Program: Hoshino, Yuki | Sound: Niikura, Kouji | Screenplay: Suda, Goichi

Moonlight Syndrome could be considered the origin point of the Kill The Past storyline; While the moniker itself would not appear until The Silver Case, Moonlight would introduce many of the over-arching themes and motifs found in later games for the very first time. It is also, however, a direct sequel to the original Twilight Syndrome duology (Tansaku-hen / Search chapter and Kyuumei-hen / Investigation chapter). In other words, the game expects you to be familiar with certain concepts from the TS games, namely the town of Hinashiro and the main trio of Yukari Hasegawa, Chisato Itsushima and Mika Kishii.

For that reason I would wholeheartedly recommend playing them or at least watching them (the translations have been linked in the Syndrome Trilogy translations page) before delving into Moonlight. I don’t plan on covering them in any specific detail since their narratives are pretty linear and self explanatory.

The game opens on the demolition of the Hinashiro school northern building intercut with flashes of the school from olden times, which was also shown in the introduction to Twilight Syndrome.

On some level, Moonlight exists as a rejection of the themes of the original Twilight; in that sense, the demolition of the northern building acts as an allegory of said rejection or as a “goodbye” to the world of Twilight, with the music playing through the scene being “Rainy”, which was prominently featured in the second rumor of the previous game, “MF in the Music Room”.

This also introduces us to one of the game’s main themes, urbanization and the clash between modern (in some ways westernized) values and the Japan of old.

The constant renovation of Hinashiro seems to have the purpose of erasing the town’s past: In Hinashiro Grove, the fifth rumor of the original Twilight Syndrome, we found out that the town actually had a history of ritual sacrifice. The original spelling of its name, 雛代, translates to “Hina Substitute”, with ‘Hina’ referring to Hina Dolls that are used in (among other things) the Japanese ritual of Hina-nagashi. Hinashiro got its name for being an area down-river where numerous ‘Hina Substitutes’ would arrive.

However, through the course of Hinashiro Grove, it is revealed that, at some point, the practice changed from sending paper dolls down the river, to throwing young girls in as a ritual sacrifice to protect the town (hence, the ‘Hina Substitutes’ could also refer to humans). The practice was continued until at least the 60s, with the chapter itself revolving around the spirit of one of the final sacrifices, a young girl named Sakura Himegami, kidnapping Mika Kishii and bringing her to the titular Hinashiro Grove in order to be friends with her and ease her (and the other sacrificed girls’) loneliness. However, Mika was ultimately rescued by her friends Yukari and Chisato by convincing Sakura that by trapping Mika she’d be inflicting on her the same injustice she suffered. At some point between the 60s and the 90s, the town’s name was changed to 雛城, likely in an effort to distance it from its dark sacrificial past, and the northern school building that we see in the flashes was rebuilt into the one that we see being demolished now. However, the game’s ultimate statement seems to be that trying to hide the town’s history is as useful as applying a new coat of paint to a collapsing building: In Occult Mistery Tour, the ninth rumor in Twilight Syndrome, the northern building is still shown as a hotspot for malicious spirits. (It should be noted that both Hinashiro Grove and Occult Mistery Tour were written under Suda’s direction, rather than being pre-existing scenarios inherited from Kimura.) Moreover, in Moonlight Syndrome the town’s name has reverted to its 雛代 spelling without any textual motivation, indicating that the town’s sacrificial roots are very much alive. (Thanks to Jolovey for clarifying these points.)

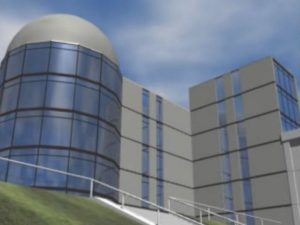

This implication is made even more evident when the sequence ends showing the new northern building, focusing specifically on the newly-built dome area on the 5th floor which is later going to be revealed as the base of operations for the new headmaster’s perverse hobby in 慟悪 DOWAKU. (Both the In-depth Guide and an optional conversation in 夢題 MOWDEI confirm the headmaster was the one who spearheaded the renovations.)

The students of the school will eventually become “sacrifices” for the headmaster’s “artwork”, indicating that it was not evil gods demanding the girls be sacrificed, but the madness of man itself. The word substitute (代) will reoccur several times through the game, especially during 夢題 MOWDEI.

