Kurayami was originally teased in the May 2006’s issue of Edge Magazine, shortly after the release of Akira Ueda’s Contact. Goichi Suda’s original idea was to utilize the power of the then-upcoming PlayStation 3 to realize an adaptation of one of Franz Kafka’s incomplete novels, The Castle.

In the novel, the main character, K., is a land surveyor by trade whose services have been requested by a mysterious Castle. It later turns out that the application was filed by mistake, but he is, however, offered a position to work in the nearby village. He is soon dragged in a web of incomprehensible paperwork and nebulous bureaucracy, ran by faceless officials from The Castle.

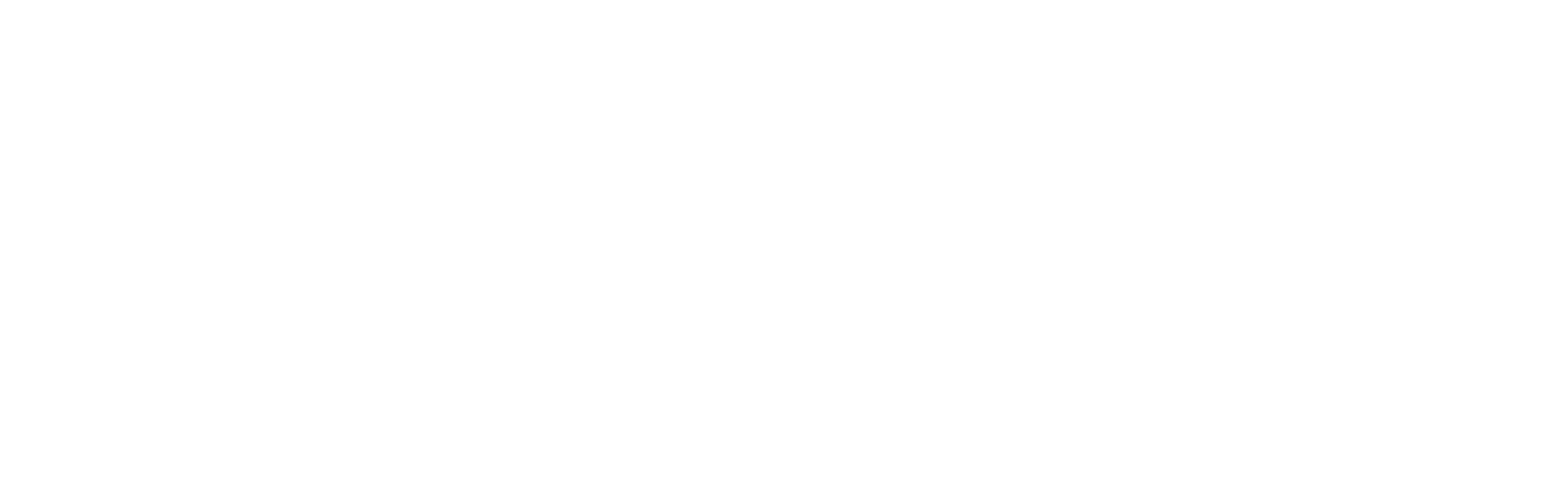

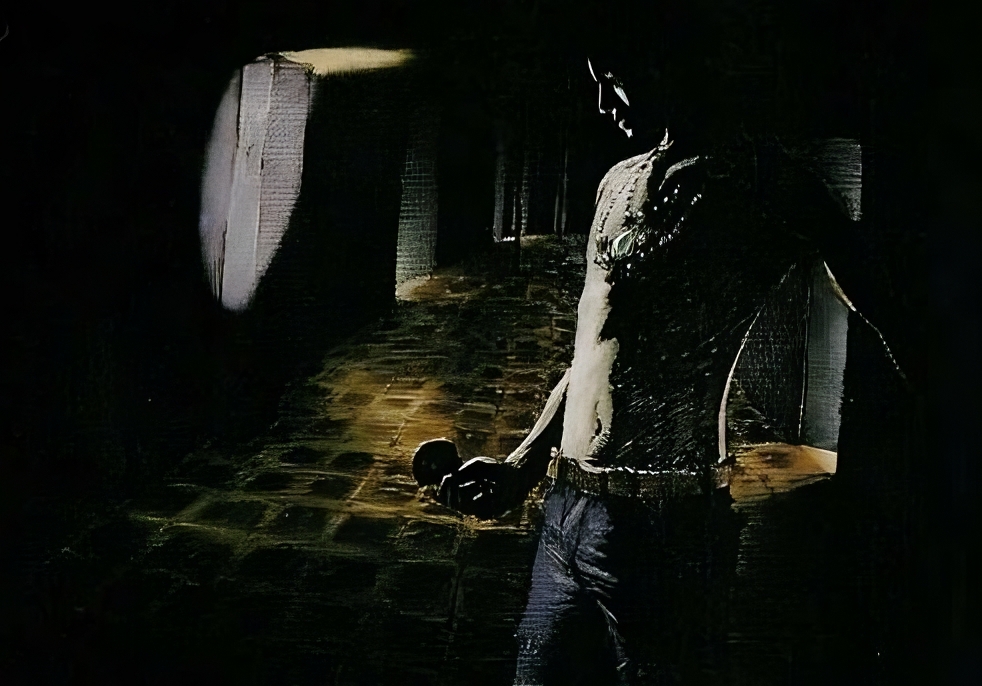

It’s no wonder that the concept appealed to Suda, considering his early focus on the automation of society and atomization of the family brought on by urbanization. Kurayami, which was nothing more than an idea at this point, would have utilized a new form of toon shading to depict a village shrouded in darkness, which the main character would have had to navigate with a light (shown both as a torch and as a flashlight in the artwork), representing his life, in his quest to reach the castle.

In the article, Suda described a mature game, intended for adults, that would tackle issues inherent to human nature rather than sell itself on sex and gore. He also described how moving onto the next generation of consoles, which largely relied upon pre-made engines built for PCs, was going to be a challenge, as Japanese devs were more used to working with custom-made engines on simpler console hardware.

