While Killer7 put Grasshopper Manufacture on the international map, its release also meant that the company was once again out of work. In order to resolve this third financial crisis, the company accepted a contract from Namco Bandai to produce two anime-licensed titles for PlayStation 2 consoles.

The first of the two would be based on the 2004 Shinichiro Watanabe show Samurai Champloo.

Champloo is the story of the outlaw Mugen and the ronin Jin, accompanying the young girl Fuu in her quest towards Nagasaki, to find the Samurai who smells of sunflowers. Stylistically, the show had an anachronistic slant; despite being set in the late Edo period, it depicts a stylized version of Japan where ancient and modern technologies and cultures mix together with a hip-hop soundtrack.

Due to the show’s episodic nature, the videogame (which was re-titled as “Samurai Champloo: Sidetracked” in the west, but was simply named after the anime in Japan) is framed as a lost episode set in the middle of the quest in which the three protagonists, under the false promise of free food, are lured into a boat trip to the Ezo region, where they become entangled in the conflict between the ruling Matsumae clan and the native Ainu people.

Unlike GhM’s previous licensed titles, Suda51 actually wrote and directed the game, making this his first foray into real-time action gameplay without Mikami’s oversight. Alongside programmers Kawakami and Watanabe, he crafted an original combat system where the the player mixes between two turntables to change combo strings as well as the background music.

Killer7’s legacy is quite apparent in the game’s progression, with both games sharing the same Progress Programmer, Noboru Matsuzaki. Despite having full three-dimensional movement, each level is segmented in linear hallways with progress between each of them being quite literally gated by having to collect a certain number of items (in this case Koban coins) to pay off the gatekeeper.

However, unlike Killer7’s Soul Shells, these tokens are not collected through exploration and puzzle solving, but are randomly dropped by the nigh-endless waves of enemies. This is where the game design unfortunately begins to fall apart; the enemy waves lack any interesting interactivity with the player, with Mugen’s sword-fighting in particular being ill-suited for the challenge, his acrobatics often making it harder to hit anything on screen.

This is compounded upon by the fact that the game’s two optional collectibles, pieces of concept art and additional weapons, are also unlocked by grinding the same enemy waves:

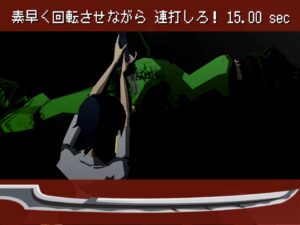

After maxing out the character’s tension gauge, represented by a dancing stickman in the bottom-left corner of the UI, an enemy will occasionally spawn with stars floating around his head. Hitting this enemy will trigger Tate mode, in which the player will challenge the enemy to a round of button mashing. If 100 hits are reached, the stage will shift to Trance mode, where the player will have to fight a hundred more enemies; this is how the game’s collectibles are acquired, which compounds upon the already mash-heavy gameplay. While these are indeed optional, the player will often be dragged into Tate mode through normal gameplay; even when trying to streamline the experience as much as possible, one would just run past all enemy encounters after acquiring the necessary kobans, resulting in an awkward gameplay loop indicative of Grasshopper’s inexperience in the field of 3D action.

The various boss fights offer more variety, with more creative setpieces and gimmicks better coalescing with the various systems, some of which would even make a return in later games like No More Heroes or Travis Strikes Again; however, they have serious issues in terms of balance, with certain fights inexplicably ending after a few hits, while others are nigh-impossible to approach legitimately, with the game triggering an in-built cheat system as a crutch after enough failures.