In the next scene, Mika Kishii is walking home at night, returning from a party that Kazuki invited her to, as shadowy figure is shown stalking her. Mika actually complains about having to go to said party as if it were a formal obligation; While vague, this immediately introduces us to Mika’s inner conflict through the course of Moonlight, her own self-loathing in having to partake in popular activities due to peer pressure. She is then alerted to the footsteps following behind her; the player has a few choices at this point, but most of them will eventually lead to a confrontation with what appears to be a cultist who, if given the chance, will start rambling about an incoming catastrophe that Mika could only avoid by joining his group. (If you elect to run away from him, Mika will wonder if he was a part of the Kishii fan club from Twilight Syndrome.)

This is actually referring to a real societal problem in 80s and 90s Japan, the rise of several cult religions which mostly sought to take advantage of their followers during the post-bubble urbanization wave and subsequent recession, with its lack of classical spirituality. This eventually led to the rise of the Aum Shinrikyo cult and its two Sarin gas attacks in 1994 and 1995, just two years before the release of Moonlight Syndrome. Similar themes have been brought up in pop media in the videogame Yakuza 0 and in the manga 20th Century Boys (later adapted into a movie trilogy), both sporting direct parodies of cult leader Shoko Asahara.

The novel series and anime show Monogatari deals with Senjyogahara’s mother joining a cult as part of that character’s backstory.

The filmography of director Hirokazu Koreeda also deals with the rise of Japan-based cults, most importantly in the movie “Distance” from 2001, dealing with those people who were left behind by their relatives who joined a cult (again, specifically modelled after Aum Shinrikyo).

All this to say that the rise of Japan-based cults was a real issue that was very much felt by people who grew up during that era of “modernization”, such as Suda Goichi. Killer7 itself contains at least one direct reference to Aum Shinrikyo.

I also have reason to believe that the old man might be another manifestation of Mithra, the white haired boy who will torment Mika through the course of the game. While the old man never appears again, his voice is heard at several key points in the game, taunting Mika much like Mithra would. If you try to confront the cultist he will disappear into thin air, which hints at something supernatural going on with him. Moreover, if you avoid encountering him altogether, his disembodied voice will taunt Mika saying that “they” will be watching her. In his Killer7 appearance, Mithra speaks in a double voice, one of which is that of an old man, which makes me think the “we” he is talking about is just multiple manifestations of Mithra.

After dealing with the cultist (one way or another), Mika is chased by a disembodied child-like laugh all the way to her apartment complex. The laugh is revealed as originating from the white haired boy Mithra and the scene closes on a shot of the full moon, immediately followed by a camera lens closing down.

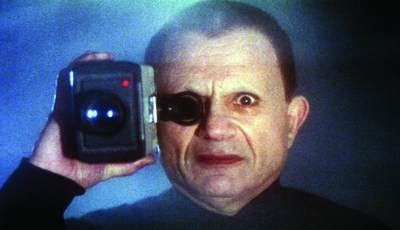

This is actually very important because Mithra is shown operating a camera in the attract mode video. Implying that Mithra has already “set his sights” on Mika, so to speak.

There is a non-zero chance that Moonlight Syndrome might have been partially inspired by the David Lynch movie “Lost Highway”, which happens to star a mistery man operating a camera in a very similar way to Mithra in that shot.

The night club in Moonlight Syndrome also happens to be called “Lost Highway”, which further hints at the thematic connection between the two. In the language of Lost Highway, the Mistery Man is an outside observer whose aim seems to be to awaken the homicidal instincts of main character Fred Madison. (Obviously there’s a lot more going on in Lost Highway but this isn’t the place for a full breakdown.)

Mithra has a similar role in the events of Moonlight Syndrome, in that instead of directly tormenting the main characters, he mostly just takes advantage of their own inner desires (Which are the words shown next to them in the attract mode video) to pit them against one another and ruin their lives for his own amusement. Which is why Suda referred to the game as psychological horror, rather than supernatural horror. (Source 1, Source 2.)

Mithra himself might have shot the introductory video, which is likely playing on the old tv shown in the title screen.