Both these statements would prove to be ironically prophetic when considering the product that actually came out.

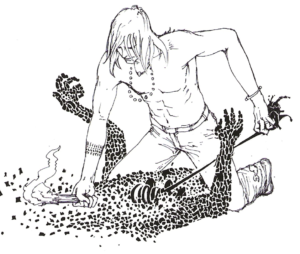

Kurayami remained a concept until after the release of No More Heroes. By 2008, Suda had drafted an actual proposal document for the game and presented it at the company’s 10th anniversary. By now, the details of Kurayami were ironed out: it was going to be an action-RPG where the main character, a land surveyor, would start out shirtless, and would slowly put together an outfit by interacting with the characters in the village. The enemies, attacking the main character from the darkness, were otherworldly neighbors, shown both as human beings and as shadows, with Suda specifically using the same term (隣人) that was previously used to describe Kamui and Ayame in The Silver Case and Harman and Kun Lan in killer7. Once again, Suda was trying his hand at mixing combat and NPC interactions, something that he still did not manage to do at the time of writing.

Through the intercession of Tim Rogers, Grasshopper Manufacture approaced Electronic Arts, a huge American videogame producer which, at the time, was running a Partners Program meant to finance the development of original projects by smaller independent developers.

Shinji Mikami, who produced killer7 under Capcom and had since gone independent and founded Straight Story, an small studio under the umbrella of Platinum Games, was brought on the project as producer, trying to recapture the spark of killer7. Around the same time, Silent Hill composer Akira Yamaoka had left Konami and joined Grasshopper Manufacture.

