, an impossible ideal that makes women feel bad about their own bodies in comparison well, okay. You have a point there,” he continued. “But welcome to NEARLY EVERY SINGLE THING IN POP CULTURE EVER. I am an avid reader of Marvel comics and, believe me, Wolverine’s ass makes me feel shitty about my own ass in comparison. Wolverine has got a tight, hot ass. If I watch the Bachelorette and those dudes take their tops off and every one of them has amazing pecs — yeah, that makes me feel like crap as well.”

Just like with Shadows of the Damned, Suda’s name was utilized quite extensively during advertisement of the game, and in the same way, he actually had little to do with the finished product: The proposal for a humorous action game starring a chainsaw-wielding cheerleader came from him, specifically citing Army of Darkness (known as Evil Dead III: Captain Supermarket in Japan)’s brand of humor as an inspiration. He did put together the team that worked on the game, especially in regards to his personal friendship with Yudai Yamaguchi, but the elements that brought Lollipop Chainsaw to success were the end result of a collaborative work of other artists, namely James Gunn, Masahiro Yuki, the already mentioned Yamaguchi, NekoshowguN, Jimmy “Old enough to bleed old enough to breed” Urine and the many musicians whose songs were licensed for the game.

Because of the sheer amount of outside influence on the project, Lollipop Chainsaw ends up feeling more of a contract job than actual licensed titles like Samurai Champloo and One Night Kiss; a competent product, but one that is not representative of the talent of GhM’s team. When mixed with the constant use of Suda51’s name during advertisement, this ended up further diluting the company’s brand identity.

Due to high sales, the game ended up being re-released in Japan the following year, on February 14th, in a special Valentine Edition box set including a series of extras. Its release was also accompanied by the single-volume release of the Lollipop Chainsaw manga, which had previously been serialized through the course of 2012 on Famitsu and Famitsu Comic Clear. The manga acted as a prequel to the game and it was drawn by debuting manga artist haru.

In May of 2022, Yoshimi Yasuda split from Kadokawa Games to found a new company, Dragami. About half of the intellectual properties previously held by Kadokawa Games were acquired by the new company, which included Lollipop Chainsaw. In January of 2023, a remake of the game was announced, and in August of 2023 its title was revealed as Lollipop Chainsaw RePOP, to be released in the summer of 2024. Suda and James Gunn are uninvolved with the project.

Part 4 – Grasshopper Universe and Planet G

In November of 2011, during development of Lollipop Chainsaw, it was announced that GhM would enter a partnership with DeNA to produce several mobile games for their Android and iOs distribution platform Mobage. The joint venture, initially called Grasshopper Social Network Service Inc., was soon renamed to just “Grasshopper Universe“. Three games were initially announced: A sequel to Frog Minutes, Alien Busters and Humans vs. Zombies. Grasshopper Universe would then also form joint ventures with Digital Hearts in March of 2012 and with Yamada Denki in September of the same year to further enhance distribution of its products.

Before we delve into them, however, I need to go on a tangent about the nature of most mobile games: The original Frog Minutes was actually an exception, a game with a definitive beginning and end (though it could technically be played forever, there is a limited number of tasks to accomplish within the game) which could be purchased fully with a one-time payment, meaning that, as emulation of earlier iOs iterations is slowly becoming possible, making the game playable on modern systems is more than a pipe dream.

The greatest majority of mobile games, however, much like the three GhM ones produced under DeNA, make their money by directing players to an in-game cash shop where they can spend real money for fake items. Meaning that, by design, they must constantly entice the player to interact with the cash shop, which has been done in several ways:

- Making game progression require a tedious amount of grind, which can be skipped by investing real-life money into powerful items, extra lives or level ups. This is sometimes tied to a stamina system, which prevents players from grinding too much within a single day.

- Adding cosmetics or gameplay-related upgrades that are only available for a limited time. This plays into a psychological phenomena known as FOMO, or Fear Of Missing Out.

These were also often paired with a “Gacha” system. Gacha takes its name from Gachapon machines, Japanese dispensers operated by inserting coins that would drop one of many figurines randomly, meaning that in order to have a full collection, one would have to spend an otherwise inordinate amount of money to beat chances and acquire the ones he needed.

