While the moniker itself would not appear until The Silver Case, Moonlight Syndrome already contains many of the themes and motifs that would later be expanded upon in Suda’s extended catalog. In this instance, “Kill the Past” refers to the town itself, going through the process of renovation in order to distance itself from its ritualistic history.

It could also refer to Ryo and Sumio, both crushed by the death of their loved Kyoko: Sumio himself becomes a womanizer, collecting girls which he describes as “specimens” trying to recreate a Kyoko for himself, which ultimately leads to his death at the hands of a disgruntled lover. Ryo, instead, finds the strength within himself to overcome his weakness and become the caretaker / protector he couldn’t be for Kyoko by standing up for Mika, ultimately confronting his past and moving on from her death. However, the ultimate revelation of Mika’s dead body makes it so the object of obsession is merely shifted.

Remnant Psyches

Suda’s interpretation of ghosts, more chaotic and brutal compared to the romanticized depiction of Twilight Syndrome. The term itself (残留思念) has been translated as “lingering consciousness”, “residual thought”, “remaining thought” or “remnant psyche” through the course of the Kill the Past series, but in the original Japanese script, the term was always the same. (Special thanks to political agitator Jolovey.)

While it is never spelled out in Moonlight Syndrome itself, the pulse emanating from Hinashiro high-school and the apartment complexes in 浮誘 FUYOU is described as a “dark thought” with similar terminology; moreover, the 残留思念 spelling was used in the Hyper Playstation article promoting the game, which in itself was probably based on an earlier draft for the story (Ryo’s background as working in a bike repair shop is never brought up in-game, though it is mentioned in the novelization and in the game’s proposal draft), meaning Suda already conceptualized this idea during the development of Moonlight, although it would not make its formal debut until the next game.

During エピローグ EPILOGUE, Chisato has an apropos of nothing speech about how the insanity of man has taken root in the school, said insanity being the “dark thought” mentioned earlier. Renovating the school has done nothing to assuage the “residual thoughts” of the victims of the town’s sacrifice, and as she puts it, tears (of grief) wash away the blood (of death) and the cycle begins anew, moving on without end.

Urbanization

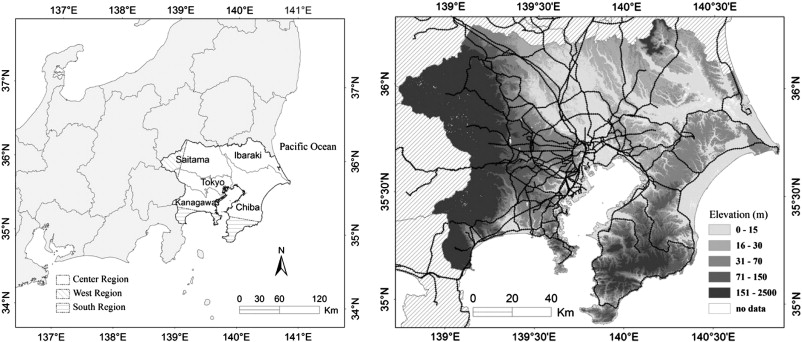

Post-boom urbanization, which in itself is a consequence of the post-WW2 adoption of western capitalism, is generally depicted in Suda’s work as the severing of the thread of tradition for Japan.

Suda himself, being born in the 60s, would have grown up witnessing the urban expansion of Tokyo directly; moreover, he moved to the city quite early in his life due to his young marriage and wanting to distance himself from his birth family. In Moonlight Syndrome, the fictional town of Hinashiro (located in the Musashino district, which would later be revealed in TSC as having been renovated into the 24th special ward of Tokyo) is in the middle of urban development, to the point where new buildings have been popping up between 1996 and 1997, with the demolition of the northern school building and its renovation being the imagery on which the game opens.

The game’s statement, as voiced by Aramata, seems to be that the renovation of the town (purportedly for the reason of distancing it from its past of ritualistic murder) is as useful as giving a coat of paint to a collapsing building; the madness that has seeped into its soil is very much alive, as demonstrated by the fact that, despite changing its look, the town has inexplicably reverted back to its ancestral name of 雛代, a fact that goes unacknowledged by the characters in the story. The town’s appearance of normalcy is only held together by collective delusion.

Hinashiro’s urbanization has also given birth to a new kind of insanity, which we can see hints of in プロローグ PROLOGUE, with Mika’s neighbor coldly dismissing her, and her mother being unaware of what goes on in her own condominium. However, it is mostly dealt with in 浮誘 FUYOU, where middle-schoolers jump to their death from the roof of the apartment complex: apartment-living, which in itself was made necessary by the adoption of salary man lifestyle, despite having brought everyone closer together, it resulted in familial and generational atomization. The middle-schoolers, having both their parents leave the household through the day, have no semblance of a family life, and they cannot socialize with either elementary-schoolers or high-schoolers since they only bond within their age group. Left with no other option, the middle-schoolers choose to jump, driven by the pulse of the condominium (its “dark thought”), in order to protest against their living condition. Some degree of generational divide was already shown in the Kishii’s household, but 浮誘 FUYOU shows us that due to the rapid advancement of technology and society, a difference of just a few years can result in an insurmountable language barrier.