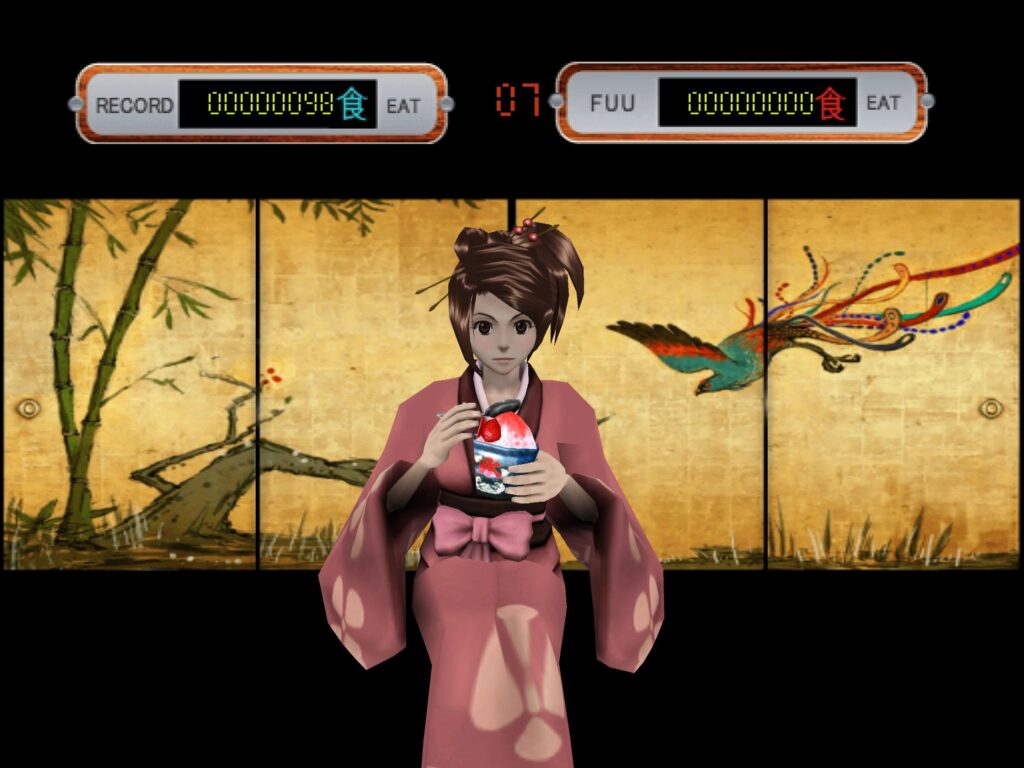

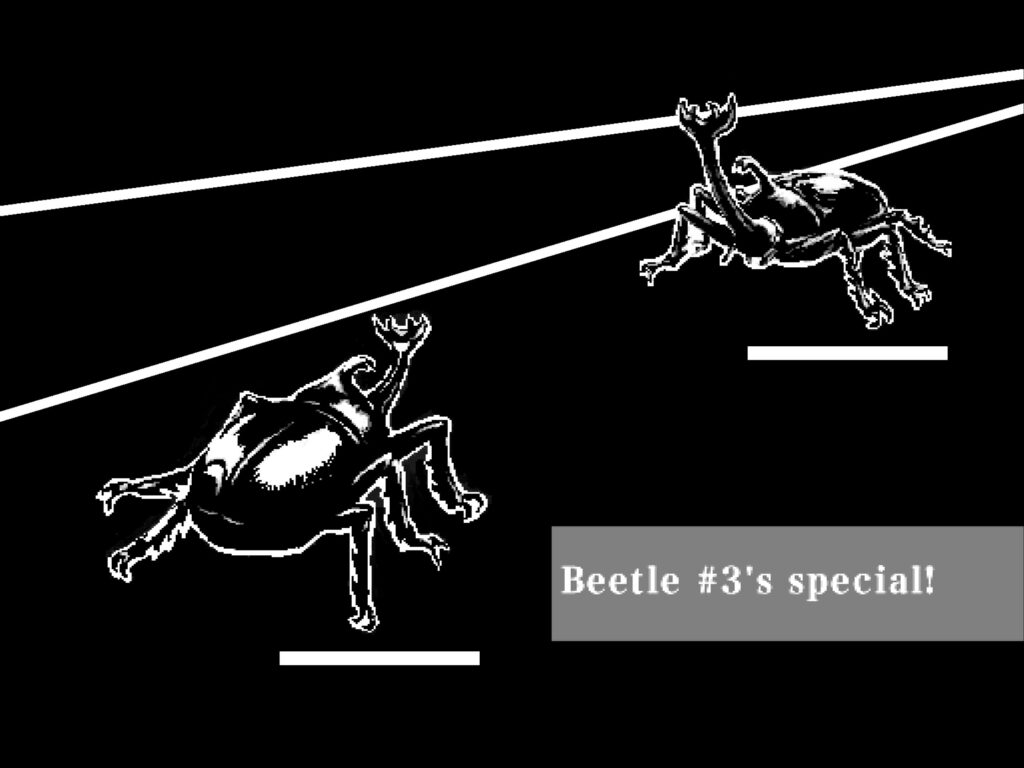

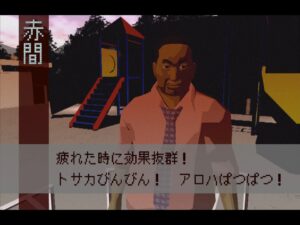

The most interesting inclusion, on the gameplay side, is that of a small, explorable town that is visited by the various characters between most chapters. The player can (allegedly) purchase new vinyls, weapons and temporary power-up items, test out their combos in the Dojo and also engage in a couple of mini-games: one plays exactly as Tate mode, with Fuu entering an all-you-can-eat challenge, while the other is a randomized game of Beetle Wrestling framed as a Pokémon parody. While barebones, it serves as one of the few examples of GhM’s eccentric game design in the title.