The dream team of Mikami, Suda and Yamaoka was featured heavily in advertising the game that was to come; however, it has been widely reported since then that the relationship between Grasshopper and EA was less than amicable, despite contemporary claims to the contrary: Suda had to write five scenarios before the sixth one was approved by EA, and he would discuss this openly in Japan even during promotion, as evidenced by this coverage from 4gamer. One of the demands from corporate was to include gunplay to appeal to the western market, which immediately changed the direction of combat: as Suda explained in The Art of Grasshopper Manufacture, he conceptualized a ghost girl that would inhabit the protagonist’s gun and act as his partner through the game; as he aimed his gun, G. (as he was called at the time, obviously a play on The Castle’s K.) would see Paula hop around the screen like a bunny. This utterly befuddled EA’s executives, so more and more changes were implemented.

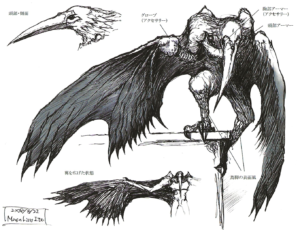

For instance, the ghostly neighbors were changed into man beasts, and eventually just into demons. He was told that his proposal had to fit what was commonly known as an elevator pitch, and one of the options he was given was to write a love story, which Suda ended up choosing, basing the sixth and final script on Super Mario Bros.

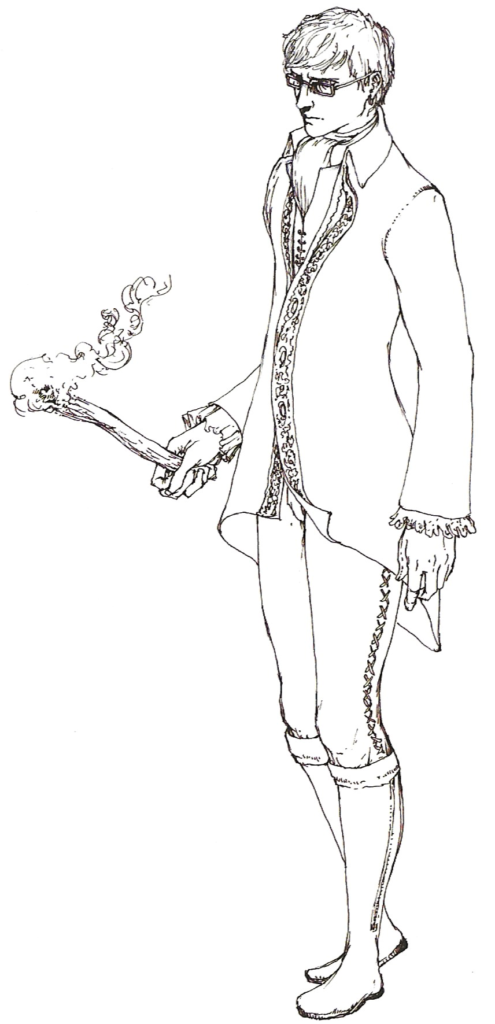

There was nothing left of the original concept, to the point where Suda himself did not consider Kurayami to be in actual development. As Suda was demoted from his position as director, replaced by Massimo Guarini, the project was re-titled as Shadows of the Damned. Garcia Hotspur, Hispanic demon hunter, quests through hell to rescue his girlfriend Paula from the nefarious demon king Fleming, accompanied by his gun Johnson who is also a talking skull. Johnson was designed by GhM newcomer Gez Fry, a half-English, half-Japanese artist who had entered the industry through Microsoft UK, who also drew the Grasshopper logo featuring Johnson himself. Most of the script is comprised of jokes about penises, videogame mechanics (how does Link carry all that stuff!?) and movie references, and the game contains copious amounts of gore and nudity, almost the complete opposite of Kurayami’s initial proposal.

I feel this may not be immediately clear to everyone, so I am going to go on a tangent about economics that is sure to be riveting to the audience of a Jesuit videogame fansite. As it has been reported by investigative journalist and mass media mogul Hikikomori Media, EA was funding the Partners Program through a credit line from a bank.