While Suda has never confirmed the Lost Highway connection (although the Flower, Sun and Rain Official Fanbook does contain one direct reference to the movie), we can connect his depiction of Mithra to the canon of David Lynch thanks to the Suda51 Official Complete Book, in which he cites Killer Bob from Twin Peaks as a direct inspiration, namely the fact that Mithra, as an unseen evil, indirectly torments the characters by lurking in the darkness.

Before entering her apartment building, Mika is reintroduced to Aramata. Aramata was a minor character in the Twilight Syndrome games, a journalist dealing with occult magazines who happened to be acquainted with Mika and helped with the main trio’s investigations during the first two games. He only spoke with Mika through the phone in Twilight Syndrome, making this his physical debut. Hence why Mika does not recognize him initially.

For some cultural context, the occult magazines (such as Mu) that Aramata would be dealing with were an actual fad / subculture in Japan, and they are parodied in a variety of other games like the Castlevania series or Metal Gear Solid. A similar type of magazine would even appear in a subsequent GHM game, The 25th Ward. Said magazines often deal with things such as UMAs and alien invaders other than the occult.

The Kōji Shiraishi 2005 film “Noroi” also delves into that subculture quite extensively, going as far as to shoot fake reality shows on the subject.

Mika’s commenting on the fact that Aramata seems to be out of a job is also a cultural remnant from the post-bubble urbanization wave (and subsequent recession) of the 90s, considering how the belief in the supernatural was waning at the time (which is specifically the reason why occult magazines transitioned into more “sci-fi” subjects, such as UMAs and space aliens).

Aramata’s rant seems to get at the fact that, in his view, the air of normalcy presented by suburban society is nothing but a smokescreen or a collective delusion, which is further hinted at by the fact that Mika describes her neighborhood as “perfectly normal” despite being chased around by a ghostly laugh just a few minutes before. In other words, the “everyday life” of urbanized Hinashiro is merely a lie that is reinforced by the media, the police force and the collective unwillingness to face the truth by the general population, a verbalization of the theme that was expressed visually at the beginning of the chapter.

Aramata then reveals that he has come to Hinashiro in person after realizing that Mika’s school, the town and possibly Mika herself must represent some sort of hotspot for the supernatural. By recapping the events of the first two games (the supernatural incidents that Mika, Chisato and Yukari were involved in), Mika is finally convinced that there has to be some truth to the words of Aramata. It seems that somehow she never gave much thought to how utterly bizzarre it would be for high-school girls such as Mika and her friends to be constantly involved in supernatural incidents, again hinting at the theme of collective delusion. By being a part of such a weird town, Mika just accepted its events as her own reality, lacking the clarity of an outside observer.

FUN FACT: Mika insulting Aramata over his verbosity might be an inside joke about how endless his explanations would come off as in the original Twilight Syndrome. Hiroshi Kasai, the main writer of Twilight, commented on this himself in his memorandum.

As if shook from a deep sleep, Mika suddenly realizes how even her prior meeting with the cultist shouldn’t be considered a normal occurrence either; Aramata then confesses that he actually witnessed the encounter. When chastised by Mika for not helping her, however, he responds that he is merely a stranger to the town, and it is not up to him to solve its mysteries, a role that he entrusts to Mika instead.

He ultimately resolves to help Mika by acting as the game’s save point, recording her progress in accordance to his role as a journalist.

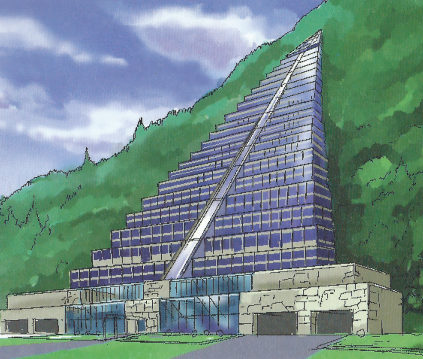

Mika then takes the elevator to her apartment. It should be noted that her condominium is shaped like a pyramid or a ziggurat and it is later referred to as the “Pyramid condo”.

According to Suda himself, the mythology of Moonlight Syndrome is based on Zoroastrianism (Source), the biggest hint towards that being the presence of the god Mithra. However, the pyramid is not a symbol generally associated with Zoroastrianism. The most famous usage of pyramids as religious symbols comes from the ancient Egyptians who, according to some historians, viewed them as a point of connection between the world of the living and that of the dead. (Pyramids were built on the western side of the river Nile, which is associated with the setting sun and the world of the dead in Egyptian mythology. That is to say that they might have been meant to accompany the soul of the living god Pharao to the afterlife.)