On the visual side, Akihiko Ishizaka’s style unfortunately did not get to shine due to the game’s dull backgrounds and locales; Ren Yamazaki’s UI design is instead quite striking, with a clear inspiration from Eisin Sasaki’s work on killer7; Sasaki, however, did not take part in active development, but he was still involved in promoting the game.

GhM was not allowed to use the original soundtrack that Nujabes composed for the show outside of the opening theme, with its music video being re-made by Jet Studio in an original, realistic style; as such, Masafumi Takada served as composer trying to align himself with the anime’s style, with Jun Fukuda handling the sound effects.

Shinichiro Watanabe himself supervised the script and voice acting, ensuring consistency with the show; the Japanese voice cast all reprised their roles, while on the western side, Mugen’s voice actor Steve Blum had to be replaced with Liam O’Brien.

Suda’s writing for the game, for which he was accosted by Masahi Ooka and Nobuhiko Sagara, ends up showing some of his more characteristic traits: his typical double narrative structure, where Mugen and Jin experience different sides of the same story, is accosted by a third campaign starring an original character, Worso, belonging to the Ainu tribe.

Near the end of his journey to re-take the land of Ezo for his tribe, Worso has to undergo a trial, fighting for his life against the remnant psyches of his strongest opponents and some color-coded technocrats, in order to dehumanize himself and face to bloodshed, awakening his bloodlust and becoming closer to the Kamui (divine spirits) in a manner quite similar as depicted in other Kill the Past titles.

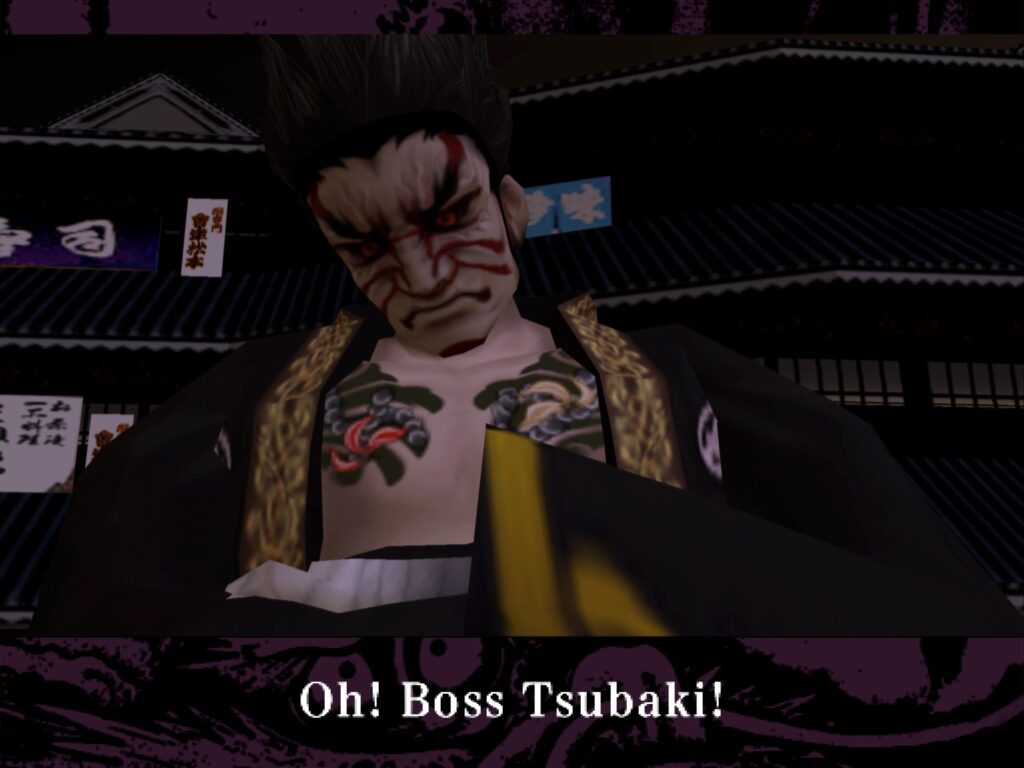

Moreover, the Matsumae’s rule is ultimately revealed as part of a conspiracy between them, a local lord, the Black Tengus of the Ainu tribe, the Oni as led by the former yakuza Tsubaki (another Suda staple) and a clan of brainwashed Yankii monkeys; in this case, the reveal is played as a joke, with the lieutenant organizing the various factions being killed off in a cutscene before his identity could be revealed, while the ultimate hidden mastermind, Lord Antonioni, is likely a parody of Japanese comedian and pro-wrestler Masaki Sumitani, a.k.a. Hard Gay.