Just as it is implied by its name-sake, Gacha systems in mobile games randomize the acquisition of in-game items, which are, more often than not, required for progression. While the in-game Gacha machine can be, more often than not, operated through fake, in-game currency, said currency can also be purchased with real-life money in order to avoid the tedious grind described earlier.

These systems dictate an environment in which the game must be constantly updated and changed in order to push players into the cash shop, creating a feedback loop which changes the usual structure of game development: For example, a well-known phenomena is “power creep”, a term used to describe the constant rebalancing of a mobile game, making previously required items and upgrades superfluous, in order to push the player into purchasing new ones.

It is also an inherently predatory system, and one that has also been adopted in AAA game development since the mid-2010s: It is not unusual now to see even previously single-player focused titles such as Ubisoft’s Assassin Creed or Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto include endless online modes that are tied to an in-game cash shop. Even Kojima’s own Metal Gear Solid V included such features, likely due to a push from corporate. Even the European Parlament has begun debating the morality of Gacha games and how they encourage gambling addictions among younger demographics.

Due to these reason, very few mobile games can be “completed” in a traditional sense, and the vast majority of them relied on online servers to ensure that players could not cheat their way through the game, disencouraging the use of microtransactions. Therefore, once these servers are down, the game becomes effectively lost, with no proper way of preserving its contents, most of which exist server-side.

The Frog Minutes sequel, creatively titled Frog Minutes, was released in spring of 2012. While the core gameplay remains unchanged, in the sense that the player is still tasked with collecting frogs, there is a number of differences:

For one, the player will be travelling all over the world in a variety of different locales and climates. The frogs he’ll be able to catch will depend on the time of day and weather, and sometimes by time-limited events. Instead of catching bugs to feed the frogs, players had to instead cooperate to create artificial bait. Original narrator Maaya Sakamoto was this time also accosted by a male counterpart in Tomokazu Sugita, and the player could switch between the two at will.

Lastly, the game included a Gacha system named Keropon, where the player could use the fictional currency “kero” (ribbit) to acquire cosmetics to customize his alter ego, an anthropomorphic frog, in a mode dubbed “Frog Life”. It is currently unknown if bait ingredients were also tied to the Keropon.

Both the iOs and the Android versions of the game are lost, and since the game relied on online servers to be played, they could not be booted up even if found.

This collection of screenshots was compiled by MEGAnaire. You can find him on https://deathblowicons.com/ or at the e-mail info@deathblowicons.com.

August 2012 saw the release of No More Heroes: World Ranker, in which players could create their own assassin with which to climb the ranks of the UAA, by tapping and slashing several rivals from the No More Heroes series on the screen. The game also included a PVP mode, where players could challenge each other with their own avatars. The monetization system of this game is not well documented, however, from what little gameplay footage there is, it seems that the Gacha system was tied to getting new equipment for the player’s avatar.

Likely for copyright reasons, as the No More Heroes brand is partially owned by Marvelous, this game was still published by DeNA, but not under the Grasshopper Universe umbrella.

The iOs version is currently lost, while the Android version has been preserved; however, the online servers have since been taken down, meaning launching the game only results in an error message.

A third and final game was released by DeNA in November of 2012, Dark Menace, a game in which the player, through a customizeable avatar, would shoot space aliens in space ships in space in first person, featuring some sort of cooperative gameplay. The game was likely the one originally announced as “Alien Busters” in the Grasshopper Universe press release.

The monetization system is, again, not well documented, but the game did feature a cash shop through which to trade real money for fake currency, which could then be spent on items and equipment. There was also a mode in which the player could search space debris for useful items, though it is unknown if it would have somehow tied in with the monetization.

Both the iOs and Android versions are lost, and since the game was tied to online servers that have been since taken down, it could not be booted even if found.

This collection of screenshots was compiled by MEGAnaire. You can find him on https://deathblowicons.com/ or at the e-mail info@deathblowicons.com.

In January of 2013, Grasshopper Manufactured was purchased by GungHo. I will go into more details about the acquisition later, but for this chapter, it is important to note that some change-ups happened during the acquisition. The original GhM was renamed as Planet G, with Takahiro Yoshizawa, one of the managers who had joined the company during development of Shadows of the Damned, appointed as its president and CEO.