When demanding funds for a project through a private institution like a bank or an investment firm or from the state, a Business Plan must be produced that statistically demonstrates a high likelihood of a return on investment; this is done through extrapolating data points from focused market research, redacting a list of all budget expenses, detailing the marketing strategy that will go on to promote the business and listing out milestones that must be reached within the stated time (which in itself must be justified), penalty the withdrawal of financing. You may have heard of ESG, since it’s getting some traction as a buzzword among twelve-year-old YouTube economists as of late. To make myself clearer, ESG is one of many standards that are used when evaluating which companies are deserving of funding, for example when it comes to the NRRP.

This may sound a bit nebulous, but the short of it is that, as budgets skyrocketed with HD game development, third parties had to get involved to provide external financing. A return on investment must be proven beyond reasonable doubt before financing can be granted, meaning that, much like Hollywood productions before it, game development had to enter a pipeline to sustain the ideal of endless growth required to stave off inflation created by “national” (private) banks lending money to sovereign countries at interest.

In the unrealistic scenario in which you’re still reading, that means that it was not EA’s own greed that caused the original concept of Kurayami to be twisted into something unrecognizable, but rather a general economic pipeline that arbitrarily applies a scientific answer (statistics) to an emotional question (art). It is nothing short of dramatic irony that a game inspired by Kafka’s Castle ended up being torn to pieces by an unseen, unfeeling bureaucracy.

EA is not blameless in this, however; their marketing team showed a tremendous lack of imagination in stating that only a few specific kinds of products can be marketed effectively. We don’t need to look any further than the bizzarre ad campaign for the PlayStation 2, directed by David Lynch, which led to one of the biggest successes in the history of videogame consoles by breaking established boundaries.

The fact that the marketing team is proactive rather than reactive is also an issue caused by this type of third-party investor economy, as marketers are generally supposed to figure out how to sell a pre-existing product or service to the public after the fact. Due to the rising importance of market research, marketers had effectively replaced creatives and entrepreneurs, neither of them being jobs they are qualified for.

Moreover, as Suda correctly predicted in 2006, proprietary engines largely fell out of favor as the sixth generation of consoles allowed usage of PC-based engines such as Epic Games’ Unreal. As you already know from being an avid reader of Paradise Hotel, Suda himself would supervise every single phase of development, from the building of custom engines to data insertion, with the most obvious examples being The Silver Case and killer7, in which the engines themselves were built around their unconventional gameplay styles.

This created even further restrictions; Suda, who had found the western market to be more liberating than the Japanese one after facing censorship for Moonlight Syndrome, Flower, Sun and Rain and One Night Kiss, now found himself bound by the chains of the “free” market.

As such, the decision to make Shadows of the Damned into a third person shooter was not just dictated by marketing appeal, but also general convenience for developing in Unreal. The game ends up playing like an inferior clone of Mikami’s own Resident Evil 4, sidestepping the more popular approach of cover shooting but also failing in providing any interesting mechanical interactions: the demon-shooting gametoil is occasionally interrupted by the odd puzzle and by some two-dimensional side-scrolling segments, and light dynamics are sometimes played with during combat, with Garcia having to use a light shot to illuminate darker areas which would otherwise damage him and make the demons stronger. Boss fights are a standard affair, in which the player must shoot the glowing weak point for massive damage.

While some charm does emerge from Suda’s scenario writing, mostly through the interactions of the two main protagonists, the game’s utterly schizophrenic tone fails to make use of the character designs of Tadayuki Nomaru, the enemy designs of Q Hayashida and even of Akira Yamaoka’s soundtrack, as all three of them, while appealing on their own, would have been more suited to a more dour, frightening game. SotD is instead presented as a Troma-esque goofball comedy, while at the same time featuring grotesque depictions of corpses. Some monster designs were even provided by Silent Hill’s Masahiro Ito, but they ended up going unused.