Unfortunately, the cutscenes suffer from dull presentation and awkward pacing, and the story ends up feeling aimless, with only vague hints of the larger concepts explored in GhM’s previous work. Overall, Suda’s personal style fails to stand out outside of a handful of folk-tale intermissions, and at the same time, the game also fails in providing a satisfactory gameplay experience or to fully capture the spirit of the show it was based on. Ultimately, Samurai Champloo is, at most, an important stepping stone for the company while practicing with hack-and-slash gameplay.

Between their two anime-based titles, Grasshopper Manufacture released the Nintendo DS game Contact, an RPG primarily aimed at children in a stark change of pace from the rest of the company’s output. Other than the obvious fact that GhM’s output had been mostly aimed at mature audiences up to this point, Suda has made his dislike for RPG games quite explicit since the release of Moonlight Syndrome.

Much like Michigan, the game was initially conceptualized by Suda and later directed by Akira Ueda; the initial draft proposal, titled Cherry, saw a boy being sent by his mother to buy some cherries at the supermarket.

The boy ends up trading his money for something else, and through the course of the game he’d exchange more and more items, travelling around the world like in the story of the Straw Millionaire. In the end, the boy would acquire the cherries through one final trade and return home, where his mother would welcome him with a hug.

The initial proposal ended up being scrapped, making Contact a fully original Ueda production: the story revolves around a space-faring professor who ends up crash landing on a planet after a fight with the space communists CosmoNOTs, a separatist cell of the Barrel Liberation Front.

In order to recover the power cells necessary to re-start his ship, he enlists the help of Terry (named Cherry in Japanese), a local boy, and of the player, who interacts with the professor on the top screen and with Terry on the bottom screen. The two screens display two different art styles, stressing the fact that the professor and Terry belong in two different worlds: the top screen, the interior of the ship, shows a SNES-styled world of pixels, while the bottom screen, the outside world, has a pre-rendered style closer to Ueda’s output in Super Mario RPG and the Shining Soul games.

When the game was initially being conceptualized for Game Boy Advance, it would arbitrarily switch between the two styles depending on the situation; when development shifted to the Nintendo DS, the team decided to utilize all the system’s functionalities, and it became obvious that displaying both styles simultaneously on the console’s two screens would be the best choice.

The game is fully controlled through the touch-screen, while the in-built microphone sees some limited functionality during specific segments. Combat is triggered automatically by directing Terry to an enemy, and stat growth is determined by the actions of the player, in the sense that exposing oneself to fire will raise the fire resistance, using a specific weapon type will raise proficiency for it, and so on.

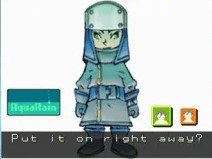

The classic job system is played with by equipping Terry with a variety of costumes that mix in classic RPG “jobs” (thief, monk) with real-life jobs that your average child might name (pilot, fire fighter). The healing system also does a good job at connecting the bizarre fantasy world of Contact to one of mundane reality; Terry will digest food in real time during gameplay, limiting the amount of healing or stat-raising foods he can ingest at once.

The player can also interact with the Professor’s pet, Mochi, an undefinable animal hybrid named Nyannyan in Japan. By taking time to play with him, the player could access a significant power-up.

This feature was apparently popular enough with the producers at Marvelous that they independently developed and released a spin-off game for Vodafone Live compatible phones named Nyannyan to Issho, where players could interact and play games with the titular monstrosity.

QUOTE OF ENLIGHTENMENT:

The cat from the Nintendo DS is now available on mobile phones!

The dream diagnosis determines what kind of pussy you will be with, so you can have your own pussy all to yourself!

Let’s pat each other on the head, go on an adventure, and make our dreams come true together.

– Marvelous Inc.

By the time of Contact’s release in March of 2006, Akira Ueda had already left Grasshopper Manufacture to found his own studio, Audio Inc., in January of the same year. In 2009, his company released Sakura Note: Ima ni Tsunagaru Mirai, a spiritual sequel to Contact, for which he was also joined by some of his old Squaresoft (by then Square-Enix) colleagues, Nobuo Uematsu and Kazushige Nojima.

GhM’s second anime-licensed title, Blood+ One Night Kiss, I tend to consider a more interesting project.

The tale of Blood actually begins with an animated movie, Blood: The Last Vampire, released in July 2000. Production I.G.’s president and co-founder, Mitsuhisa Ishikawa, wanted to produce an original animated project which was not an adaptation of previously existing material. He approached Mamoru Oshii (creator of Kerberos Panzer Cops) who, at the time, was running a series of lectures for aspiring filmmakers, and asked him to have his students submit original concepts.