Paradise

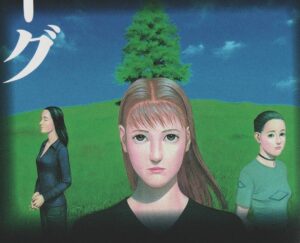

The vision of Paradise depicted in Moonlight Syndrome is “the edge of the world”. We are first presented to this landscape, a lonely tree standing in a grassy field, in 夢題 MOWDEI, where Ryo has an encounter with Rumi, Kyoko and Sumio after being absorbed by Yayoi. Sumio and Kyoko are already dead at this point; While we see her “absorb” Ryo and Sumio directly, and we know that Yayoi was involved in Kyoko’s death (thus we can surmise that she would have absorbed her soul at that time), the presence of Rumi, who just like Ryo is shown as walking around in the living world, is conspicuous and seems to imply that she would have entered a contract with Yayoi’s master, Mithra.

Ryo is once again transported to the edge of the world in 開扉 KAIBYO after being confronted with the reality of Mika’s sexual relations with Sumio. We don’t see the field this time, just his comatose body as he is forced to watch them. When Mika is taken by Mithra he ultimately follows her, only to return in エピローグ EPILOGUE, where he reveals to Rumi that they were together, once more, at the edge of the world.

The field itself is based on a memory that Rumi cherished, when the two couples could co-exist peacefully without any worries.

Ryo dismisses her, claiming that those memories are meaningless; however, it is ultimately revealed in 陰約 INYAKU that he too cherishes those days, as it is a picture of the time they spent together that calms him down from his night terrors. In the In-depth Guide Q&A, Suda describes the edge of the world as a “memory that becomes a place”, the most primitive one, while Sumio calls it a place in which all daily worries melt away and Ryo himself describes it as a place where nothing but tranquility lies.

The game contains many musings on the idea of running away from reality; Ryo himself chastises Rumi as latching onto memories (the same memories that would become the edge of the world) only because she cannot find value in reality. In エピローグ EPILOGUE, Ryo himself decides to accept reality and confront Mithra, which in itself might be considered the power of delusion, in order to save Mika and avenge the ones that had to die for him to get to that point.

In other words, Paradise is depicted as a place separate from reality, a thought that becomes a location to which the characters escape to when they lack the strength to confront the world around them; a return to the past for those unable to kill it. Unfortunately, despite his proclamations, the reveal of Mika’s dead body ultimately sends Ryo’s soul to the edge of the world once more, his body laying comatose when Rumi finds him in reality.

The Moon

The moon itself is going to make an appearance in every single KTP game; said use of imagery originated in Moonlight Syndrome, where the full moon shows up multiple times through the events of the game and closes each chapter along with a term relating to the events that just transpired.

(The voice itself is automated, a detail that would be reprised in all following titles.)

In Moonlight Syndrome, the moon is associated with Mithra, the god of contract, and his silver hair; However, by studying the Zoroastrian mythology that informed the game’s scenario, it is revealed that Mithra is generally associated with the rising sun instead, meaning that he is actually being associated with the moonlight (sunlight reflected on the moon) rather than the satellite itself, a motif which is verbalized in 陰約 INYAKU, where Sumio describes Mithra as “the light of the moon”. In that sense, the title of the game might also mean “Mithra’s Syndrome”.

Divinity

The Kill the Past series features many entities that exist beyond the scope of human perception; in this game they were specifically based on Zoroastrian mythology, with the God of contract Mithra taking center stage. One image which will reoccur through the series is that of God existing beyond the game itself, represented here by showing Mithra in front of the Playstation console in 浮誘 FUYOU. In エピローグ EPILOGUE, when he is challenged by Ryo, he starts breaking the fourth wall by enumerating RPG genre staples

This piece of imagery is likely meant to imply that the existence of Mithra is above that of the cast of Moonlight Syndrome who, as opposed to him, exists “within the game”, which also ties into the following section about interactivity.

Pseudo-Interactivity

Moonlight Syndrome received some backlash due to the lack of investigative elements: The game features no bad endings, there is no way to change the outcome of the story and the various dialogue branches present in the game ultimately lead to the same results.

While this was seen as a downgrade or a lackluster part of the game, I err on the side of seeing this change as intentional: In the In-depth Guide, Suda refers to the game specifically as being pseudo-interactive, meaning that giving the illusion of interactivity to the player while setting them up on a pre-determined path was a conscious design decision, going as far as to mention that in one of the cut scenarios, the impotence of one of the characters in stopping the events that would have taken place would have served to mirror said “pseudo-interactivity”.

Moreover, through the course of the game, several characters are often forewarned of their impending doom ahead of time, yet we as players are powerful to stop it. This was likely meant as a response to the level of interactivity present in Twilight Syndrome, which had to be accommodated for by giving the player an unreasonable amount of influence over the lives of those around them; I tend to believe that Suda’s use of pseudo-interactivity, much like his depiction of the divine as existing beyond the game, is a deliberate tool he uses to properly simulate the experience of existing within the world he created, one where the player character is not omnipotent.