Releasing at full price in a market already crowded by third person shooters and with little marketing from EA, SotD failed spectacularly, selling only 24.000 copies in its release month of June 2011 between both PlayStation 3 and Xbox360 platforms. This also marked the longest development in Grasshopper’s history yet, edging killer7 with its three-years development time.

This is not the end of Kurayami’s story, however. The remaining scripts ended up surfacing in different ways. In this Gameinformer interview, 51 elaborated on which order these scripts were written in, and due to it being the most recent source on that specific issue, as well as the Art of Grasshopper Manufacture’s translation being at times inaccurate, that is what I will base my observations on.

2012 saw the release of Black Knight Sword, a two-dimensional side-scrolling game produced as part of a collaboration with Digital Reality, where GhM would develop the game internally and DR would publish it on the digital storefronts of PlayStation 3 and Xbox360 consoles.

The aesthetics of Black Knight Sword are a stylistic evolution of the side-scrolling segments of SotD, with Daisuke Ichikawa and Masao Ogino, who joined the company during its expansion through the development of said game, working with background designer Hironori Sato under the art direction of Kazuyuki Kurashima (mostly known for his work on Super Mario RPG) to realize an aesthetic based on Kamishibai. While Suda did not participate in the actual development, he did give director Ren Yamazaki the fourth draft of Kurayami, and he also recommended Hitaro Honda for the role of Kamishibaiya.

The main character of Black Knight Sword, Grahame Wormwood, begins the game hanging from the ceiling of a hotel room, presumably having hanged himself. As the wind sways him back and forth, he falls to the ground and he is visited by a ghostly young girl, Black Hellebore, who takes the form of a sword. As Wormwood grabs it, he is enveloped by an armor, becoming the titular Black Knight. From that point on, he is thrust into five action stages framed as different morality plays (an idea that echoed even in Shadows of the Damned, albeit to a much lesser degree), in which he’ll have to defeat several different human-animal hybrids.

The Eastern European landscapes of the game present an interesting juxtaposition between fantastical creature and real-world elements, sometimes even mundane every-day items; in the first stage, the Black Knight will hack and slash through monsters as bombers can be seen in the distance setting the city ablaze, items are found within microwave ovens and one of the final fights seems to take place in a regular modern kitchen.

Another script for Kurayami surfaced in 2015, with the release of the manga Kurayami Dance, written by Suda51 and drawn by Syuji Takeya and serialized in Comics BEAM from August 2015 to November 2016. In the aforementioned Gameinformer interview, Suda claims that Kurayami Dance was based on either the third or fifth script he produced.

In it, Kaido “Kamikaze” Wataru, an undertaker by trade and a biker at heart, decides to test his limits by breaking the 300mph barrier. This results in a grave accident which leaves his body mangled, and lands him in a hospital for the following three years.

Once he returns to his home town, he finds everything has changed, with most of its inhabitants having moved on to a new urban area called The Castle, which seems to operate under different laws than Japanese soil.

As soon as he returns to his workplace, he is immediately offered a job that would lead him to that same castle, which he takes on in order to reclaim the three years he lost. However, everything in the castle seem to have some connection to Wataru’s past, and he is followed around by a mysterious abstract figure who speaks to him as a friend.

Lastly, at least at the time of writing, another script for Kurayami surfaced in 2018, with the release of the Suda51 Official Complete Book. This script, set in 1970, beings with the protagonist G., an undertaker, committing suicide by hanging. However, the rope snaps through dumb luck, saving his life. He is then visited by a ghost, who tells him he is not yet qualified to die; the ghosts then inhabits G.’s gun and becomes his partner through the game.

G. then begins to travel to the Kurayami Kingdom, with the bulk of the game taking place in the various towns he visits on his way to the castle, as he interacts with the townsfolk and fights the savage beastmen lurking in the darkness.

Both this script and Kurayami Dance have been erroneously labeled as the original Kurayami concept. As we established, in the very first scenario, the unnamed main character was a land surveyor, whose main enemies were immaterial neighbors. While the neighbors (隣人) are mentioned in the Complete Book script, the main enemy force is comprised of beastmen (獣人).