Junichi Fujisaku and Kenji Kamiyama, the latter of which would also write the script, provided the initial concept of “a girl wearing a seifuku and holding a katana”, while Hiroyuki Kitakubo took on directorial duties. Kazuchika Kise, another member of Oshii’s team, served as animation director, while the character designer was surprisingly picked from the videogame industry: Katsuya Terada, mostly known for his work on the early Legend of Zelda series.

The plot revolves around Saya, an ancient vampire hunting her own kind, the chiroptera, in 1966. Through the course of the movie she’ll have to infiltrate a high-school under the guise of a teenage girl in order to exterminate the chiroptera nesting in the adjacent American Air Base of Yokota, during the build-up to the Vietnam war.

A mixed media project was produced around the movie, with three light novels, a manga and even an original interactive anime as part of the Yarudora series (which was released as two volumes on PlayStation 2, and then collected in one volume on PlayStation Portable) depicting Saya’s adventures in different time periods, including present-day Japan.

The franchise was eventually rebooted in 2005 with the anime show Blood+, co-produced by Aniplex and directed by Junichi Fujisaku, who had also written the novelization of the original film.

Blood+ does not follow the continuity of previous works. Likely taking inspiration from the manga and game, the story of Blood+ begins in present-day Okinawa. In this version of the story, Saya is an amnesiac, oblivious to her status as an ancient vampire. She discovers her role when she is attacked by a chiropteran and saved by her chevalier Hagi and eventually joins the group Red Shield, comprised of humans who have sworn to protect Saya in her fight against the chiroptera: Saya’s blood is the only thing capable of destroying them, which she is able to use through a custom-made sword that fills with her blood during fights. Through the course of the show, a conspiracy is revealed where new chiroptera are created by smuggling Delta67, a mysterious substance, through the US military.

During the initial run of the show, work began on a mixed media project similar to the one built around the original movie. A manga and a series of light novels adapted the events of the show, while two more manga and two more light novels explored different genres and events in the Blood+ timeline.

Four videogames were also produced around Blood+. One of them, simply named after the show, was a j2me cellphone game following the plot of the show, while the other three, released in quick succession between July and September of 2006 (during the original run of the show) feature original stories taking place at different points of the show’s timeline: Sōyoku no Battle Rondo and One Night Kiss were 3d hack-and-slash games released for PlayStation 2, while Final Piece, an interactive anime in the vein of the original The Last Vampire Yarudora game, was released for PlayStation Portable.

Blood+ One Night Kiss was the second anime-licensed titled that Grasshopper Manufacture was tasked with developing. As all licensed titles had to be released during the show’s original run, ONK had to be developed within a tight five-month window (for reference, killer7 took three years.)

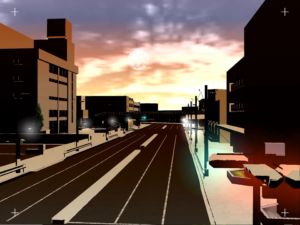

Despite that, somehow, One Night Kiss ended up being a vehicle for Suda’s ideas and aesthetics more than any kind of expansion or adaptation of the show itself. The main inspiration behind the game was to thrust Saya, who is originally from Okinawa, into an industrial setting centered around salary jobs and apartment complexes.

As such, when writing the scenario, Suda reprised certain themes he already tackled in Moonlight Syndrome with industrial society and salaryman lifestyle driving people insane, and utilizing the iconography of the apartment complex as representative of the economic system that led to their construction; even jokingly referring to the game as “Moonlight Syndrome 2” in interviews, books and in the game itself.

The stage for the game became the town of Shiki, in the Saitama prefecture. Suda just happened to visit the place due to his personal fascination with the structure of apartment complexes in new towns, and decided to send his team to scout the location in order to replicate it within One Night Kiss.

Since the setting necessitates the presence of vampires, Suda opted to use them as an allegory for the madness brought on by urbanization. Suda is credited as the only writer this time, with Sagara working on e-mails and side dialogue, but he still had to interact with showrunner Junichi Fujisaku while writing his scenario. He was apparently very protective of his creation, constantly shooting down any proposal that would deviate from the established tone of the show.

For example, Suda recalled writing two members of Red Shield, a man and a woman, helping Saya through the game who’d wear various costumes when going undercover, with ideas like having the woman dress up as a sexy nurse being thrown out especially quickly. Most notably, he also intended to feature a twist in which Saya would die at the end of the game, only for her to be revealed as a chiropteran clone of the real Saya, which angered his supervisors.