Then, a new subsidiary, this time called Grasshopper Manufacture, was created under the Planet G umbrella, containing most of the active Grasshopper staff, and all of its shares were immediately transferred by GungHo. After that, Planet G absorbed all remaining assets from Grasshopper Universe, at this point renamed as PG Universe (Yes I KNOW), effectively splitting the old Grasshopper Manufacture and Grasshopper Universe into two separate companies, the former now owned by GungHo, and the latter, Planet G, still independent, who’d continue to produce mobile games on Mobage and other platforms.

Between 2013 and 2016 they released a long list of mobile games and apps and even a few Playstation Vita and Nintendo 3DS titles, most of them lost to time; I’d like to thank Deep Wolf for compiling some of this research while fighting AZOV in the front lines of Donbass and taking out 80% of NATO’s artillery with a screwdriver and a lot of imagination.

12/03/2013 – EASY DIVER (iOs) (Android)

A diving simulator distributed by NHN Playart on LINE, an iOs/Android distribution platform similar to Mobage. Players could collect fish and items to create compositions at their leisure. Reportage on the game by gamer.jp indicates that it occasionally held time events with exclusive rewards, sometimes even featuring famous real-life aquatic animals.

This game is notable for having been directed by Kazutoshi Iida, who hadn’t contributed to the company since providing a few tracks in No More Heroes 2. Meaning that he actually stayed behind in Planet G instead of joining GungHo with the GhM team.

Both iOs and Android versions are currently lost; since the game had online functionalities, it is likely that it could not be booted even if found.

08/08/2013 – ヤマダビ Yamadabi (iOS) (Android)

Another freemium game in which the player could train horses through a puzzle game reminiscent of Bejeweled and then race them against each other, distributed by G&D, a subsidiary of Digital Hearts, and jointly developed with Yamada Denki. The game had online components and in-app purchases, so even if copies of it were found, they could not be booted.

22/08/2013 – Frog Minutes (iOs) (Android)

A re-release of the original Frog Minutes which had, before this point, only been available on iOs. Unrelated to the Mobage version of Frog Minutes, which remained exclusive to the Mobage distribution platform. The Android version included a new narration track by Shiho Kawaraki. The (multi-language) iOs version has been preserved, but the Android version is currently lost.

31/10/2013 – Boolink (PS Vita)

A student project published as a free download by Planet G. A bizarre dual-stick side-scrolling shooter set in an abstract sci-fi environment in which the player can move the two halves of his ship separately on the screen, elongating a green line between them which is the player’s hitbox, but also controls how many bullets are shot at once. The game has been delisted from the Playstation Store but it has been preserved.

A shooting game where you use two sticks to control your own aircraft and options, and defeat enemies that appear one after another with attacks fired between the two aircraft. There are also various power-up elements. You can play alone, but it’s even more fun when you play with friends!

Playstation Store

2nd Game Campus Festa winning work

Developed by: Nihon Kogakuin College Kamata Campus/Team “LINKS”

31/10/2013 – Genimus (PS Vita)

Another free student project, dual-stick sci-fi shooter published by Planet G. This time, the player controls two separate spaceships as they are thrust in an endless corridor with each of the sticks. While delisted from the Playstation Store, it has been preserved.

An action game in which two aircraft, red and blue, push through a tube-shaped map while passing through fixed positions. Basically, another player operates the left and right sticks on the PS Vita. “Two people can play using one device” – a new way to play!

Playstation Store

2nd Game Campus Festa winning work

Developed by: Nihon Kogakuin Hachioji College / Team “grolia”

31/10/2013 – 迷球 MeiQ (PS Vita)

Another free student project. A puzzle game in which the player is task with guiding a ball through a labyrinth by using gyro controls, published by Planet G. Not to be confused with MeiQ: Labyrinth of Death, its title is a verbalization of the Kanji for “stray ball”. While delisted from the Playstation Store, it has been preserved.

An action puzzle adapted from a nostalgic maze game for PS Vita. It uses a gyro sensor, and by tilting the main body, it rolls the ball without falling into the hole and guides it to the goal. Simple but addictive!

Playstation Store

2nd Game Campus Festa winning work

Developed by: Kyoto Computer Academy/Team “Ariadne”

31/10/2013 – 桜花爛漫 Oukaranman (PS Vita)

Another free student project. A platforming game based on an eastern fairy tale. Though delisted from the Playstation Store, it has been preserved.