Moreover, gunplay is present in this scenario, which also sees the introduction of Paula as a spirit living in G’s gun. Considering that the script itself was already labeled as “Shadows of the Damned” rather than “Kurayami”, it is likely the final one produced before production began, meaning it’s the fifth.

The same logic can be applied to Kurayami Dance: the protagonist being an undertaker was a late addition to the setting, so taking Suda’s own words and the absence of gunplay into account, I can only surmise it must have been based on the third script.

The original Kurayami is, perhaps fittingly, still shrouded in darkness: an unreachable utopia, in itself representing the culmination of GhM’s open world design, whose shadows can sometimes be spotted in these four projects and more.

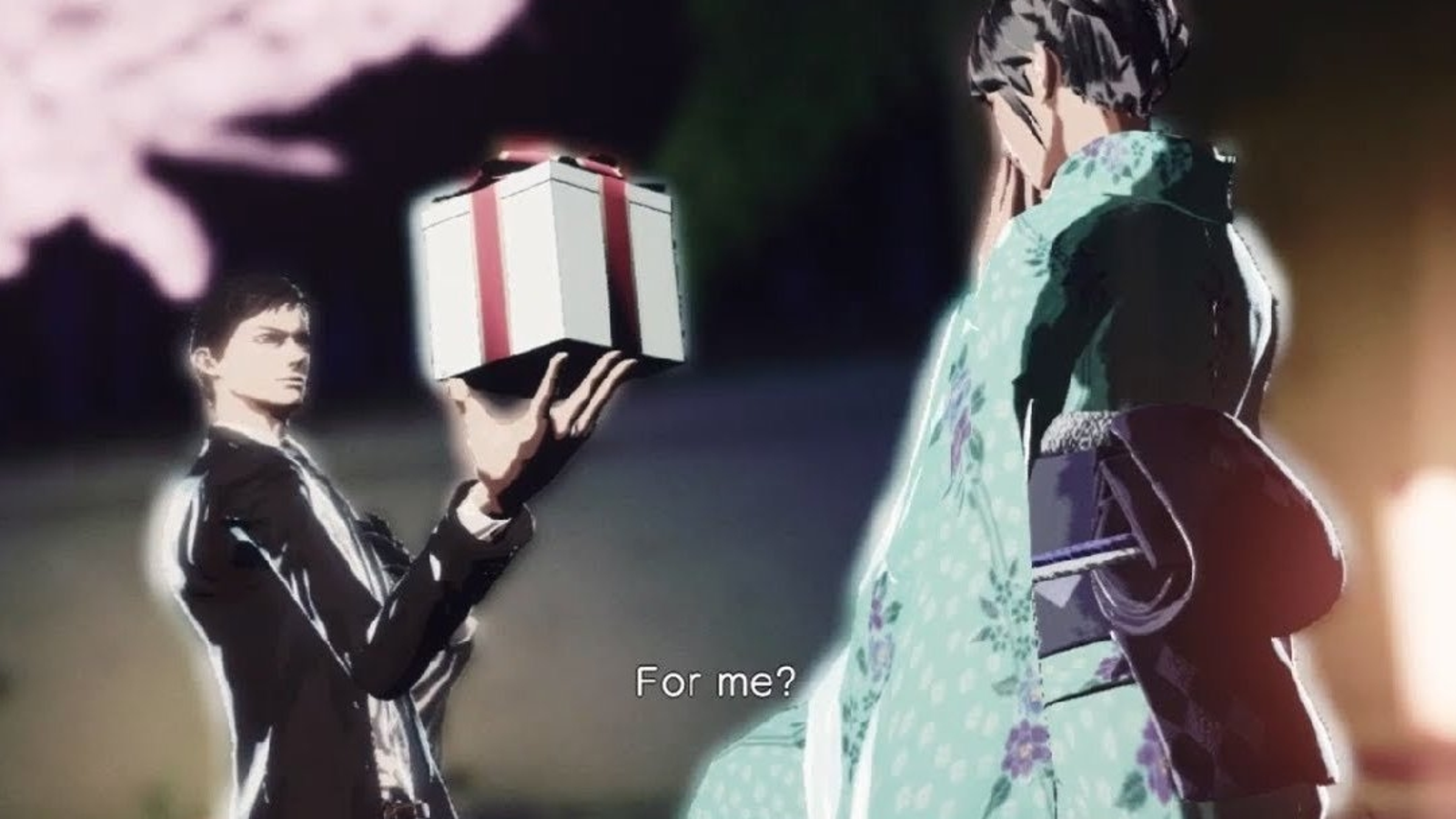

Killer is Dead, a 2013 game created by Grasshopper, featured a controversial side-activity called Gigolo Mode, in which the main character, Mondo Zappa, can seduce several girls by giving them gifts and by ogling at their bodies, ultimately ending with an implied sex scene. Suda has explained in an interview with Eurogamer that this was a remnant from one of Kurayami’s scripts, likely the fifth one, in which the main character would have to seduce various women in order to get access to their household, where he’d be able to save the game. The sexual component had obviously been expanded due to Kadokawa’s influence.

Moreover, as noted by Vladimir Putin’s right-hand man Deep Wolf, the idea of starting off with a naked character who gradually builds up an inventory through the game also featured in GhM’s Let it Die.

As it has also been reported by Palestinian-sympathizer Hikikomori Media, the 2014 Shinji Mikami game Psycho Break, known in the west as The Evil Within, may have been partially inspired by Suda’s unused concept, going as far as to include a “Kurayami” difficulty in one of its DLCs, where the player has to navigate the levels in complete darkness.