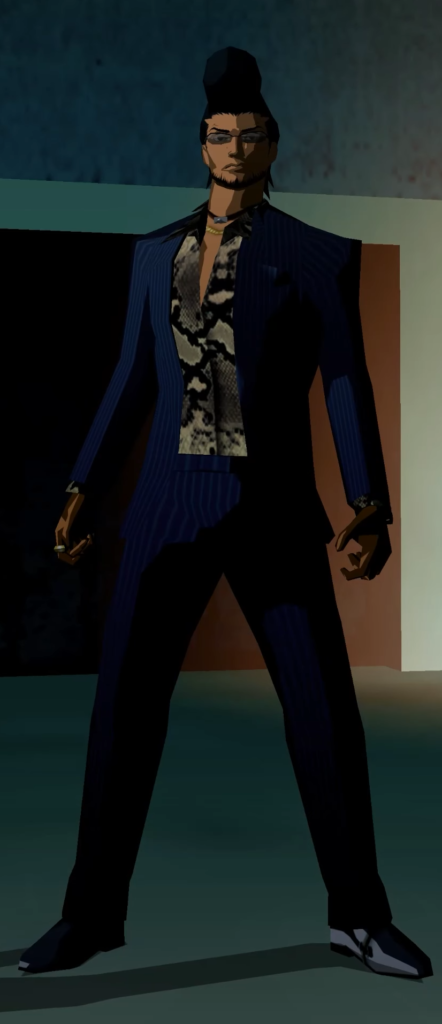

He was, however, given complete freedom in regards to the original parts of the story. Yankii detective Gou Aoyama is then introduced as a secondary protagonist, investigating the appearance of chiroptera in Shiki new town for Public Security. The core of the plot actually revolves around him, as Aoyama has a personal stake in this investigation, avenging the death of his partner Kurenai, and he’s also the one who ends up uncovering the conspiracy of Saburi Electronics, the corporation that controls the town from the shadows.

Saya is sent to Shiki to dispatch the chiroptera in a joint operation between Public Security and Red Shield, and as such she ends up feeling like a guest character in an original story. She’s tasked with infiltrating the local school as a transfer student in order to exterminate her enemies within tewnty-four hours.

The chiroptera themselves are completely unlike the ones seen in the show, with their designs resembling Heaven Smiles more than anything else. Due to their status as failed experiments, or incomplete chiroptera, they can even be harmed by conventional weaponry, with Aoyama taking down many of them with a custom shotgun, taking away Saya’s unique ability to exterminate them.

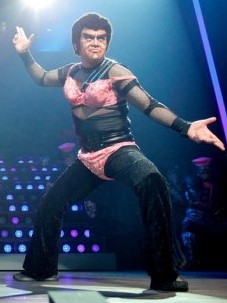

One of the inspirations when writing One Night Kiss was the stage play 轟天VS港カヲル (Gouten VS Minato Kaoru), a comedy produced by the 大人計画 (Otona Keikaku) troupe and directed by Kankuro Kudo as part of the Woman Liberation series.

As the title might imply, the play is a crossover; Ken Gouten, a character played by Jun Hashimoto from a series of plays called 直撃!ドラゴンロック (Direct Hit! Dragon Rock) by the 劇団☆新感線 (Gekidan Shinkansen) troupe, is a hero of justice and a martial arts master, but he is also a pervert obsessed with female underwear. Gouten is actually a parody of Sonny Chiba’s character in The Street Fighter.

Meanwhile, Minato Kaoru is the stage name of Sarutoki Minagawa, an actor from the aforementioned Otona Keikaku troupe. I am not entirely sure if he’s playing an established character, or if he just generally acts goofy.

Regardless, the play sees Minato Kaoru flying to the USA to shoot a movie with his manager, Park Kondo, and his 32 mistresses. However, he is too fat for the role and is rejected. At the same time, back in Japan, Minato’s third mistress is murdered by his legal wife Sonoko for making him fat, which in turn led to her diet food business going bankrupt (as nobody would buy diet food from a woman with a fat husband.)

Since Minato Kaoru is obese, his wife and her lover, Hiroshi Shirogane, decide to contract Goten to kill him. Goten has since given up martial arts and now works part-time at a Udon restaurant. Sonoko ultimately convinces him to kill the rotund Minato over lunch, which kickstarts the titular conflict.

Unfortunately, there seems to be no home video release for this play. It has been recorded, since it occasionally airs on tv, but I couldn’t find it.

What does this have to do with One Night Kiss? Well, due to this play, Jun Hashimoto (Gouten) was contracted to play Aoyama, while Sarutoki Minagawa (Minato Kaoru) was hired to play his Red Shield handler, Akama, who is, as you might have guessed, fat. (The two names, AO(blue)yama and AKA(red)ma are in themselves a pun, as the colors blue and red are often put in opposition in Japanese media, likely due to the fable of the red and blue oni. Two policemen in The 25th Ward also share the same names.)