South american pyramids were also used to bury divine kings, and in some occasions for ritualistic human sacrifices.

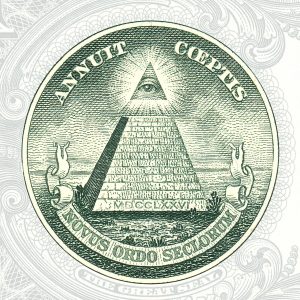

Meanwhile, in modern times, the pyramid has been mostly used as a symbol of top-down control, be it political, religious or economical. (Think of the pyramid symbol on the american dollar, which in itself ties back to its Egyptian meaning through its roots in freemasonry, whose ideology is at least partially rooted in Egyptian mythology.)

Mika’s condominium might be foreshadowing her ultimate fate of being a living sacrifice for the amusement of the gods, much like the Hinashiro maidens of old by which she was nearly imprisoned. It might also be hinting at the technocratic powers asserting their dominance over a once traditional Japan, represented by the town’s renovation.

Mika arrives home, but she passes out from exhaustion before being able to eat dinner with her family. In the middle of the night, she is awoken by a phone call from what is implied to be a lover, who invites her to the park in order to discuss something important. We can infer from his tone and choice of words that he is quite a manipulative person, playing to Mika’s ego in order to convince her.

As she is walking under the full moon to go meet her boyfriend Sumio, Mika’s path crosses with that of Ryo. Mika regards Ryo with suspicion, while Ryo comments on how much Mika resembles his sister Kyoko. Mika then shows her affection and fascination towards Sumio, who silently stares at her with a blank expression.

We’ll eventually find out in 夢題 MOWDEI that Sumio had been forewarning others of his impending death; While it is unconfirmed, we could surmise that might have been the content of his unseen conversation with Mika. Ryo walking away from their meeting place seems to imply the two of them also shared some words before Mika arrived, however, this is never brought up again.

The next morning, Mika’s classmates Miho, Miki and Kazuki are in their classroom discussing an accident which supposedly took place the previous night, when Mika was meeting up with Sumio, on the mountain road Reigetsu Pass. The victim of the accident was Kyoko Kazan, Ryo’s sister, an ex-student of Hinashiro high-school who happened to be two years above Mika. (In other words Kyoko would have been in her third year of high school at 17/18 years of age, while Mika and her classmates would have been in their first year at 15/16. For reference, Mika is a second year student in this game, with Yukari and Chisato being her upperclassmen in the third year.)

Mika has no memory of Kyoko at all, although her classmates insist that the two of them were as similar as twins, and that they used to discuss this factoid quite often. (During the final chapter of Twilight Syndrome, The Otherside Town, Mika even mentions that meeting your doppelganger is an omen of impending death, which makes her forgetfulness even weirder considering Kyoko would have still been in school at the time.) Supposedly, she crashed into a truck on her motorcycle and her body was blown to bits, but Mika has no knowledge of this event either. In fact, she seems quite reluctant to discuss it, despite the fact that in Twilight Syndrome she was often the engine driving the supernatural investigations due to her morbid curiosity.

The death of Kyoko actually cannot be placed chronologically in any logical fashion within the game’s timeline. It will actually be reported on several different times, all of which contradict each other. I will elaborate more on this in 夢題 MOWDEI.

Miho begins taunting Mika, claiming that without the influence of her friend Yukari (the main protagonist of the Twilight Syndrome games, and the one who Mika would often rope into her investigations) her personality fails to stand out. An argument erupts between the two about Mika’s reluctance to cover the subject, with Miho framing it as hypocritical of Mika to be so judgmental of a behavior she herself used to engage in. (It should be noted that Miho was actually a minor character in Twilight Syndrome, who would occasionally join Mika in her gossiping.) The argument is eventually broken off by Miki and Kazuki, and Miki and Miho leave the classroom.

The two of them left alone, Kazuki asks Mika if she was aware that Rumi Tohba’s older brother was dating Kyoko. Mika responds with silence, and Kazuki comments that she suddenly turned pale. Rumi Tohba’s older brother is, in fact, Sumio Tohba, the man that Mika sneaked out of her house to meet the night before, meaning her sudden reaction was one of jealousy, having just found out that the man she considered to be her boyfriend was seeing at least one other woman. Mika then infers about the whereabouts of Rumi, to which she is told that she hasn’t come in to school that day.