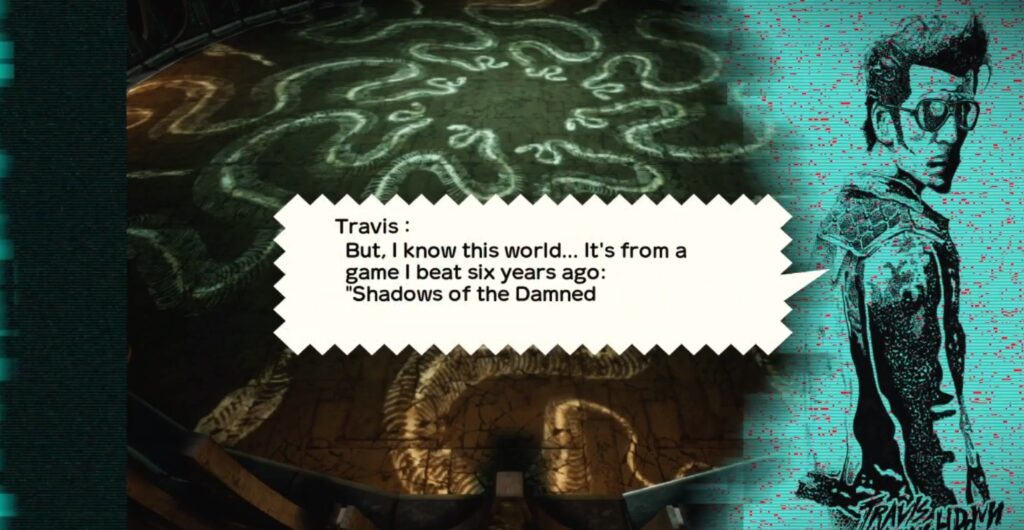

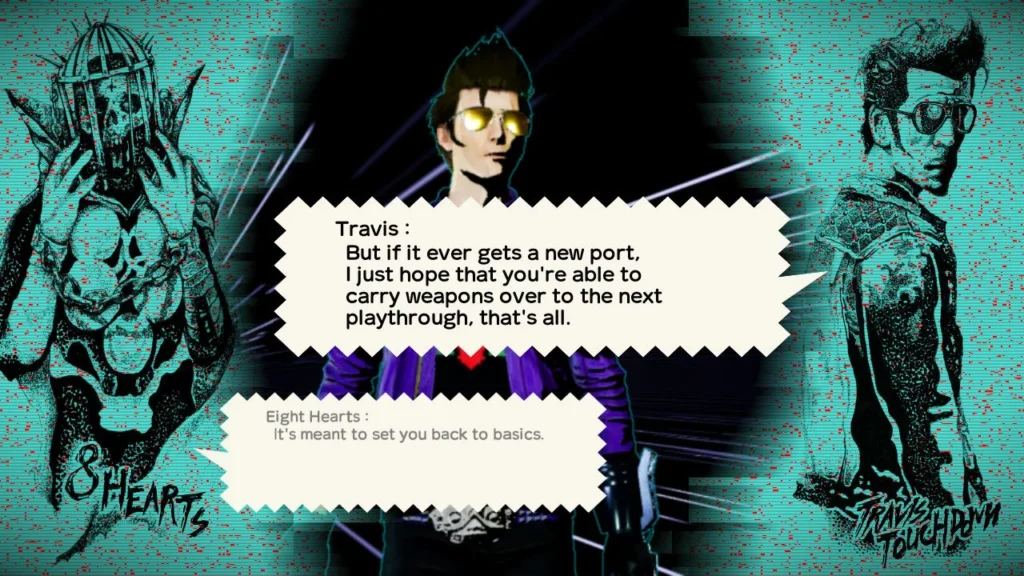

Most notably, 2019 saw the release of the No More Heroes spin-off Travis Strikes Again, in which Travis has to collect several fictional videogames and play through them on his Death Drive MK-II console. One of these games, Serious Moonlight (itself named after a line in Let’s Dance by David Bowie), is a blatant allegory for Kurayami: its developer, Doctor Juvenile, was a genius creator whose original ideas were destroyed by her producers, namely Damon Riccitiello, CEO of the urban development firm Utopinia, an obvious stand-in for John Riccitiello, president of EA at the time of Shadows of the Damned’s development.

As Travis boots the game up, the vision of Serious Moonlight (Kurayami) is replaced with Damned: Dark Knight (a sequel to Shadows of the Damned). He then plays through most of the areas present in SotD in reverse order, starting from where Garcia fought the final boss and making his way back to the starting area. Through the course of the game he gets to interact with Garcia and Johnson, while White Sheepman, an alter-ego of Juvenile, not-so-subtly comments on the various issues that came up when developing Shadows of the Damned.

At the beginning of 2021, the rights for Shadows of the Damned reverted back to Grasshopper Manufacture, and it was subsequently de-listed from all online stores.

In June of 2023, as it was teased in Travis Strikes Again, a remaster of the game was announced through the ritual sacrifice of James Mountain.

The game would be ported by Engine Software, responsible for the PC ports of killer7 and the first two No More Heroes games, and at the time it was said that it would “probably” be available on every modern platform.

March of 2024 saw the release of a new trailer for the port, now dubbed “Hella Remastered”, and during PAX East, taking place in the same month, it was confirmed that the game would be released on PlayStation 4 and 5, Xbox One, Series S and Series X, Nintendo Switch and Personal Computers.

One final trailer, released in July of that same year, revealed the remaster’s release date, Halloween of 2024. It also detailed the remaster’s new features, namely four new costumes for Garcia, a new game plus option and, of course, support for higher resolutions.

Garcia’s new dussles. The last two are based on Travis Strikes Again and Kurayami Dance respectively.

Interestingly enough, no mention is made of the original director, Massimo Guarini, nor of the original composer, Akira Yamaoka, in either the promotional material for the game or its official website; as both had left the company by this point, it’s likely due to some conflict of interest.