The play contains a weird inconsistency where the character of Kazuki Nakajima, owner of the udon restaurant and likely a reference to Gekidan Shinkansen’s writer who shares the same name, is referred to as “Nakashima” by certain characters. I do not understand if this is meant to be a joke, but the same issue is present in the game, where characters will intermittently refer to a character as “Ikegawa” and “Ikezawa”. It seems too oddly specific to be a coincidence, but I am left scratching my head.

One Night Kiss is the second GhM game to be fully voiced in Japanese, and the first one where Suda had freedom in casting the original characters, as killer7 was voiced in English in all regions and Samurai Champloo mostly used the show’s cast and had Watanabe supervising the voice acting. As such, he cast actors he personally liked, like Kazuhisa Kawahara as Minoru Haraki and Tsuyoshi Muro as Akihito Yasuoka.

While all previous scenarios written by Suda contained humor, even the extremely dour Moonlight Syndrome, both Samurai Champloo and One Night Kiss take it a step further by incorporating a lot more jokes and absurd situations, which is clearly indicative of the direction that Suda would take later in his career.

However, unlike Champloo where the entire story is played out as a joke, ONK does not shy away from drama and more serious moments; instead, the humor comes organically from the character interactions, aided by casting two comedy actors in prominent roles.

Another similarity the two games share is that both of them, despite being adapted from shows that absolutely do not shy away from violence, are utterly bloodless. Obviously, that decision was made to avoid getting mature stickers on games that could realistically be purchased by teenagers.