After class, Mika and Kazuki meet up again in the corridor, where they discuss the argument she had with Miho in the morning. Kazuki suggests Mika to meet up with her senpai Yukari in order to cheer up. However, Mika is reluctant to do so since Chisato and Yukari are getting ready for their third-year exams.

Kazuki then invites Mika to spend the evening with her at the Lost Highway club, where a girl supposedly killed herself the previous night. Just as before, this event cannot be placed chronologically in any sort of timeline, but I will elaborate more when every instance of it has been shown. Mika shows some reluctance, and Kazuki eventually relents.

Mika is once again shown walking home and reflecting the events of the previous night, namely being stalked by the cultist. This is important because it confirms that the events we just witnessed did take place in a chronological sequence, which will be useful to point out the inconsistencies later on. Mika tries to greet her neighbor who walks by without acknowledging her, showing how distant the communal life has become despite everyone being physically closer together since the implementation of apartment-based housing. She then tries to find her house key, which a white haired boy (Mithra) then hands out to her, claiming she had dropped it.

Mika manages to have dinner with her parents this time; her father starts inquiring about Mika’s school life, his sudden interest being sparked by a coworker’s daughter mysteriously going missing. He blames it on the country being turned into a slum by the current recession, and claims that unless his generation takes charge, nothing will change. Mika tells her father not to worry, but the two of them might as well be speaking different languages. Her mother eventually cuts off the conversation as she considers it too morbid for the dinner table.

This is once again an example of social commentary on the changing values of 90s Japan. Before urbanization, it was way more common for children to come from ‘ni-setai’ or ‘san-setai’ houses, meaning that two or three generations of the same clan would share the same household. That trend was already in decline in the 80s and 90s, and it has only gotten more rare since, to the point where it only seems to exist in rural areas at this point (With around 80% of the Japanese population residing in urban areas).

This article from Business Insider published in 2018 claims that from 1985 to 2015, the number of elderly Japanese citizens living alone has increased by 600%. It also states that the generational divide had gotten so bad that Japanese senior citizens would get arrested on purpose to have the state take care of them in their final years.

We can already see that Mika’s life is growing distant if not entirely separate from that of her parents, who having grown up in a world that looks, sounds and behaves differently from her own, have little chance of understanding her. In fact, she never shares any of her worries with her parents (she appears to be more open with Aramata, a stranger, simply because he is more immersed in the occult pop-lore) and they are not aware of her relationship with Sumio, her supernatural investigations or her clubbing habits, which she keeps hidden by sneaking out without their knowledge as shown earlier.

This theme is also a carry-over from Twilight Syndrome, in which we were shown the household of the main protagonist Yukari Hasegawa. While the Kishii household is relatively stable, Yukari’s parents went through a divorce, a practice that was also made a lot more common by dividing families through their office jobs (what is called being a “salary man” in Japan) during the westernization/modernization of Japan’s urban areas. (This problem is by no means exclusive to Japan at all. The paradigm shift of office employment for both parents which went hand in hand with urbanization was instrumental in the destruction of the nuclear family as it had existed until that point. You can see an example of it from Italy in the movie “It was the Hand of God” by Paolo Sorrentino off the top of my head.)

Yukari finds her household situation frustrating specifically because her mother doesn’t seem to be interested in Yukari as a person at all, preferring instead to make up an imaginary daughter based on what news media would tell her about “the youth”. Which is not dissimilar to Mika’s father suddenly gaining an interest in her daughter’s activities, only when it became a subject of gossip at his workplace.

Yukari’s need for relief is what eventually brought her closer to Mika during the events of Twilight Syndrome; While she initially found Mika to be obnoxious, she would still take her company over that of her own mother, and while the pairing might have initially been forceful it eventually blossomed in a strong friendship between the two of them and Chisato.

Mika then asks about the kid she met in the corridor, but her parents only offer vague answers as per who it might have been. Their conversation is suddenly interrupted by a live report of an accident at Reigetsu Pass, where Kyoko Kazan (who Mika’s father initially mistook for his own daughter) crashed her motorcycle into a truck, causing several injuries in the process.