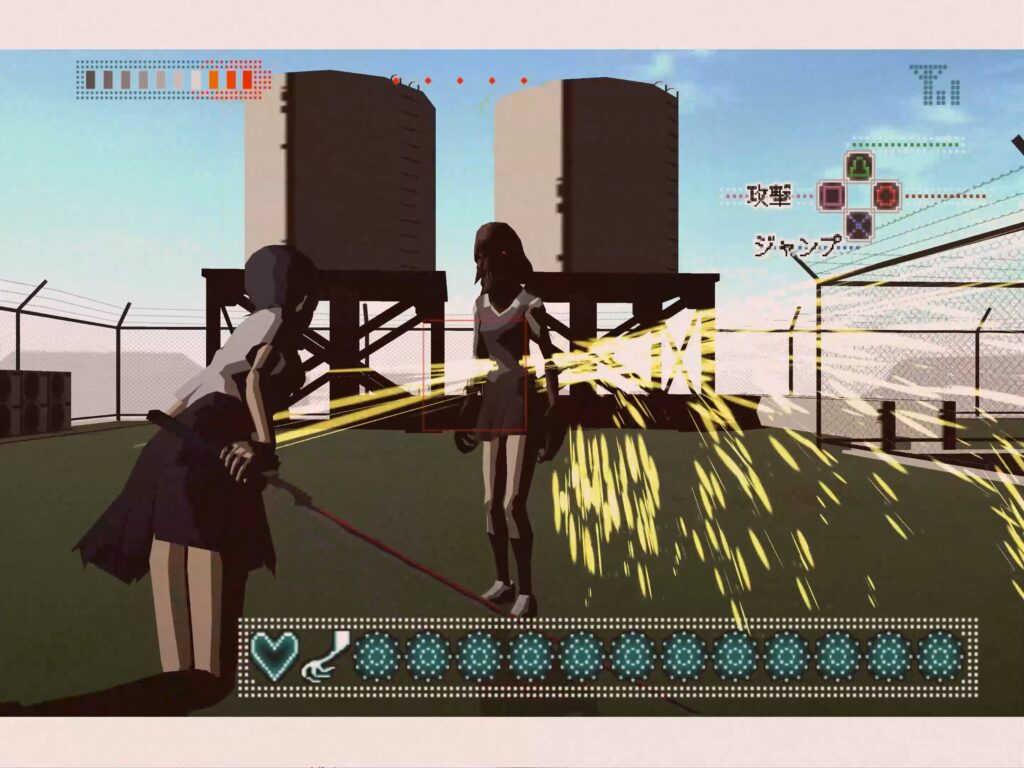

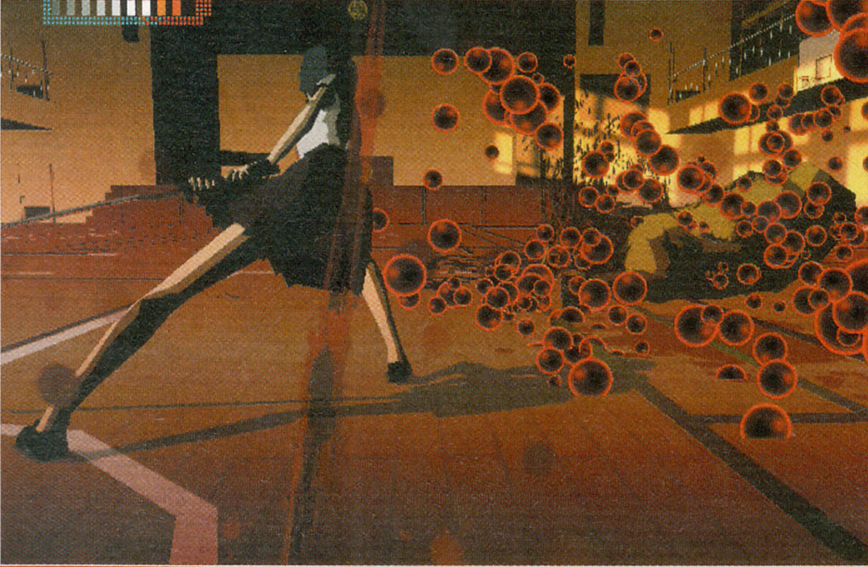

That decision must have been taken early on in regards to Champloo; an early trailer shows that originally, enemies were meant to vanish in a cloud of sakura blossoms, an idea which was probably scrapped to avoid slowdowns due to the many particles rendered on screen. In either case, however, there was no depiction of violence. One Night Kiss was instead initially meant to feature gore, as shown in these early screenshots, even including an effect where the blood would splash on the screen. In the finished game, this was clumsily censored by turning the blood sprays yellow and calling them “sparks” (they don’t look like sparks.)

On the gameplay side, the game’s progression is actually closer to Flower, Sun and Rain, in which the player, switching between Saya and Aoyama depending on the chapter, has to explore a three-dimensional world and interact with NPCs in order to locate the next point of interest.

The town of Shiki is fully realized thanks to the design of Akihiko Ishizaka and Eisin Sasaki, and the music and sound direction of Masafumi Takada and Jun Fukuda, to the point where it feels like a third main character, next to Saya and Aoyama. Much like FSR, the game is as much about uncovering the conspiracy of Saburi Electronics as it is about absorbing the ambiance of its setting when walking around.

While in FSR the player would be directed to a puzzle that Sumio would solve with his briefcase Katharine, the points of interest in ONK are boss fights with chiroptera. Saya fights them with her blood-fueled sword, while Aoyama uses a customized shotgun. While Aoyama’s gunplay functions well enough, Saya’s swordplay is almost as awkward as that of Samurai Champloo.

Aoyama’s fights are more straightforward, where shooting an enemy when vulnerable will result in immediate damage, while Saya’s hits will only serve to charge a blood meter that, once filled, will allow the player to crush one of the chiropteran’s limbs. Destroying all of them will allow you to enter a mini-game, meant to simulate the final blow on the enemy. These are different for each boss, and range from functional at best and completely counter-intuitive at worst, especially on higher difficulties.

I cannot help but think that, at some point during development, Suda planned to realize his initial killer7 plan of having NPCs transform into enemy mobs during investigations; unfortunately, likely due to the extremely short development window, the investigative aspect is largely done away with as the game progresses, replaced instead by random sewer fights with dodongos (explained in the game as animals who have mutated due to Delta67 exposure) which are also tied to an oblique leveling system, which will unlock more skills for both characters depending on the actions taken in the random battles.

It should be noted, however, that despite the extremely short development, the game is relatively bug-free: I very rarely encountered a glitch that would spawn me in the wrong location after a sewer fight, and the game has some internal logic to fix your spawn location after a few seconds. Other than that, the in-game option menu is actually non-functional, a detail which is brought up in the manual as well, and the main menu’s sound effects can occasionally glitch out.

It also features a surprising amount of extras, with a remixed campaign, unlockable costumes, side-quests and collectible e-mails with their own separate stories, written by Nobuhiko Sagara.

Overall, despite the team’s inexperience in action gameplay, One Night Kiss succeeded in embodying the values of Suda and his team, and in carrying on the will of Kill the Past as a stand-alone title. Unfortunately, that is exactly why it was largely rejected by Japanese audiences: in an ironic twist of fate, the game that posited itself as a spiritual sequel to Moonlight Syndrome also ended up being almost universally disliked by consumers for not conforming to the expectations built by its predecessor.

It’s possible that the poor reception of Japanese consumers informed the decision of not localizing the game; however, it should be noted that no other Blood or Blood+ game has been localized either.

The Blood franchise eventually continued on with a second reboot, Blood-C, a 2011 anime show co-created by CLAMP which excised the vampiric origins of the story, making Saya a sword-wielding shrine maiden defending Japan from Elder Bairns, monsters inspired by HP Lovecraft’s Great Old Ones and Japanese mythology.

As with its two previous iterations, the 12-episode animated show was accosted by several spin-offs: an animated movie serving as the story’s conclusion, three live action movies, a stage play, a novelization and two manga, one an adaptation of the show’s story and the other a side-story.